You’ve spent months deriving equations for Atwood machines and memorizing exactly how a solid sphere rolls down an incline compared to a hollow hoop. You know the math. But then you sit down for the AP Physics Mechanics multiple choice section, and suddenly, the clock is screaming. 45 minutes. 35 questions. That is roughly 77 seconds per problem. If you’re spending three minutes calculating the tension in a rope, you’ve already lost.

The College Board isn't just testing your ability to plug numbers into $F=ma$. They are testing your physical intuition. Honestly, the biggest mistake people make is treating this section like a math test. It isn't. It is a logic puzzle wrapped in Greek letters.

The Brutal Reality of the 45-Minute Sprint

The pace is relentless. Unlike the Free Response Questions (FRQ) where you can scavenge for partial credit by showing your work, the AP Physics Mechanics multiple choice is binary. You’re right or you’re wrong.

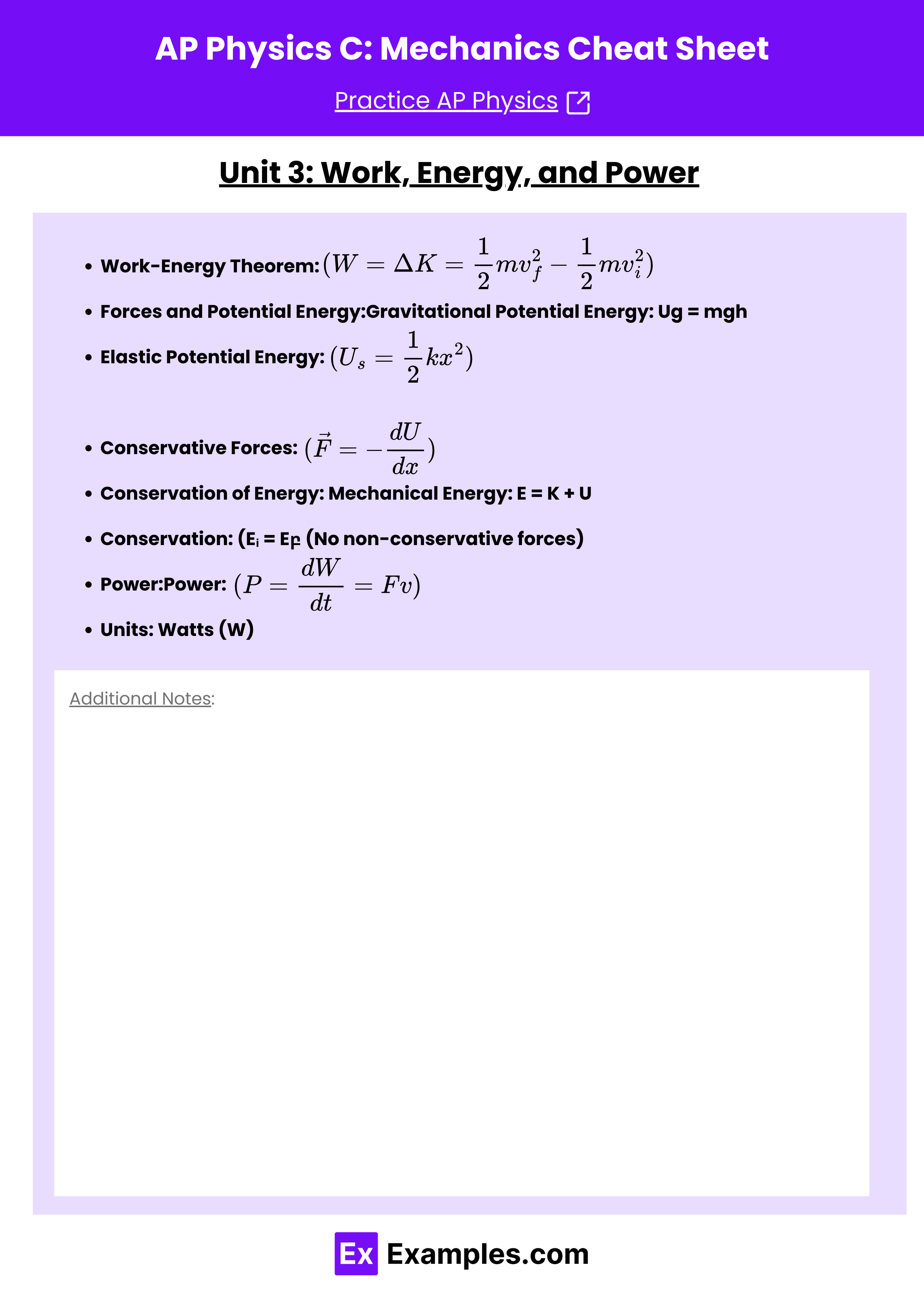

Most students walk into the room thinking they need to solve every problem from scratch. Wrong. If you are doing heavy algebra for a multiple-choice question, you are probably missing a conceptual shortcut. Take conservation of energy, for example. If a block slides down a frictionless track, its final velocity depends only on the change in height. It doesn't matter if the track is a straight line, a loop-de-loop, or a wiggly mess. If you start drawing free-body diagrams for every point on a curved path just to find a final speed, you’re wasting the very time you need for the "Select Two" questions at the end.

The Trap of "Calculus-Based" Physics

We call it AP Physics C because of the calculus. But here is a secret: the multiple-choice section barely uses it. Sure, you might see a position function like $x(t) = 3t^2 - 5t$ and need to find acceleration, which is just two quick derivatives. Easy.

But the real challenge is understanding the relationship between variables. If the power delivered to an object is constant, how does its velocity change over time? A lot of kids panic and try to integrate immediately. Instead, think about the units. Power is force times velocity ($P = Fv$). If $P$ is constant, and $F = m \frac{dv}{dt}$, then you have a differential equation. But you don't always need to solve it to pick the right graph. You just need to know if the slope is increasing, decreasing, or constant.

Why Rotational Dynamics is the "Gatekeeper"

If you want a 5, you have to master rotation. This is usually where the wheels fall off—literally. Roughly 18% to 22% of the AP Physics Mechanics multiple choice questions involve torque, rotational inertia, or angular momentum.

Consider the classic "rolling without slipping" scenario. A cylinder and a ring are released from the top of a hill. Students often forget that some of the potential energy has to go into rotational kinetic energy. The more "spread out" the mass is (like in a hoop), the more energy it "steaks" from the translational motion. Consequently, the hoop is slower.

The Torque Tangle

Torque is $\tau = r F \sin(\theta)$. In the multiple-choice section, they love to give you a wrench or a beam and ask where to apply a force to keep it in equilibrium.

- Check the pivot point.

- Sum the torques.

- Don't forget the weight of the beam itself, acting at the center of mass.

It sounds simple. It’s not. Especially when they add a second pivot or a moving person. You’ve got to be fast.

The "Select Two" Nightmare

At the very end of the section, you’ll hit a handful of questions where you must choose two correct answers. There is no partial credit. If you pick one right and one wrong, you get zero.

These questions are usually purely conceptual. They might ask which two quantities are conserved in a specific collision. Maybe it’s an inelastic collision where momentum is conserved but kinetic energy isn't. Or maybe it’s a system where external work is being done. These are designed to catch people who rely on "gut feeling" rather than strict definitions of systems.

Gravity and Orbits: Don't Get Loopy

Universal Gravitation is a gift if you know the formulas. $F_g = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}$.

Note the $r^2$.

If the distance doubles, the force doesn't halve. It drops by a factor of four.

If the orbit is circular, the gravitational force is the centripetal force.

$$G \frac{Mm}{r^2} = \frac{mv^2}{r}$$

Basically, the mass of the satellite ($m$) cancels out. This means a bowling ball and a space station orbit at the same speed if they are at the same altitude. This confuses people every single year. They think "more mass equals more gravity," which is true for force, but not for orbital velocity.

💡 You might also like: The macbook air 13 2020: Why This Specific Model Still Matters in 2026

Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM) is Just Circles in Disguise

Many students treat SHM as this weird, isolated topic. It’s actually just a projection of circular motion. When you see a mass on a spring, your brain should immediately jump to:

- $T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{m}{k}}$

- Max velocity occurs at the equilibrium point ($x=0$).

- Max acceleration occurs at the amplitudes ($x = A$).

If a question asks what happens to the period if you move the spring system to the Moon, the answer is nothing. Gravity ($g$) isn't in the equation for a spring's period. But if it’s a pendulum? Then $T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{L}{g}}$, and you’re in trouble. Recognizing which variables actually matter is the difference between a 3 and a 5 on the AP Physics Mechanics multiple choice.

Laboring Over Labs

About 5-10% of the questions are lab-based. They’ll show you a messy graph of $v^2$ vs. $\Delta x$ and ask you to find the acceleration.

Think about the kinematics equation: $v^2 = v_0^2 + 2a\Delta x$.

If you plot $v^2$ on the y-axis and $\Delta x$ on the x-axis, the slope is $2a$.

Linearizing data is a massive part of the modern AP curriculum. If you can't look at a non-linear relationship and figure out how to make it a straight line, you're going to struggle with the data-analysis questions.

Strategies for the Final Countdown

You cannot treat this like a standard test. You need a "triage" system.

The First Pass

Go through and answer every "definition" question. If it’s a conceptual question about work-energy or a simple 1D kinematics problem, do it immediately. If you see a multi-body system with friction and angles, skip it. Circle it and move on.

The Second Pass

Now tackle the problems that require one or two lines of algebra. This is where you spend your time. Focus on the conservation laws first—energy and momentum are usually faster to solve than Newton’s Second Law.

The "Hail Mary" Pass

With five minutes left, you have to bubble everything. There is no guessing penalty. If you have three questions left that look like Greek to you, pick a letter and stick with it. Statistically, you’re better off picking "C" for all three than jumping around.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Internal vs. External Forces: If you define your "system" as both blocks, the tension between them is an internal force and does no work on the system. If you forget this, you'll waste time calculating work that cancels out anyway.

- The "Static Friction" Trap: Static friction is an inequality: $f_s \leq \mu_s F_n$. It is only equal to $\mu_s F_n$ at the very moment the object starts to budge. If the applied force is $5N$ and the max static friction is $10N$, the actual friction force is $5N$, not $10N$.

- Signs and Directions: In mechanics, a negative sign just means "the other way." But if you’re calculating work, the sign is everything. Work is positive if the force and displacement are in the same direction.

Actionable Steps for Your Study Sessions

Don't just read the textbook. Physics is a doing sport.

- Practice with a timer. Do 10 problems in 12 minutes. Force yourself to feel the pressure of the 77-second limit.

- Memorize the "Proportionality" Relationships. If the radius of a planet triples and the mass doubles, what happens to $g$? You should be able to say "2/9ths" in under five seconds.

- Draw Every Scenario. Even a 5-second sketch of a free-body diagram can prevent you from forgetting a force like friction or gravity.

- Use Official Resources. The College Board's "AP Central" has past exams. Third-party prep books are okay, but sometimes they make the math too hard or the concepts too shallow. Stick to the source when possible.

- Master the Calculator. Know how to solve a basic quadratic or a system of equations on your TI-84 or Nspire. You shouldn't be doing long division in 2026.

Success on the AP Physics Mechanics multiple choice section comes down to one thing: recognizing patterns. When you see a pulley, you should already be thinking about torque and tension before you even finish reading the prompt. When you see a spring, you should be thinking about energy conservation. Get your brain to "pre-load" the physics, and the math will follow.

Next Steps for Mastery

To truly dial in your performance, start by taking a diagnostic 35-question set from a released exam. Grade yourself strictly on the 45-minute limit. Identify which of the six major units—Kinematics, Newton's Laws, Work/Energy, Momentum, Rotation, or Oscillations—caused the most "skips" or "time sinks." Focus your next three study sessions exclusively on your weakest unit, specifically practicing how to linearize data and identify conserved quantities without performing full calculations.