Let's be real. If you’re staring at a stack of AP Chem MC questions, you’re probably feeling that specific brand of dread that only comes from knowing you have 90 minutes to solve 60 problems that feel like they were written by someone who hates joy. It’s a grind. Honestly, the Multiple Choice Section (Section I) of the AP Chemistry exam is less about how much chemistry you know and more about how well you can navigate the traps the College Board sets for you.

Most students treat these questions like a trivia night. They think if they memorize the solubility rules or the periodic trends, they’re golden. They aren't.

The exam has shifted. Since the big redesign a few years back, the focus moved away from rote memorization toward data interpretation and conceptual "why" questions. You’ll see a particulate diagram and think, "Oh, neat, circles," but if you can't translate those circles into a limiting reactant calculation in thirty seconds, you're toast.

The Mental Game of AP Chem MC Questions

You’ve got roughly 90 seconds per question. That sounds like a decent amount of time until you hit a question about the thermodynamics of a galvanic cell that requires you to estimate a logarithm without a calculator. That's the kicker—no calculators in the MC section. If you’re trying to do long division to the fourth decimal point, you’ve already lost the game.

The College Board loves "estimation-friendly" math. If you see $6.022 \times 10^{23}$, they probably want you to just use $6 \times 10^{23}$. If the pressure is 0.98 atm, call it 1.

A huge chunk of AP Chem MC questions focus on Big Idea 3: Chemical Reactions, and Big Idea 4: Kinetics. But the real "boss fight" is often Big Idea 9, which covers Entropy and Gibbs Free Energy. Students get tripped up because the questions look easy. They’ll ask about the sign of $\Delta S$, and you’ll think, "Gas is more messy, so it’s positive." But then they throw in a temperature dependence twist, and suddenly you’re staring at four options that all look vaguely plausible.

Why the "Easy" Questions are Dangerous

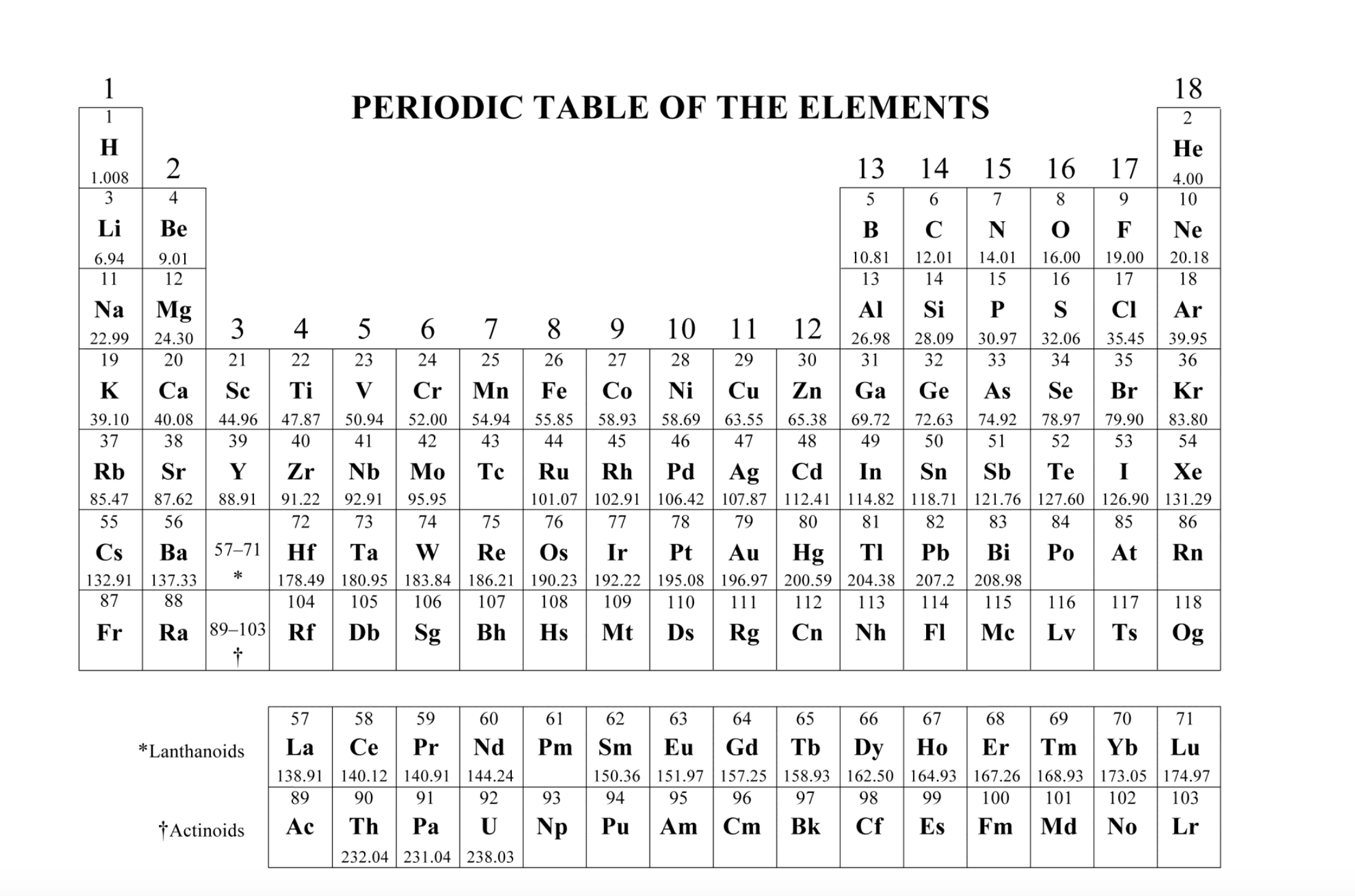

The "easy" questions are usually the ones about periodic trends or bonding. You see a question about electronegativity and your brain goes on autopilot. "Fluorine is the most electronegative," you whisper. But the question wasn't asking for the trend; it was asking for the justification based on Coulomb’s Law.

If your answer choice doesn't mention the distance between the nucleus and the valence electrons or the effective nuclear charge ($Z_{eff}$), it’s probably a distractor. The College Board is obsessed with Coulomb’s Law ($F = k \frac{q_1 q_2}{r^2}$). Seriously. If you’re stuck on a multiple-choice question about why an atom is smaller or why a bond is stronger, and one of the answers involves the distance between charges, that’s your leading candidate.

✨ Don't miss: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

The Particulate Diagram Trap

One of the most common types of AP Chem MC questions involves those little boxes filled with dots representing atoms or molecules. These are particulate models. They seem straightforward, but they are designed to test if you actually understand stoichiometry on a microscopic level.

Example: You have a box with 4 $H_2$ molecules and 4 $O_2$ molecules. They react to form $H_2O$. What’s left in the box?

Most people just count the atoms and pick a box that has the right number of H’s and O’s. But you have to identify the limiting reactant first. In this case, $H_2$ is your bottleneck. You’ll have leftover $O_2$. If you don't see those unreacted $O_2$ molecules in the "after" picture, that answer choice is wrong.

These questions take time to process visually. You have to be fast. You’re looking for conservation of mass, but you’re also looking for the correct physical state. If the reaction produces a liquid and the diagram shows molecules far apart like a gas, it’s a trap.

Acid-Base Equilibrium: The Scoring Killer

If you want to know where dreams go to die, it’s the equilibrium section. Specifically, weak acid/base titrations. In the multiple-choice section, they won't make you do a full ICE table—it takes too long. Instead, they’ll test your knowledge of the "half-equivalence point."

At the half-equivalence point, $pH = pK_a$. I’ve seen so many AP Chem MC questions where the entire solution hinges on that one fact. If you know the $pK_a$ is 4.7, and the pH is currently 4.7, you know exactly half of your acid has been neutralized. No math required. Just recognition.

Also, watch out for the "buffer zone." They love asking what happens to the pH when a small amount of $OH^-$ is added to a buffer. The answer is almost always "it stays basically the same," but they’ll phrase it in a way that makes you want to calculate the new molarity. Don’t fall for it.

Intermolecular Forces (IMFs) are Everywhere

You can't escape IMFs. They are the "background radiation" of the AP Chemistry exam. Whether it’s vapor pressure, boiling points, or solubility (like dissolves like), IMFs are the "why" behind the "what."

🔗 Read more: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

A favorite question style compares two substances, like ethanol and dimethyl ether. They have the same molecular formula but different structures. One has hydrogen bonding; the other doesn't. You'll be asked to explain why ethanol has a lower vapor pressure.

- Wrong Answer: "Ethanol is heavier." (It’s not).

- Wrong Answer: "Ethanol has stronger covalent bonds." (Irrelevant; we aren't breaking the molecules apart).

- Correct Answer: "Ethanol has stronger IMFs (hydrogen bonding), requiring more energy to overcome the attractions between molecules."

How to Actually Practice

Stop doing questions in a vacuum. If you’re just clicking through a random quiz site, you’re not learning the "flavor" of the actual exam. Use the released exams from the College Board. Even the ones from 2014-2019 are still incredibly relevant.

When you get a question wrong, don't just look at the right answer and say "Oh, I knew that." You didn't. If you did, you wouldn't have missed it. Write down why the distractor was tempting. Was it a "sign" error in thermodynamics? Did you forget that $AgCl$ is insoluble?

The "Skip" Strategy

If you read a question and your brain feels like it’s buffering, skip it. Immediately.

There are 60 questions. Some are "Level 1" (What’s the oxidation state of Manganese in $KMnO_4$?) and some are "Level 5" (Calculate the $K_{sp}$ based on a graph of conductivity). They are all worth the same point. You don't get bonus points for suffering through a hard question for five minutes and getting it right, only to miss five easy questions at the end because you ran out of time.

Specific Topics That Frequently Appear

- Photoelectron Spectroscopy (PES): Look at the peaks. The height of the peak is the number of electrons. The position (x-axis) is the binding energy. The peaks further to the left (higher energy) are the ones closest to the nucleus (1s).

- Kinetics and Order: If doubling the concentration doubles the rate, it's first order. If it quadruples the rate, it's second order. If it does nothing, it's zero order. You will almost certainly see a table of initial rates. Learn to do this math in your head.

- Enthalpy of Formation: Remember $\Delta H_{rxn} = \sum \Delta H_f (products) - \sum \Delta H_f (reactants)$. It’s always products minus reactants. They will give you a table. Watch your signs. A negative minus a negative is a positive. This is where most students fail—simple 4th-grade arithmetic.

The Lab-Based Questions

The AP exam has leaned heavily into "lab-based" scenarios in the MC section. You might see a description of a student's error. "A student forgot to dry the beaker before weighing the precipitate. How does this affect the calculated molar mass?"

Think it through:

💡 You might also like: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

- Extra water means a higher mass reading.

- Higher mass looks like more product.

- More product makes it seem like you had more moles of reactant.

- If you’re calculating molar mass ($g/mol$), and your grams are artificially high, your calculated molar mass will be too high.

These "error analysis" questions are a staple. They test if you actually understand the equipment (burets, pipets, analytical balances) or if you’re just a formula-memorizing robot.

Actionable Steps for Your Study Sessions

Don't just "study." Execute. Here is how you should handle your next session with AP Chem MC questions.

First, get a timer. Set it for 15 minutes and try to do 10 questions. This forces you to feel the 90-second pace. It’s uncomfortable, but necessary.

Second, categorize your misses. Are you missing "Content" (I forgot what a pi bond is) or "Process" (I did the math wrong)? If it’s content, hit the textbook or a video. If it’s process, you need more practice under pressure.

Third, master the "Process of Elimination." In many questions, two of the four options are objectively ridiculous. If a question asks about an exothermic reaction, and two of the answer choices describe the surroundings getting colder, cross them out instantly. You’ve just doubled your odds of guessing correctly.

Finally, pay attention to the state symbols in chemical equations. $(s)$, $(l)$, $(g)$, and $(aq)$ are not decorations. They are instructions. If the equation shows a gas being produced from solids, $\Delta S$ is positive. If you miss that $(g)$, you've lost the point before you even started the problem.

Go back through your last practice test. Highlight every question where you were stuck between two choices. Usually, the difference between those two choices is one single word—like "atom" vs "ion" or "inter" vs "intra."

Chemistry is a language. The MC section is the reading comprehension test. Treat it like one, and the numbers will start to take care of themselves. Focus on the relationships between variables ($P$ and $V$, $T$ and $K$, $E$ and $G$) rather than trying to solve for "x" every time. Most of the time, the College Board just wants to see if you know which way the scale tips when you add a little weight to one side.