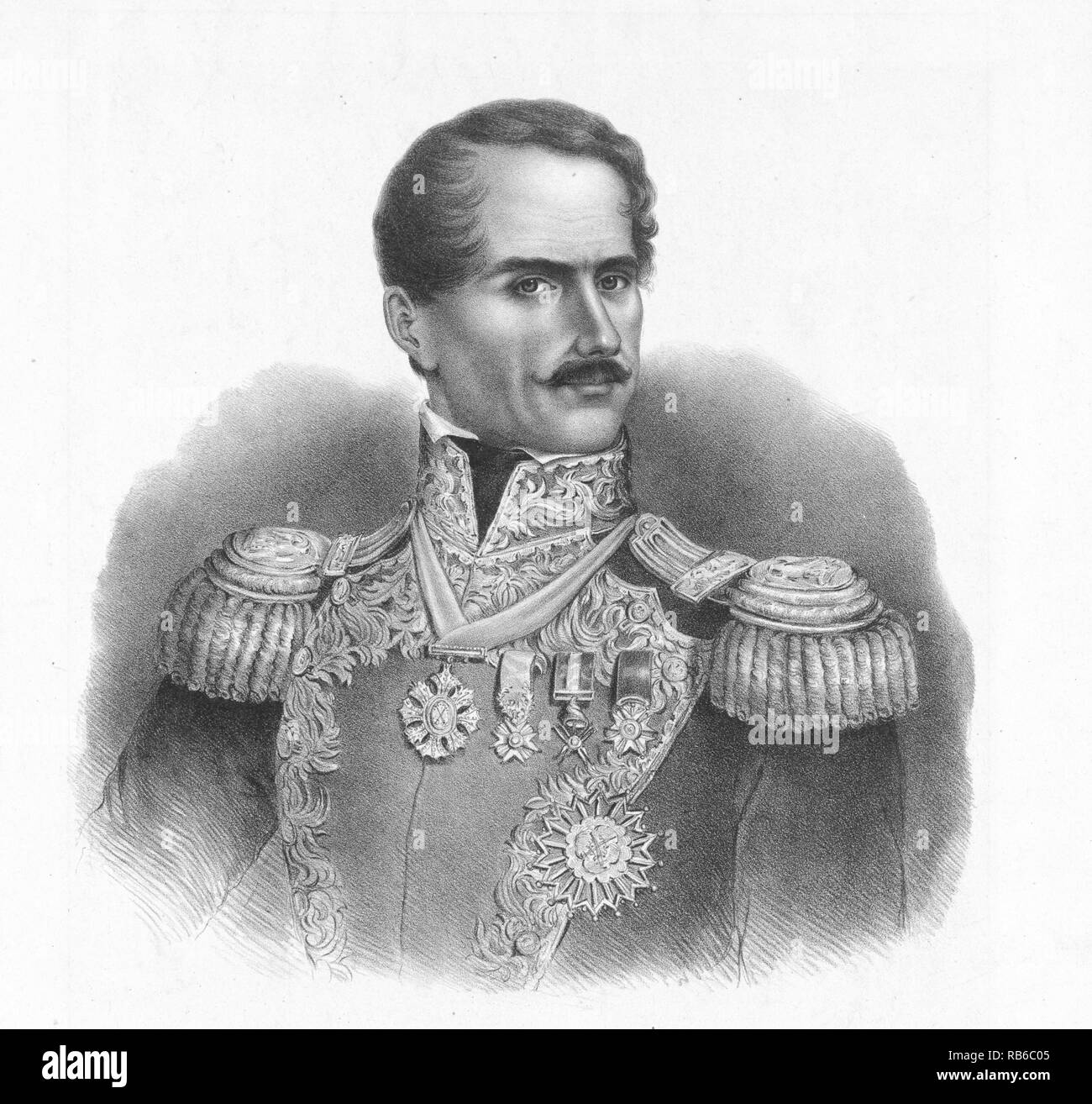

He was called the "Napoleon of the West." He was also called a traitor, a savior, and, by his own decree, "Most Serene Highness." If you’re looking for a simple hero or a straightforward villain in history, you won't find one here. Antonio López de Santa Anna, the man who served as president of Mexico eleven different times, is basically the personification of 19th-century political chaos.

Think about that for a second. Eleven times.

In a modern democracy, that sounds like a glitch in the system. But for Mexico between 1833 and 1855, it was just Tuesday. Santa Anna didn't just lead the country; he hovered over it like a storm cloud that wouldn't dissipate. He was a master of the "Caudillo" style of leadership—part military strongman, part populist rockstar, and part opportunistic politician who could switch sides faster than a weather vane in a hurricane.

People often wonder how one man could lose so much territory—specifically the land that became Texas, California, Arizona, and New Mexico—and still keep getting invited back to the National Palace. Honestly, it comes down to charisma and a vacuum of power. When things got bad, Mexico looked for a "Man of Destiny." Santa Anna was always happy to play the part, even if he usually ended up making things worse.

The General Who Would Be King (or Anything Else)

Santa Anna didn't start at the top. He was born in Jalapa, Veracruz, in 1794. He was a middle-class kid who skipped a career in commerce to join the Spanish royal army. Back then, Mexico was still New Spain.

He learned his craft by fighting insurgents. Funny enough, he eventually turned on his Spanish masters to join the push for Mexican independence under Agustín de Iturbide. This was his first big flip. It wouldn't be his last. By the time he helped topple Iturbide (who had declared himself Emperor), Santa Anna had realized something crucial: in a young, fractured nation, the person with the loudest voice and the sharpest sword wins.

By 1833, he finally became president of Mexico for the first time. But here's the kicker—he didn't actually want to do the job of governing. He found the day-to-day paperwork of the presidency incredibly boring. He left the actual work to his vice president, Valentín Gómez Farías, and retired to his massive estate, Manga de Clavo, to wait for something more exciting to happen.

He was a man of action, not a man of spreadsheets.

The Texas Disaster and the Leg

If you're American, you probably know him as the "bad guy" from the Alamo. In 1835, Santa Anna decided to centralize power in Mexico City, basically ripping up the federalist Constitution of 1824. This ticked off a lot of people, including the settlers in Texas.

💡 You might also like: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

What followed was a brutal campaign. Santa Anna marched north, won a pyrrhic victory at the Alamo, and then committed a massive strategic blunder at San Jacinto. He was caught literally napping. Sam Houston’s forces routed the Mexican army in about 18 minutes.

Santa Anna was captured while wearing a private's uniform to hide his identity. To save his life, he signed the Treaties of Velasco, acknowledging Texas independence. When he got back to Mexico City, the people were understandably furious. You’d think that would be the end of his career.

Nope.

In 1838, the French invaded Veracruz in what became known as the "Pastry War" (yes, it started over a debt to a French baker). Santa Anna rushed to the front. During the fighting, a French cannonball hit his leg. Doctors had to amputate it.

He turned this tragedy into a PR masterclass.

He had the leg buried with full military honors. He portrayed himself as the wounded martyr who had literally given a piece of himself for the fatherland. This "sacrifice" washed away the shame of Texas. He was back in power before the ink on his medical charts was dry.

Why He Kept Coming Back

It's tempting to think the Mexican public was just gullible. It’s more complicated than that. Mexico in the 1840s was a mess. The treasury was empty. The army was unpaid. The church and the liberals were at each other's throats.

In this environment, a "strongman" feels like a safety net. Santa Anna was a brilliant orator. He knew how to stir up nationalistic fervor. He was the only person who could bridge the gap between the conservative elites and the common soldiers. Even when he failed, there was nobody else with his name recognition to take the reins.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

The Mexican-American War: The Final Blow

The defining moment for his legacy—and the one that still stings in Mexican history books—is the Mexican-American War (1846–1848).

At the start of the war, Santa Anna was actually in exile in Cuba. He pulled off a legendary scam. He contacted the U.S. government and told them that if they let him back into Mexico through their naval blockade, he would negotiate a peace deal favorable to the United States. President James K. Polk actually fell for it.

Once Santa Anna stepped foot on Mexican soil, he immediately betrayed the Americans. He took command of the Mexican army and prepared to fight.

It didn't go well.

Despite having the home-field advantage and, at times, superior numbers, the Mexican forces were plagued by internal bickering and poor logistics. Santa Anna fought bravely at the Battle of Buena Vista, but he ultimately couldn't stop Winfield Scott's march on Mexico City.

The resulting Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was a catastrophe for Mexico. It ceded 55% of its territory to the U.S. We’re talking about the modern-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, most of Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming.

Mexico was humiliated. Santa Anna went into exile again.

But, like a recurring villain in a soap opera, he returned in 1853. This time, he went full dictator. He took the title "Sovereign Revolutionary General" and later "Most Serene Highness." He even sold more land—the Gadsden Purchase—to the U.S. for $10 million just to pay for his lavish lifestyle and his army.

👉 See also: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

That was the breaking point. The Revolution of Ayutla finally kicked him out for good in 1855.

The Real Legacy of Santa Anna

When people talk about the president of Mexico during this era, they often focus on the maps. They look at the "before and after" of the border. But the real tragedy of Santa Anna’s reign wasn't just the land; it was the lost decades.

While the U.S. was industrializing and expanding, Mexico was stuck in a cycle of coups and counter-coups led by a man who cared more about his own glory than building a stable nation. He left Mexico broke, divided, and deeply traumatized.

Historians like Enrique Krauze have pointed out that Santa Anna represented a "patrimonial" style of leadership. He viewed the country as his personal hacienda. He wasn't unique in this—many Latin American leaders of the time did the same—but he was the most successful at it.

What You Can Learn From This Today

If you study Santa Anna's life, there are some pretty clear, albeit harsh, lessons about leadership and national stability:

- Charisma is a double-edged sword. A leader who can talk his way into power can often talk his way out of responsibility. Santa Anna's ability to charm his way back into the presidency repeatedly delayed the development of actual democratic institutions.

- Centralization creates fragile states. By trying to control everything from Mexico City, Santa Anna alienated the frontier regions (like Texas and California), making them easier to lose.

- The "Cult of Personality" is a trap. When a nation's identity is tied to one person rather than a constitution or a set of laws, the nation falls whenever that person fails.

Moving Forward: How to Explore This History

If you want to understand the modern relationship between the U.S. and Mexico, you have to understand this man. He isn't just a figure from a dusty textbook; his decisions literally drew the lines on the map you see today.

Next Steps for the History Buff:

- Read Primary Sources: Look up the "Manifesto of San Luis Potosí." It gives you a direct look into how Santa Anna justified his actions to the public.

- Visit the Sites: If you're ever in Mexico City, go to the National Museum of Interventions (Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones). It’s housed in a former monastery where a major battle took place, and it provides a perspective on these wars that you won't get in American schools.

- Check out "The Eagle" by Will Fowler: If you want a deep, scholarly dive that moves beyond the "cartoon villain" version of Santa Anna, this is the definitive biography.

The story of the president of Mexico who lost half his country is a reminder that history isn't just made by grand movements—it's often driven by the ego, the mistakes, and the wooden leg of a single, deeply flawed man.