You’re sitting at a family dinner, and someone mentions that Great-Aunt Martha had a "bad leg" or that your cousin just got put on blood thinners after a long flight. It’s one of those moments where you start wondering if your own DNA is a ticking clock. Are blood clots hereditary? It’s a question doctors hear constantly, and the answer isn't a simple yes or no, but a "kinda—and it depends on which genes you're carrying."

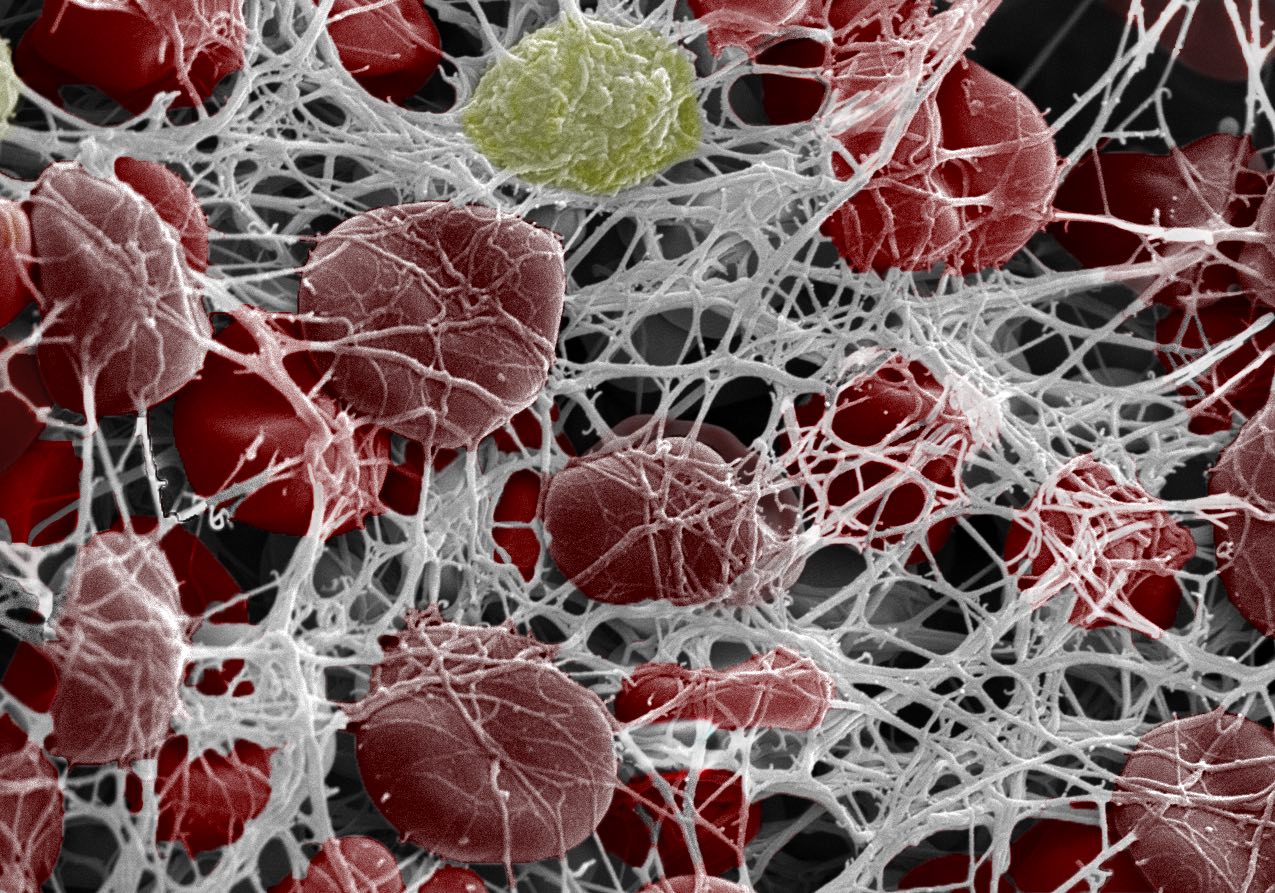

Blood clots are actually a life-saving mechanism when you cut your finger. But when they form inside a vein (Venous Thromboembolism or VTE), they become a silent, sometimes deadly problem.

Genetics play a massive role.

Some people are born with a blood chemistry that’s basically "stickier" than others. If you’ve ever felt like your family has a history of "thick blood," you’re probably talking about thrombophilia. This isn't just one condition; it's a whole bucket of genetic quirks that can make you significantly more likely to develop a Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) or a Pulmonary Embolism (PE).

The Genetic "Glitch" Called Factor V Leiden

If we're talking about inherited risks, we have to start with Factor V Leiden. It sounds like a character from a spy novel, but it’s actually the most common inherited blood clotting disorder in the United States and Europe.

Most people have a protein called Factor V that helps blood clot. Normally, another protein called Activated Protein C (APC) comes along and shuts Factor V down so you don't clot too much. But with the Leiden mutation, the Factor V protein is shaped a little weirdly. APC can't "grab" it to turn it off.

The result? The clotting process stays active longer than it should.

Roughly 3% to 8% of people with European ancestry carry one copy of this mutation. If you only have one copy (heterozygous), your risk of a clot is maybe 5 to 7 times higher than the average person. That sounds scary, but honestly, most people with one copy never actually get a clot. They live their whole lives totally unaware of their "glitch" until a major event like surgery or pregnancy triggers something.

Now, if you inherit a copy from both parents (homozygous), the risk skyrockets to about 80 times higher. That's a different conversation entirely.

✨ Don't miss: Fruits that are good to lose weight: What you’re actually missing

Prothrombin G20210A: The Volume Knob Mutation

Then there’s the Prothrombin G20210A mutation. This one is less about the shape of the protein and more about the amount.

Prothrombin is a protein your body uses to create thrombin, the "glue" that makes a clot. If you have this mutation, your body simply makes too much prothrombin. Think of it like a faucet that's always dripping slightly. Over time, that extra protein builds up, making a clot much more likely. It affects about 2% of the Caucasian population and is less common in other ethnic groups.

It's subtle. You won't feel it. You won't have symptoms. But it’s lurking there in the background, especially if you’re also dealing with other risk factors like smoking or hormonal birth control.

The Rare but Serious Deficiencies

While Factor V and Prothrombin mutations are the "common" ones, there are some rarer genetic issues that are much more aggressive. These involve deficiencies in natural anticoagulants—the body's built-in "blood thinners."

- Antithrombin Deficiency: This is the big one. It’s rare, affecting maybe 1 in 2,000 people, but it’s powerful. People with this deficiency have a very high lifetime risk of VTE.

- Protein C and Protein S Deficiencies: These proteins are like the brakes on a car. If you don't have enough of them, the clotting "engine" just keeps revving.

If you see a family pattern where people are getting clots in their 20s or 30s, or having multiple miscarriages, doctors often look for these specific deficiencies first. They are heavy hitters in the world of hematology.

Why Genetics Isn't the Whole Story

Here’s the thing: DNA is the loaded gun, but lifestyle is often the trigger.

You could have Factor V Leiden and never get a clot if you stay active, keep a healthy weight, and avoid smoking. Conversely, someone with "perfect" genes can get a massive blood clot after sitting on a 15-hour flight to Sydney without moving their legs.

It’s about the "second hit."

🔗 Read more: Resistance Bands Workout: Why Your Gym Memberships Are Feeling Extra Expensive Lately

Medical researchers often talk about the Multi-Hit Hypothesis. You might have one "hit" from your parents (your genetics). But you usually need a second hit—like a major surgery, an injury, or a long period of immobility—to actually cause a DVT. This is why doctors get so picky about checking your family history before prescribing estrogen-based birth control. Estrogen is a "hit." If you already have a genetic "hit," adding estrogen can push your risk over the edge.

The Mystery of Blood Type

Did you know your blood type is a hereditary factor for clots? It’s true.

People with Type O blood actually have the lowest risk of VTE. If you have Type A, B, or AB, your risk is slightly higher. Why? Because people with non-O blood types have higher levels of von Willebrand factor and Factor VIII—two things that help blood stick together.

It’s a small difference, but in the grand scheme of "are blood clots hereditary," it’s another piece of the puzzle you inherited from your parents.

When Should You Actually Get Tested?

Testing your DNA for clotting disorders isn't like getting a cholesterol check. You don't just do it for fun.

Hematologists (blood doctors) are actually quite conservative about genetic testing. If you’ve never had a clot, even if your mom had one at age 60, they might tell you NOT to get tested. Why? Because it can affect your ability to get life insurance or disability insurance, and the "treatment" for a genetic mutation is often just... being careful.

However, testing is usually recommended if:

- You had a clot before age 50 without an obvious cause.

- You’ve had recurring clots.

- You’ve had clots in weird places (like the veins in your abdomen or brain).

- You have a very strong family history (multiple first-degree relatives with clots).

- You have a history of multiple unexplained miscarriages.

Understanding the Risks Beyond the Genes

We talk so much about DNA that we forget about the stuff we "inherit" that isn't in our chromosomes—like family habits.

💡 You might also like: Core Fitness Adjustable Dumbbell Weight Set: Why These Specific Weights Are Still Topping the Charts

If your family loves salty food, struggles with obesity, or everyone smokes, you might think the blood clots are "hereditary" when they’re actually a result of the environment you grew up in. Obesity, in particular, creates chronic inflammation that makes blood more prone to clotting.

Also, look at your family's history of autoimmune issues. Something called Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) can run in families and is a major cause of clots. It's not exactly a "clotting gene," but it's an immune system "glitch" that leads to the same dangerous result.

Real-World Nuance: The Race and Ancestry Gap

Most of the early research into "clotting genes" focused on people of European descent. This has created a bit of a blind spot in medicine.

For instance, Factor V Leiden is almost non-existent in people of African or Asian descent. Yet, African Americans actually have the highest overall rate of VTE in the United States. This suggests there are other genetic markers or environmental factors we haven't fully mapped out yet.

If you're not of European descent and your doctor says "you don't have the common clotting genes," that doesn't mean you're in the clear. It just means the "standard" tests might not be looking for your specific risk factors.

Actionable Steps: Taking Control of Your Risk

If you're worried about your family history, don't panic. Genetic risk isn't a destiny; it's a heads-up. Here is how you actually handle the "hereditary" aspect of blood clots:

- Map Your Pedigree: Talk to your relatives. Find out specifically who had a clot, how old they were, and what they were doing at the time (e.g., "Uncle Joe got a clot, but he was also in a full leg cast for six weeks"). This context matters immensely to a doctor.

- The "Flight Protocol": If you know you have a family history, never sit still for more than two hours. On long flights or car rides, do ankle pumps, wear compression socks (15-20 mmHg is usually enough for travel), and stay hydrated.

- Hormone Awareness: Before starting HRT (Hormone Replacement Therapy) or the pill, mention your family history. There are progestin-only options or non-hormonal methods that don't spike your clot risk.

- Surgery Prep: If you’re scheduled for surgery, tell the surgeon about your family history. They can give you a preventative dose of a blood thinner (like Lovenox) or use "squeeze boots" (SCDs) during and after the procedure.

- Know the Signs: No matter your genes, know what a DVT feels like. It’s usually one-sided swelling, redness, and a pain that feels like a charley horse that won't go away. If you get sudden shortness of breath or chest pain, that's the "ER now" signal for a potential Pulmonary Embolism.

Blood clots are a complex mix of the code you were born with and the way you move through the world. While you can't swap out your DNA, knowing your hereditary risk gives you the power to prevent the "second hit" that turns a genetic quirk into a medical emergency. Keep the conversation with your family open, keep your legs moving, and don't ignore the swelling.

Next Steps for You:

- Audit your family history: Specifically ask about DVTs, PEs, or unexplained "sudden" deaths in relatives under 50.

- Consult a Hematologist: If you have more than one first-degree relative with a history of VTE, request a consultation to discuss if a "Thrombophilia Panel" is right for you.

- Review medications: If you are on estrogen-containing medications, check with your GP to ensure your risk profile is still acceptable given your family history.