You've probably seen those colorful diagrams in biology textbooks. They look like weird, abstract paintings of beans with tails and squiggly insides. If you're scratching your head wondering are bacteria prokaryotic or eukaryotic, let's just clear the air right now: Bacteria are prokaryotic.

Always.

📖 Related: P Spot Explained: What Most People Actually Get Wrong

There are no exceptions.

But saying they're "prokaryotic" is kinda like saying a car is "mechanical." It tells you the basic blueprint, but it doesn't really explain how the engine actually runs or why it matters to you. Honestly, the distinction between these two cell types is the biggest divide in the history of life on Earth. It's a much bigger deal than the difference between a human and a mushroom.

Why Being Prokaryotic Changes Everything for Bacteria

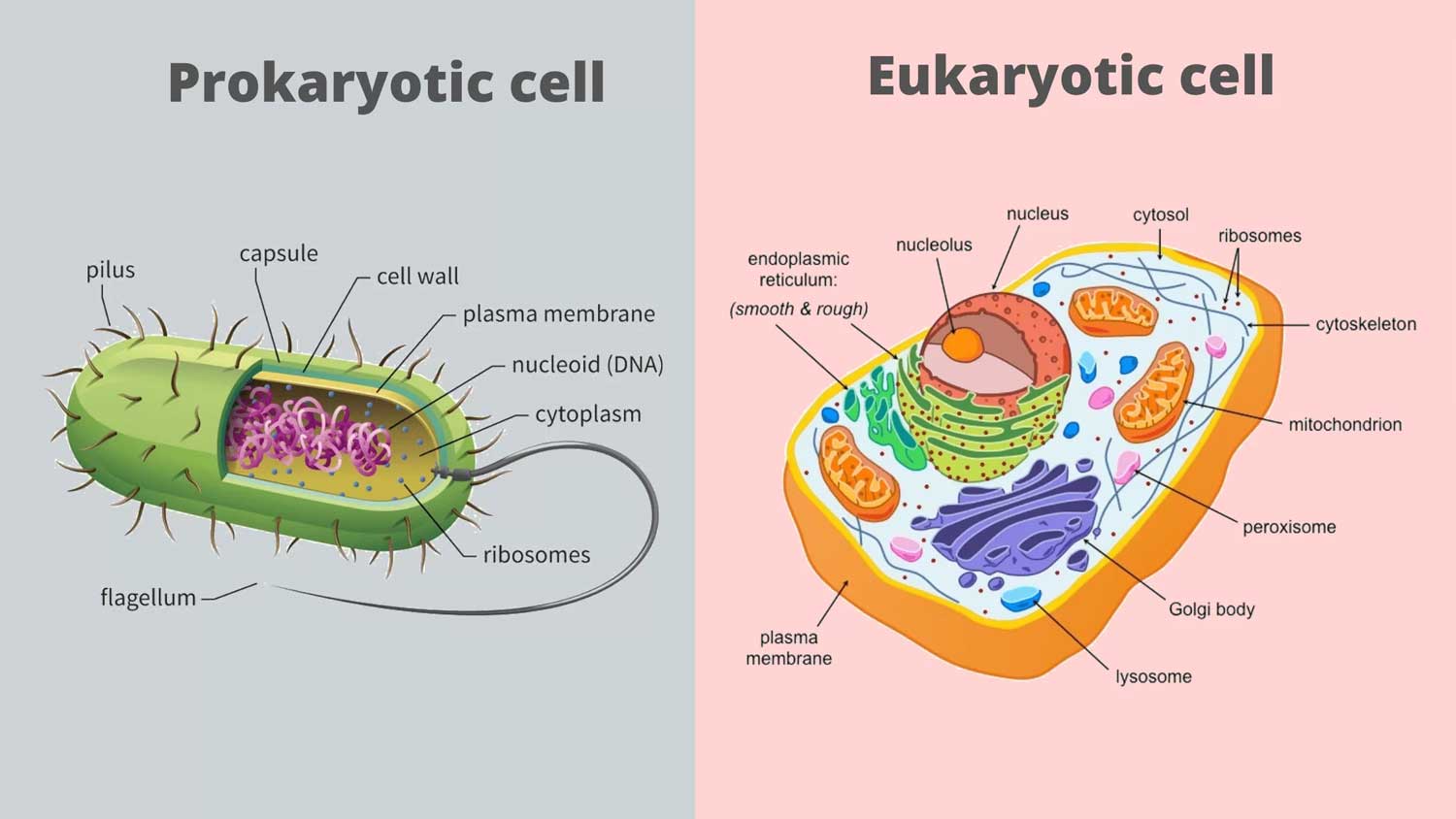

Think of a eukaryotic cell—the kind you have—like a high-end mansion. You’ve got a dedicated kitchen (mitochondria), a library for the blueprints (the nucleus), and a complex shipping department (the Golgi apparatus). It’s organized. It’s expensive to maintain. It’s sophisticated.

Bacteria? They live in a studio apartment.

Everything happens in one room. There is no nucleus. The DNA just floats around in a messy clump called a nucleoid. If a bacterium wants to make energy or copy its genetic code, it does it right there in the open. This lack of "membrane-bound organelles" is the defining trait of being prokaryotic.

The DNA Situation is Actually Wild

In your cells, DNA is wrapped up in neat, linear strands. In bacteria, the DNA is usually a single, messy circle. It’s like the difference between a stack of paper and a rubber band. Because they don't have a nuclear wall getting in the way, bacteria can translate their genetic code into proteins almost instantly.

They are fast. Really fast.

While a human cell might take 24 hours to divide, some bacteria like Escherichia coli can double their population in 20 minutes. This is why a single bacterium on a piece of raw chicken can become millions by the time you're done with your afternoon nap. Their prokaryotic simplicity is their greatest evolutionary weapon.

Where People Get Confused: The "Organelle" Myth

If you read a textbook from twenty years ago, it probably said bacteria have "no internal structure." That’s actually a bit of a lie.

We used to think they were just bags of chemicals. Now, thanks to better microscopy, we know bacteria have a cytoskeleton. They have specialized protein compartments. But—and this is the key—they still fit the definition of are bacteria prokaryotic or eukaryotic because they lack those fancy lipid-wrapped internal rooms.

Take ribosomes, for example. Both types of cells have them because you need ribosomes to make protein. But bacterial ribosomes (70S) are smaller and shaped differently than yours (80S). This tiny, microscopic difference is literally the reason you are alive today.

Why? Because many antibiotics, like tetracycline or erythromycin, are designed to "fit" into the bacterial ribosome but not the human one. They gum up the works of the bacterial factory while leaving your cells untouched. If bacteria weren't prokaryotic, we wouldn't have a way to kill them without killing ourselves.

The Massive Size Gap

Size matters here. Most bacteria are about 1 to 5 micrometers. A typical human cell? Ten to a hundred times bigger.

✨ Don't miss: Images of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs: Why Most Versions You See Are Actually Wrong

Imagine a mouse standing next to a blue whale. That’s the scale difference. Because bacteria are so small, they rely on simple diffusion to move things around. They don't need a complex transport system because the "room" is so tiny that everything is already within reach.

The Weird Exceptions That Prove the Rule

Biology loves to break its own rules. While the answer to are bacteria prokaryotic or eukaryotic is always "prokaryotic," some bacteria try their hardest to look like the other side.

Thiomargarita namibiensis is a giant. It’s a bacterium that can grow to be 0.75 millimeters wide—large enough to see with the naked eye. To survive being that big without being eukaryotic, it has a massive central "bubble" (a vacuole) that pushes its life-sustaining parts against the outer wall.

Then there are the Planctomycetes. These weirdos actually have a membrane around their DNA. For a long time, scientists freaked out, thinking they found a "missing link." But after deeper genetic sequencing, it turns out they are still definitely bacteria. They just have a very fancy way of folding their internal membranes.

Beyond Bacteria: The Third Player

When people ask about prokaryotes, they usually only think of bacteria. But there’s another group called Archaea.

Archaea look like bacteria. They are prokaryotic (no nucleus, circular DNA). But genetically, they are more like you and me. They live in extreme places—boiling hot springs, salt lakes, and deep-sea vents. For a long time, we lumped them in with bacteria, but that was a mistake.

The tree of life has three main branches:

- Bacteria (The classic prokaryotes)

- Archaea (The extreme prokaryotes)

- Eukarya (Everything else: plants, animals, fungi)

So, while all bacteria are prokaryotes, not all prokaryotes are bacteria. It's a bit like saying all Fords are cars, but not all cars are Fords.

✨ Don't miss: What Really Happened With Tylenol: The 2026 Pregnancy and Lawsuit Update

How This Affects Your Health Every Day

This isn't just academic trivia. The prokaryotic nature of bacteria is the foundation of modern medicine and biotechnology.

Since bacteria are prokaryotic, we can "hack" them. We take a piece of human DNA—the instructions for making insulin, for example—and we pop it into a bacterium. Because the bacterium's DNA is just floating around in a simple circle, it’s easy to manipulate. The bacterium reads our instructions and starts pumping out insulin.

Most of the world's insulin supply is made this way. We’ve turned these simple cells into microscopic factories.

On the flip side, their simplicity makes them adaptable. They swap pieces of DNA (called plasmids) like kids trading Pokemon cards. If one bacterium figures out how to survive an antibiotic, it can literally hand that "cheat code" to its neighbor. This is how "superbugs" like MRSA are born. Eukaryotic cells can't really do this. We have to wait for slow, generational evolution. Bacteria just trade secrets and move on.

The Evolutionary Handshake

Here is the most mind-blowing part: you are actually part prokaryote.

Millions of years ago, a large eukaryotic cell basically swallowed a small, aerobic bacterium. Instead of digesting it, the two struck a deal. The bacterium got a safe place to live, and in exchange, it provided energy.

That bacterium eventually became the mitochondria inside your cells today.

This is called the Endosymbiotic Theory. It’s why your mitochondria still have their own circular DNA and their own 70S ribosomes—just like bacteria. When you ask are bacteria prokaryotic or eukaryotic, you’re really asking about the history of your own body’s power plants.

Moving Forward With This Knowledge

Understanding the prokaryotic nature of bacteria helps you make better decisions about your health and the world around you.

- Antibiotic Stewardship: Now you know why antibiotics don't work on viruses (which aren't even cells) and why they target specific bacterial parts. Taking them when you don't need them just gives bacteria more time to trade those "cheat code" plasmids.

- Probiotics: Your gut is a massive ecosystem of prokaryotic life. These cells are vastly different from yours, but they perform chemical reactions your "mansion" cells can't handle.

- Sterilization: Knowing that bacteria are simple doesn't mean they are weak. Many can form "endospores," which are like tiny escape pods that survive boiling water and radiation.

If you're studying for a test or just curious, remember: prokaryotes are the "pro" (before) "karyon" (nucleus). They are the original survivors. They've been here for 3.5 billion years, and honestly, they'll probably be here long after we're gone.

What to do next

If you're looking to apply this practically, start by looking at the labels on your cleaning products or medications. Look for terms like "protein synthesis inhibitor" or "cell wall synthesis inhibitor." These are direct attacks on the specific prokaryotic traits we just discussed. Understanding the "studio apartment" lifestyle of a bacterium makes it much clearer why those treatments work—and why they are so different from treating a fungal infection or a viral one.