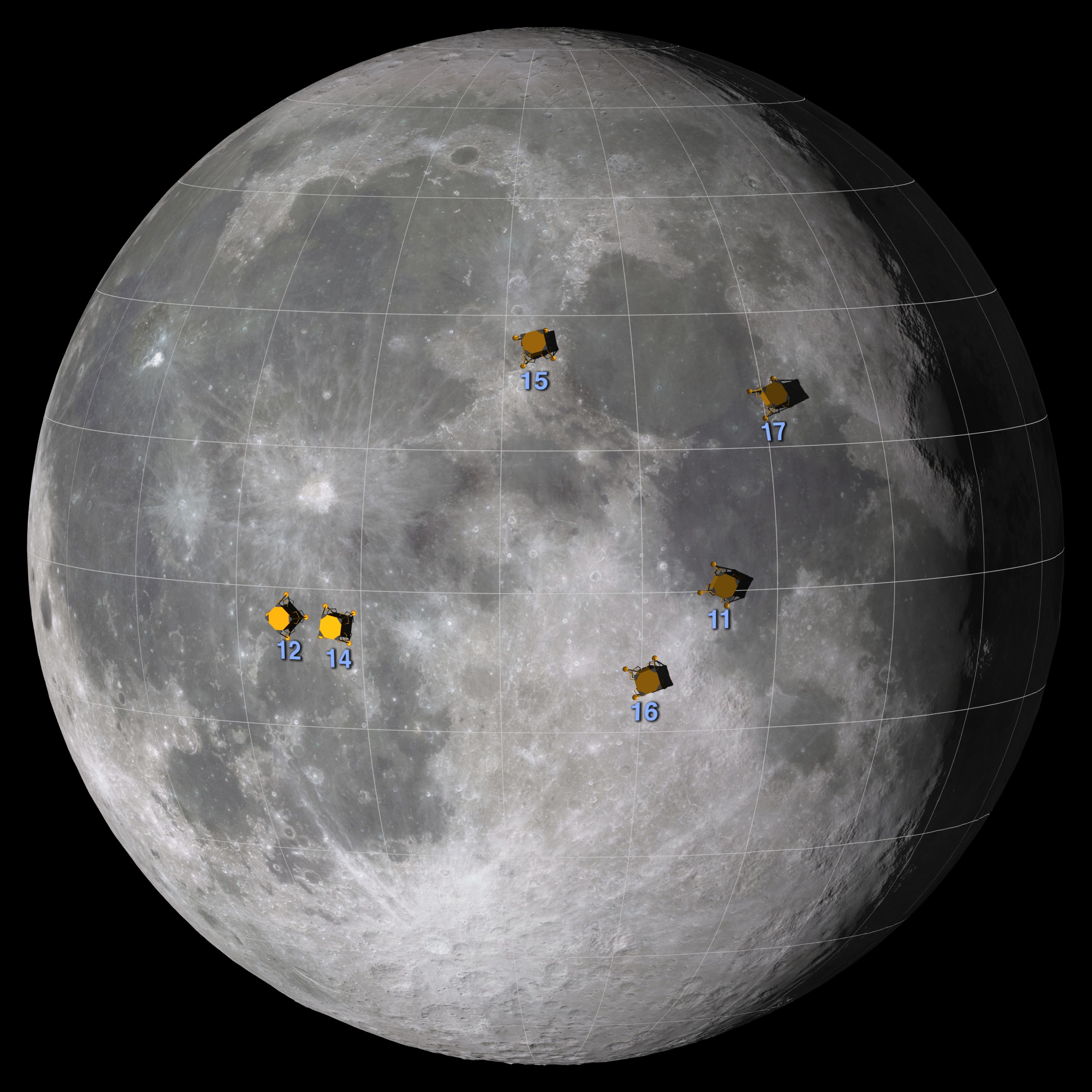

Believe it or not, people still argue about whether we actually went to the Moon. It’s wild. Despite the mountains of data, the rocks brought back, and the thousands of people who worked on the Saturn V, the "hoax" crowd is loud. But here is the thing: we have visual receipts now. When people talk about Apollo landing sites photographed from orbit, they aren't talking about grainy telescope shots from Earth. They’re talking about the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO).

Since 2009, this NASA satellite has been whipping around the Moon at incredible speeds, snapping photos that are sharp enough to make a conspiracy theorist sweat. You can literally see the dual tracks left by the Lunar Roving Vehicle. You can see the dark smudges where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked around the Eagle. It isn't just a dot; it’s a crime scene of human achievement.

Honestly, the scale of these photos is hard to wrap your head around. The Moon is a big, lonely place. When you see the tiny, fragile descent stage of the Lunar Module sitting in the middle of a vast, cratered desert, it hits different. It makes the whole "giant leap" feel a lot more precarious and a lot more real.

The LRO and the End of the "Telescope" Myth

Commonly, people ask why we can't just point the Hubble Space Telescope at the Moon and see the flag. It sounds like a reasonable request. Hubble can see galaxies billions of light-years away, right? So why not a flag on our own doorstep?

Physics is a buzzkill.

Hubble is designed for the massive and the distant. Its resolution is about 0.05 arcseconds. If you pointed it at the Moon, the smallest thing it could see would be roughly the size of a football stadium. The Apollo descent stages are about 4 meters wide. To Hubble, the Apollo 11 site is just a fraction of a single pixel. You wouldn't see a thing.

This is why the LRO changed the game. It’s orbiting as low as 20 to 30 miles above the lunar surface. That is basically a low-altitude flight over a city. Because it’s so close, the Apollo landing sites photographed by its cameras show details down to about 25 centimeters per pixel.

In these images, the Lunar Module descent stages appear as bright squares with distinct shadows. The shadows are actually the giveaway. Depending on the time of the lunar day, those shadows stretch out, revealing the height and shape of the hardware we left behind. You’re looking at discarded equipment that has been sitting in a vacuum for over fifty years, perfectly preserved because there’s no wind to blow it over.

Walking Paths and Tire Tracks: The Apollo 17 Evidence

Apollo 17 was the big one. Harrison Schmitt and Eugene Cernan spent three days living in the Taurus-Littrow valley. They had the rover. They covered miles.

📖 Related: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

When you look at the LRO images of the Apollo 17 site, it’s messy. In a good way. You can see the "LRV tracks"—the lines left by the rover's mesh wheels—crisscrossing the gray soil. They look like faint, dark ribbons. Because the lunar soil (regolith) is darker underneath the surface, any disturbance leaves a permanent mark.

It’s kind of like walking across a dusty floor. Your footprints don't just disappear.

The most human detail in these Apollo landing sites photographed by LRO is the "ALSEP" area. This was the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package. The astronauts had to trudge back and forth between the Lander and the experiment site to set up seismometers and magnetometers. In the photos, you see a well-worn dark path between the two points. It is the lunar version of a "desire path" in a park. It’s the literal record of two guys doing their jobs on another world.

What Happened to the Flags?

This is a big point of contention for people. "Where is the flag?" they ask. "I don't see the stars and stripes!"

Well, you wouldn't. At 25cm resolution, a flag—which is thin and viewed from directly above—is basically invisible. However, we do have clues. On most missions, the LRO images show a small spot of shadow exactly where the flag was planted. This suggests the poles are still standing.

Except for Apollo 11.

Buzz Aldrin reported that when they ignited the engine to leave the Moon, he saw the flag get knocked over by the exhaust. Guess what? The LRO images of Tranquility Base show no flag shadow. The data matches the eyewitness account perfectly.

The flags themselves are almost certainly bleached bone-white by now anyway. The sun’s unfiltered UV radiation is brutal. Fifty years of that would strip the pigment off anything. So, even if you were standing right next to them, they’d look like white surrender flags. Kind of a poetic, if unintended, symbol of peace.

👉 See also: Maya How to Mirror: What Most People Get Wrong

The Mystery of the Shifting Dust

Some people look at these photos and wonder why the tracks are dark. On Earth, we think of shadows as dark, but the tracks themselves are actually darker than the surrounding dust. This is because of "optical maturity."

The very top layer of the Moon is constantly bombarded by "space weathering"—tiny micrometeorites and solar wind. This makes the surface brighter over time. When an astronaut boots up that dust or a rover tire turns it over, they expose the "fresh" soil underneath, which hasn't been bleached by the sun. It’s the opposite of how we think of things fading in the sun here on Earth.

Why Other Countries See the Same Thing

If you don't trust NASA, that's fine. Science doesn't require "trust" when you have peer review and independent verification.

India’s Chandrayaan-2 mission recently took its own high-resolution photos of the Apollo 11 site. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) also mapped the landing sites with their SELENE/Kaguya orbiter. While Kaguya’s camera wasn't quite as sharp as the LRO's, it clearly identified the "halo" of disturbed soil created by the Lunar Module’s descent engine.

Basically, every country that sends a camera to the Moon sees exactly what NASA said was there. It’s a hard pill to swallow if you’re committed to the conspiracy, but the Apollo landing sites photographed by international agencies provide a level of redundancy that's hard to argue with.

The Lunar Environment: A Natural Museum

One thing that surprises people is how "clean" the sites look. There's no trash blowing around. There’s no rust.

Without oxygen, metal doesn't oxidize. Without liquid water, there's no erosion in the traditional sense. The only thing "weathering" the Apollo sites is the slow, relentless rain of micrometeoroids—dust particles smaller than a grain of sand traveling at tens of thousands of miles per hour.

Eventually, over millions of years, these particles will sandblast the Lunar Modules into nothing. But for now, they are perfectly preserved. We’re looking at 1960s technology sitting in a 2026 world, completely untouched since the day the crews left.

✨ Don't miss: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

Exploring the Apollo 12 and Surveyor 3 Connection

One of the coolest sets of Apollo landing sites photographed involves Apollo 12. This was the "precision landing" mission. Pete Conrad and Alan Bean landed so accurately they were able to walk over to the Surveyor 3 probe, which had landed on the Moon two years earlier.

In the LRO shots, you can see the Apollo 12 Lunar Module (Intrepid) on one side of a crater and the Surveyor 3 probe on the other. You can see the footpaths the astronauts took as they walked around the rim of the crater to reach the probe. They even cut pieces off Surveyor 3 to bring back to Earth to see how the materials held up.

When those parts were analyzed back on Earth, scientists found something crazy: Streptococcus mitis bacteria. It had survived in a dormant state for years on the lunar surface inside the camera housing. It’s a reminder that where we go, we bring life with us, even if it's just a few microbes on a piece of equipment.

Misconceptions About Photo Quality

Why aren't the photos in color? Why do they look like grainy black-and-white security footage?

The LRO’s Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) is designed for scientific mapping, not Instagram. It captures images in grayscale because that allows for higher resolution and better contrast of the lunar features. Color isn't really "color" on the Moon anyway—it’s mostly just different shades of charcoal and light gray.

Also, remember that these photos are taken from miles away while moving at over 3,000 miles per hour. The fact that we can see a 2-foot wide rover track at all is a feat of engineering.

Actionable Insights: How to See Them Yourself

You don't have to take my word for it. You can actually go and look at these images yourself. NASA doesn't hide them; they’re public record.

- Visit the LROC Quickmap: This is an interactive map of the Moon provided by Arizona State University. You can zoom in on the Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, and 17 sites.

- Look for the "Blast Halo": When you find a site, look for a lighter-colored area around the center. That’s where the rocket engine blew away the top layer of dust during landing.

- Check the timestamps: NASA provides the "Solar Incidence Angle" for each photo. This tells you where the sun was. If you want to see the hardware clearly, look for photos taken when the sun was low on the horizon—the long shadows make the objects pop.

- Compare with Astronaut Photos: Take an LRO overhead shot and compare it to the photos the astronauts took on the ground. You can match up specific rocks and craters. It’s like a 240,000-mile game of "I Spy."

The Moon is a graveyard of our early ambitions. It’s a place where time stands still. Looking at these Apollo landing sites photographed from orbit isn't just about debunking old myths; it’s about reconnecting with a time when we did something truly impossible. The tracks are still there. The machines are still there. They’re just waiting for someone to go back and kick up a little more dust.

To get the best experience, head over to the LROC (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera) gallery. Search for "Apollo" in their featured sites section. You’ll find high-resolution TIF files that you can download. Warning: they are huge. But if you want to see the literal footprints of Neil Armstrong from your living room, that's the place to go.

Spend some time looking at the Apollo 14 site specifically. The tracks there are particularly clear because Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell had to lug a "modular equipment transporter" (basically a lunar rickshaw) through the hills, leaving very distinct double-lines in the soil. It’s probably the most "human" looking site of the bunch. Seeing those tracks lead up to the rim of Cone Crater, where the astronauts almost got lost, makes the history books feel a lot less like a story and a lot more like a memory.