The AP World History Document-Based Question is a beast. You’re sitting there in a cold gym, hunched over a packet of seven random sources—maybe a map of the Silk Road, a disgruntled diary entry from a British merchant in Canton, and a colonial-era census—and you have to weave them into a coherent argument in about an hour. It’s stressful. Honestly, most students panic and start summarizing the documents like they’re writing a book report for middle school. That is the fastest way to tank your score.

The AP World DBQ rubric isn't actually designed to test if you're a genius historian. It’s a checklist. If you treat it like a scavenger hunt rather than a creative writing assignment, you’ll win. College Board isn't looking for Shakespeare; they’re looking for specific cognitive "moves." If you make the move, you get the point. If you don't, you don't. It is remarkably clinical once you strip away the academic jargon.

The Thesis is the Foundation (And Most People Mess It Up)

You cannot get a 7/7 without a thesis. Well, technically you could get other points, but a bad thesis sabotages your entire essay structure. According to the official College Board guidelines, a thesis must be "regionally and temporally consistent." That basically means you can't talk about the French Revolution if the prompt is about the Mongols.

✨ Don't miss: Female Air Force Blues Uniform: What Most People Get Wrong About the Wear and Use

A good thesis does two things: it responds to the prompt and it lays out a roadmap. Don't just restate the question. If the prompt asks how trade changed in the Indian Ocean from 1450 to 1750, don't just say "Trade in the Indian Ocean changed a lot because of many factors." That’s a zero. You need to say how it changed. Maybe mention the arrival of the Portuguese armed trade or the shift from luxury goods to bulk commodities. You've gotta be specific.

One thing that’s kinda wild is that the thesis can be anywhere in the introduction or the conclusion. But seriously, just put it at the end of your first paragraph. Why make the grader hunt for it? These people are grading hundreds of essays a day. They’re tired. They’re hungry. Make their lives easy by putting your claim right where they expect it.

The "Contextualization" Point: Setting the Stage

Think of contextualization like the "previously on..." segment at the start of a TV show. You need to explain what was happening in the world before or during the time period of the prompt that led up to the events you’re discussing.

It has to be more than a passing phrase. You can't just say "Silk Road trade was big." You need to describe the broader trends. If you're writing about the 19th-century New Imperialism, you should probably talk about the Industrial Revolution. Why? Because the need for raw materials and new markets drove European powers to scramble for Africa. That’s context. It’s the "why" behind the "what."

Usually, three to four solid sentences at the very beginning of your essay will nail this point. It’s an easy point, yet so many students skip it because they’re in a rush to get to the documents. Don't be that person.

Mastering the Documents in the AP World DBQ Rubric

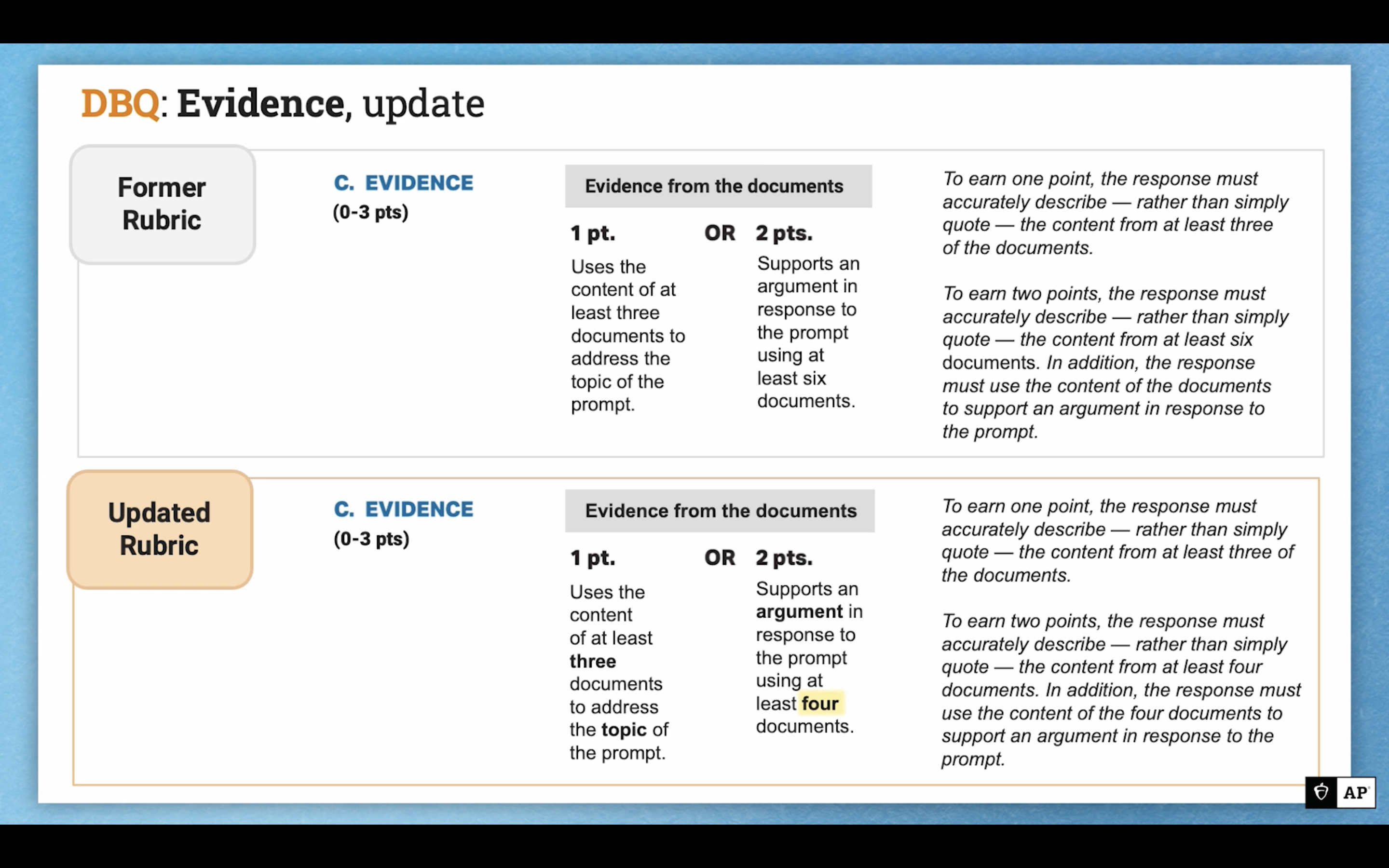

This is where the meat of the points lives. You get one point for using the content of at least three documents to address the prompt. You get a second point for using six documents to support an argument.

There is a massive difference between "using" and "supporting."

"Using" is just: "Document 1 says that the Ming Dynasty stopped treasure voyages."

"Supporting" is: "The Ming Dynasty’s decision to halt treasure voyages, as seen in Document 1, illustrates a broader shift toward neo-Confucian isolationism and a focus on northern border defense."

👉 See also: Why Cowboy Boots on Women Are Actually Hard to Get Right

See the difference? One is a summary. The other is a tool.

Sourcing: The "HIPPO" or "HIPP" Method

You also need to "source" at least three documents. This means you explain why the document says what it says. You look at:

- Historical Situation: What was happening when this was written?

- Intended Audience: Who was this meant for? (A secret letter is different from a public speech).

- Point of View: Is the author a wealthy merchant or a peasant? How does that bias them?

- Purpose: Why did they write this? Are they trying to persuade someone or just record facts?

Honestly, point of view is usually the easiest one to grab. If you have a document from a Spanish conquistador talking about how "civilized" the Aztecs were becoming under Spanish rule, his POV is pretty obvious. He’s trying to justify colonization to the King.

Outside Evidence: The Ninja Move

The AP World DBQ rubric requires you to bring in one piece of specific historical evidence that is not found in the documents. This is your chance to show off.

👉 See also: St Bernard Dog Size: What Most People Get Wrong About These Giants

It has to be a specific "noun." You can't just say "religion was important." You need to say "The Edict of Nantes" or "The Taiping Rebellion." It needs to be a specific event, person, or law that supports your argument but isn't mentioned anywhere in the prompt's source list. You only need one, but I always tell people to aim for two. If you mess up the first one, the second one is your safety net.

The "Complexity" Unicorn

The seventh point is the Complexity Point. It’s legendary. It’s rare. Some years, only 1% of students get it.

You don't get it just by writing a long essay or using big words. You get it by showing that history isn't black and white. You have to demonstrate a "complex understanding." This usually means:

- Corroboration: Showing how multiple documents agree in nuanced ways.

- Qualification: Acknowledging the "other side." (e.g., "While trade led to wealth for the elites, it simultaneously caused the displacement of indigenous populations.")

- Contradiction: Explaining why two documents might say the exact opposite thing and why both are still "true" in their context.

Most people fail this because they try to "tack it on" at the end. Complexity has to be woven through the whole essay. It's the difference between a high school essay and a college-level historical analysis. If you're aiming for a 5 on the exam, this is the point you should be chasing, but don't sacrifice the "easy" points like sourcing and evidence to get it.

Common Traps to Avoid

One of the biggest mistakes is "quoting" too much. If your essay is 50% direct quotes, you're going to lose points. The graders already know what the documents say—they have the key! They want to see your analysis. Paraphrase everything. Use the author's name or the document number in parentheses, but keep the focus on your argument.

Another trap? Forgetting the prompt. It sounds stupid, but in the heat of the moment, it's easy to start writing about something tangentially related and forget to actually answer the specific question asked. If the prompt asks for "social impacts," and you only write about "economic impacts," you are in trouble.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Practice DBQ

To actually get better at the AP World DBQ rubric, you need to stop reading about it and start doing it.

- Practice "Grouping" Documents: Take a set of documents and try to put them into three "buckets" or themes. Do this in under five minutes. If you can't group them, you can't write a roadmap.

- Drill Sourcing: Take one document and write three different sentences for it: one for Purpose, one for Audience, and one for POV. See which one feels more natural for that specific source.

- The 15-Minute Plan: Spend the first 15 minutes of your practice sessions just reading, annotating, and outlining. Do not start writing until you know exactly what your three body paragraphs will be.

- Annotate the Rubric: Print out the official College Board rubric and check off the points as you write your practice essays. If you can't point to the sentence in your essay that gets the "Evidence Beyond the Documents" point, you haven't earned it yet.

- Focus on the Nouns: When you're stuck, think of specific people or events from that time period. The more "proper nouns" you use correctly, the more likely you are to secure the evidence and context points.

The exam isn't a mystery; it’s a game with a very specific set of rules. Once you memorize the AP World DBQ rubric, the "history" part actually becomes the easy bit. You're just filling in the blanks of a pre-set structure that College Board has already given you.

Immediate Next Steps

- Review the 2024 and 2025 Past Prompts: Go to the College Board website and look at the "Student Samples." Read a 7/7 essay and then read a 3/7 essay. You will immediately see the difference in how they handle the documents.

- Build a "Context Bank": For each of the nine units in AP World, memorize two or three "big picture" events that you can use for contextualization. If a prompt comes up about Unit 4 (1450-1750), you should immediately think: "Columbian Exchange, Maritime Empires, Silver Trade." That’s your context starter pack.