You’re sitting there, staring at a 1,200-year gap in your memory, wondering if the Abbasid Caliphate actually matters for your score. It does. But probably not in the way you think. Most kids hunting for ap world history practice tests are looking for a magic bullet—a set of leaked questions or a shortcut that bypasses the sheer mountain of content College Board expects you to climb. Honestly? Most of the practice material you find for free online is absolute garbage. It’s either too easy, focusing on rote memorization of dates, or it’s ancient, predating the massive 2019 "Modern" curriculum split that chopped off everything before 1200 CE.

Let's get real for a second.

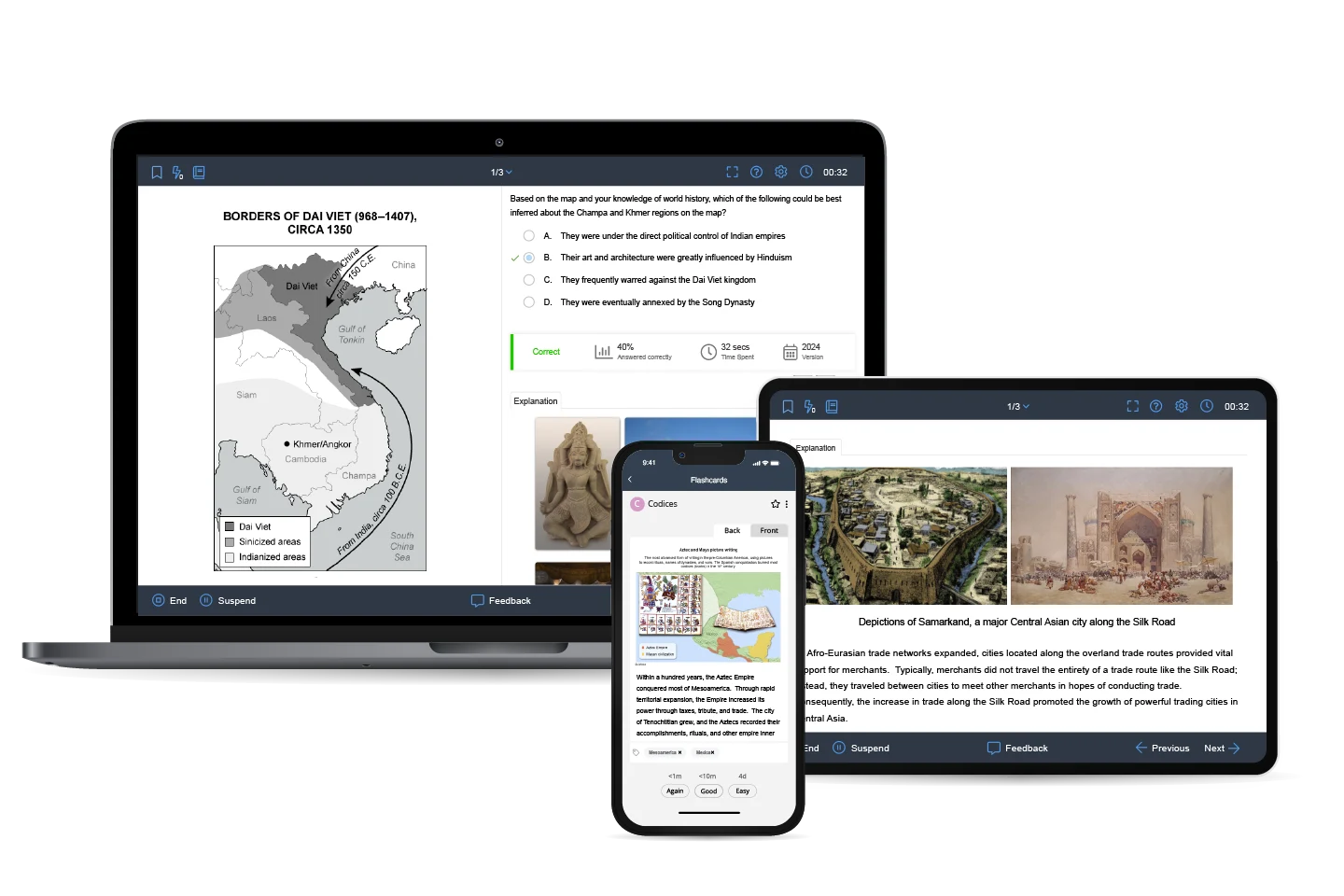

The AP World History: Modern exam isn't a history test. Not really. It’s a reading comprehension and data analysis test disguised as a history exam. If you’re just taking practice tests to see how many facts you know, you're going to get steamrolled by the stimulus-based multiple-choice questions (MCQs) that require you to interpret 16th-century woodcuts or obscure Portuguese merchant diaries.

The Problem With Random AP World History Practice Tests

There is a huge difference between a "high-quality" practice test and a "random PDF I found on a subreddit." The College Board changed the game a few years ago. They moved away from "What year did the Mongols take Baghdad?" to "Based on this map of trade routes, which of the following best explains the spread of the Bubonic Plague?"

See the shift?

👉 See also: Slow Cooker Beef Casserole and Dumplings: Why Your Meat Is Dry and Your Suet Is Soggy

One requires a brain; the other requires a flashcard. If your practice tests aren't using "stimulus" sets—basically a quote or an image followed by 3-4 questions—you are wasting your time. You've got to train your eyes to scan the source line first. Who wrote this? When? If it’s a 19th-century British official talking about India, you already know there's a heavy dose of paternalism and "civilizing mission" rhetoric coming your way before you even read the first sentence.

Where the Good Stuff Actually Lives

Don't just Google "free practice test" and click the first link. That’s how you end up taking a test from 2014 that asks about the Olmecs (not on the exam anymore, sorry).

- AP Classroom: This is the gold standard. Your teacher has access to the "Question Bank." These are retired questions from actual exams. If your teacher hasn't unlocked these for you, beg them. This is the only place you'll get the exact "vibe" of the real test.

- The 2017-2021 Released Exams: You can find these if you dig through the College Board’s archives or sites like CrackAP. They reflect the modern structure.

- Barron’s vs. Princeton Review: It’s an age-old debate. Barron's is notoriously harder than the actual exam. If you're getting a 3 on a Barron’s practice test, you’re probably headed for a 4 or 5 on the real thing. Princeton Review is "fluffier" but closer to the actual difficulty level.

The Multiple Choice Trap

You have 55 minutes to answer 55 questions. That sounds like a lot of time. It isn't. You’ll spend most of that time reading.

The biggest mistake students make on ap world history practice tests is reading the entire stimulus first. Stop doing that. Read the source info at the top. Read the question. Then skim the text for the answer. Often, the question is barely about the text at all; it’s asking about the historical context of the era the text represents.

For example, you might get a long-winded paragraph from a Japanese emperor during the Meiji Restoration. The question asks about industrialization. If you know the Meiji Restoration was about rapid modernization to avoid Western colonization, you can answer the question without deciphering the archaic 19th-century translation. You're saving minutes. In this exam, minutes are points.

Breaking Down the Writing Sections

Practice tests aren't just about the A-B-C-D bubbles. You’ve got the SAQs (Short Answer Questions), the DBQ (Document-Based Question), and the LEQ (Long Essay Question).

The DBQ is the beast. It’s worth 25% of your total score. You get seven documents and 60 minutes. Most people fail here because they "quote" the documents. Do not quote. The graders hate it. They want you to use the document to support an argument. If you’re practicing, focus on the "HIPPO" or "HAPP" method: Historical context, Audience, Purpose, Point of View.

Pick one for each document. Just one.

Why Your Practice Scores Might Be Lying to You

You might be crushing your practice exams at home and then get a 2 on the actual test in May. Why? Environmental stress is part of it, sure. But usually, it's because you’re "soft grading" your essays.

Self-grading is hard. You’re biased. You think your thesis is "strong" because you wrote it. But the AP graders are looking for a very specific "line of reasoning." If your thesis is just "There were many similarities and differences in how empires grew," you get zero points. It’s too vague. A real thesis looks like: "While both the Ottoman and Mughal Empires utilized gunpowder technology to expand, they differed in their treatment of religious minorities, with the Ottomans employing the millet system while the Mughals, under Akbar, practiced greater syncretism."

That’s a point-earner. It’s specific. It’s messy. It’s history.

The Nuance of the 1200-1450 Period

A lot of practice material leans too hard on the later years (1750-present). While that's where the bulk of the points are, you cannot ignore the foundational stuff. If you don't understand the "Global Tapestry" (Unit 1) and the "Networks of Exchange" (Unit 2), you won't understand the later colonial reactions.

Think of history like a series of "if/then" statements.

💡 You might also like: Skechers Slip Ins for Women: Why Your Back and Feet Will Finally Thank You

- If the Mongols reopen the Silk Road...

- Then trade intensifies and the Black Death spreads...

- Then feudalism in Europe collapses because peasants realize they have bargaining power.

When you take a practice test, look for these threads. Don't just look for the answer; look for the why.

Real Strategies for High-Stakes Practice

Don't take a full, 3-hour practice exam every weekend. You'll burn out by March.

Instead, do "sprints." Set a timer for 15 minutes and do one set of stimulus MCQs and one SAQ. This builds the "mental twitch" required to switch gears between reading and writing.

Also, variety matters. Use different sources. If you only use one prep book, you get used to that author’s "voice." The actual AP exam writers have a very specific, somewhat dry academic tone. You need to be comfortable with that.

Check out the "Chief Reader Reports" on the College Board website. These are gold mines. The head grader literally writes a report every year saying, "Here is where students messed up, and here is what we wanted to see." If you read those alongside your ap world history practice tests, you're basically getting the cheat code. They often complain that students "narrate" instead of "analyze."

Analysis means explaining the "so what?"

- Narrative: "The British took over India."

- Analysis: "British colonial rule in India shifted from the private control of the East India Company to direct crown rule after the 1857 Rebellion, leading to a more structured but extractive economic relationship."

Don't Forget the Images

Modern exams love visuals. You might get a picture of a "Castas" painting from colonial Mexico. If you haven't seen one in a practice test, find one. You need to know that these paintings weren't just art; they were a tool of social hierarchy and control.

Or maybe a Soviet propaganda poster.

Or a photo of a woman in a factory during WWII.

The practice tests that only use text are failing you. History is visual. The exam is visual. Your brain needs to be trained to "read" an image just as well as a paragraph.

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit your materials: Throw out any practice tests written before 2019. They are teaching you content that won't be on the test and skipping the "Modern" focus.

- The "Source First" Rule: On your next MCQ practice, force yourself to write down the date and the author's role before you read the stimulus text.

- Thesis Drilling: Take five random prompts from past LEQs and write only the thesis statement for each. Don't write the essay. Just the thesis. Compare them against the official scoring rubrics.

- Focus on Units 3-6: This is the "meat" of the exam (1450-1900). If you're short on time, prioritize practice questions from these eras, as they bridge the gap between the old world and the modern globalized state.

- Simulate the "Wall": Once before the actual exam, take a full-length test in a library or a loud-ish cafe. You need to know how your brain handles the 2-hour mark when the "history fatigue" sets in.