You’ve probably seen the movie. Or maybe you read the Diane Ackerman book. It’s a hell of a story: a zookeeper and his wife hiding hundreds of Jews right under the noses of the Nazis, tucked away in empty animal cages. But honestly, the Hollywood version—as good as it is—kinda smoothens out the edges of a reality that was way more gritty, stressful, and strategically complex than a two-hour film can show.

Antonina and Jan Zabinski weren't just "kind people." They were high-stakes gamblers playing a game where the house always won, and the penalty for losing wasn't just a fine—it was a bullet for them and their kids.

The "Noah's Ark" Strategy

When the Luftwaffe bombed Warsaw in 1939, the zoo didn't just close. It was decimated. Many animals died in the blasts; others, the "valuable" ones like Tuzinka the elephant, were shipped off to Germany by Lutz Heck, the Nazi-appointed overseer who Jan actually knew before the war. The ones left? Heck and his men shot them in a "hunting" spree. It was brutal.

But the Zabinskis stayed. Jan was a scientist, an expert in zoology, and a lieutenant in the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa). He wasn't just a passive observer. He convinced the Germans to let him turn the ruined zoo into a pig farm. Why? Because pigs eat meat, and meat requires "waste" collection.

That "waste" collection gave Jan a legal permit to enter the Warsaw Ghetto.

Once inside, he wasn't just looking for scraps. He was smuggling in food and forged documents. More importantly, he was smuggling people out. He’d bring them back to the zoo villa—a modernist house they nicknamed "The House Under a Crazy Star"—and hide them in the basement or the empty enclosures that once held lions and monkeys.

✨ Don't miss: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

How they didn't get caught

It's actually wild how they managed the day-to-day. You’ve got German soldiers literally stationed on the zoo grounds, yet there are up to 50 "guests" hiding in the house at any given time. Antonina was the tactical backbone here. She used music as a sophisticated alarm system.

- The Warning: If she saw Nazis approaching the villa, she’d sit at the piano and play Go, go to Crete! from Offenbach's operetta La Belle Hélène. That was the signal for everyone to vanish into the basement or tunnels.

- The All-Clear: A different tune meant they could come out and breathe.

They even used animal code names. If Jan told his son Ryszard to "feed the peacocks," he was talking about the humans hiding in the basement. One family was called "The Squirrels" because of their reddish hair. It sounds almost whimsical, but it was a survival mechanism. If a neighbor or a suspicious guard overheard a conversation about "feeding the squirrels," it sounded like normal zoo business.

Antonina and Jan Zabinski: More Than Just Zookeepers

People often paint Antonina as the "gentle" one and Jan as the "brave" one. That’s a bit of a disservice to both.

Antonina was a survivor long before the war. She lost her parents during the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and had this uncanny, almost supernatural ability to calm both animals and terrified humans. Jan later said she could talk to a "hungry lion" and make it back down. She had to use that same "animal whisperer" energy on SS officers.

Jan, on the other hand, was a hardcore pragmatist. He was an atheist who believed in the "biological right" to survive and the duty to protect one's species—humanity. He wasn't doing this for a religious reward; he did it because it was the only logical response to madness.

🔗 Read more: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

In 1944, things got even heavier. Jan fought in the Warsaw Uprising, got wounded, and was taken to a German prisoner-of-war camp. Antonina was left alone at the zoo with her young son and a newborn daughter, Teresa. She kept the rescue operation running by herself while the city around her was being burned to the ground.

The numbers that matter

- 300: The approximate number of Jews the Zabinskis saved.

- 2: The number of people hidden at the zoo who didn't survive the war (they were caught elsewhere after leaving the zoo).

- 1965: The year Yad Vashem recognized them as Righteous Among the Nations.

What the movie gets wrong (sorta)

The film The Zookeeper's Wife makes it look like a tense, romantic thriller. In reality, it was years of soul-crushing boredom mixed with sudden, heart-stopping terror. There wasn't always a dramatic escape. Sometimes it was just weeks of sitting in a dark basement, smelling like pig manure, hoping the floorboards wouldn't creak.

Also, the relationship with Lutz Heck was way more nuanced. He wasn't just a cartoon villain; he was a colleague who had turned into a monster through ideology. That personal betrayal added a layer of psychological stress that's hard to capture on screen.

Why this matters now

The story of Antonina and Jan Zabinski isn't just a history lesson. It’s a case study in "civil courage." Most people think they’d be the ones hiding neighbors in a crisis, but the Zabinskis actually did it when the law said they’d be executed for giving a thirsty person a glass of water.

After the war, Jan returned. They rebuilt the zoo. He wrote over 50 books. He eventually retired because he felt the new communist regime was suffocating his scientific freedom. They lived out their lives in Warsaw, relatively quiet heroes.

💡 You might also like: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

How to honor their legacy today

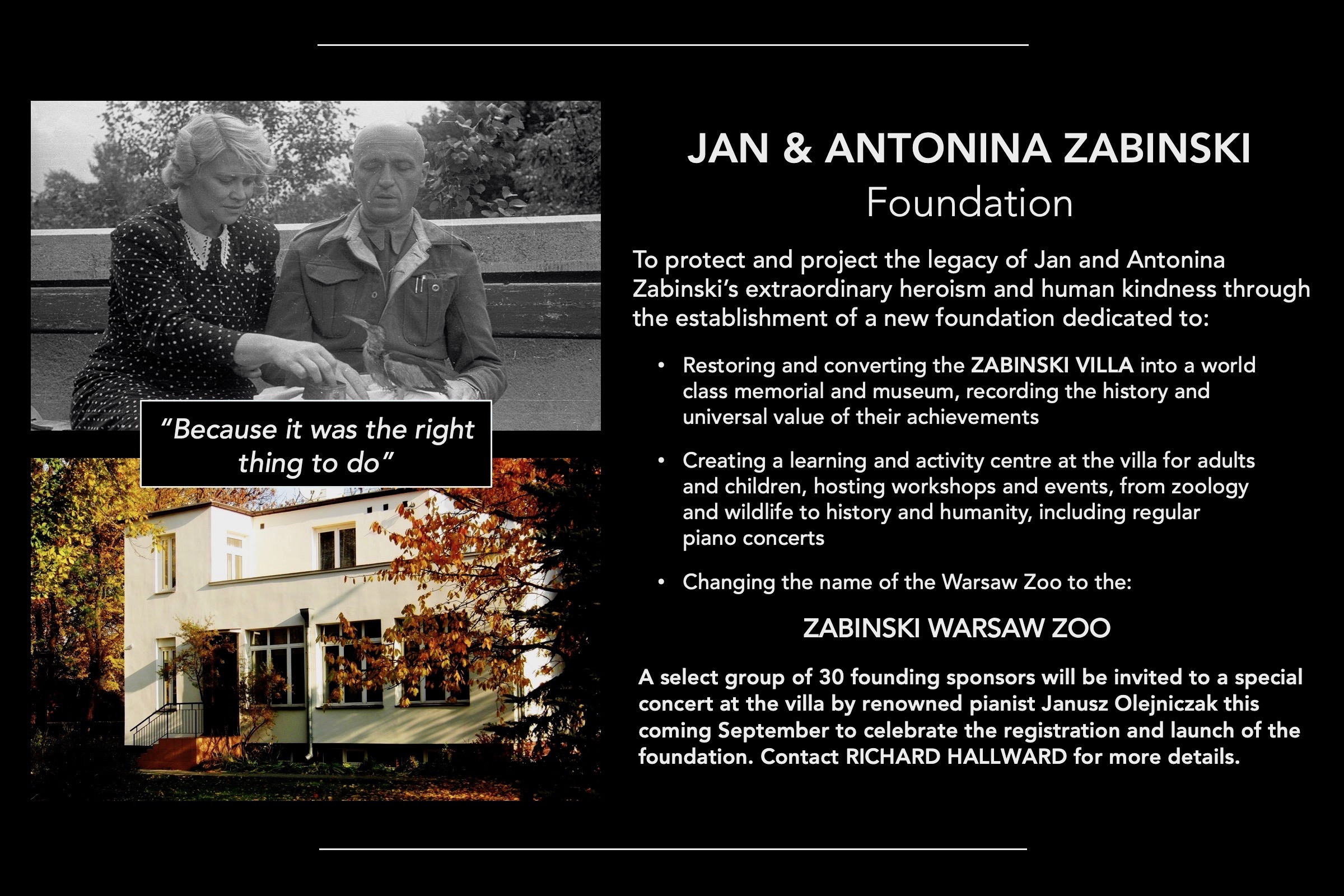

If you’re ever in Poland, you can actually visit the Zabinski Villa at the Warsaw Zoo. It’s been restored, and you can see the basement and the piano. But beyond tourism, there are real ways to apply their "Noah's Ark" mindset today:

- Support modern-day "Zegota" organizations: The Zabinskis worked with Zegota (the Council to Aid Jews). Today, organizations like the International Rescue Committee (IRC) or local refugee resettlement groups do the same ground-level work.

- Practice "Small Acts": Jan started by just bringing extra food into the Ghetto. It didn't start with a grand plan to save 300 people. It started with one person and one meal.

- Read the primary sources: Check out Antonina’s own memoirs (available in Polish as Ludzie i zwierzęta or "People and Animals"). It gives a much deeper look into her psyche than any secondary biography.

The Zabinskis didn't think they were extraordinary. Jan famously said he was just doing what any decent person should do. The fact that so few others did it is what makes their story stand out, but their blueprint for courage is something anyone can follow.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To truly grasp the scope of the Polish resistance, your next step should be researching the Zegota organization, the secret council that funded much of the Zabinskis' work. You can also explore the archives at Yad Vashem online to read the original testimonies of those who survived because of the "House Under a Crazy Star."