He doesn't have a backstory. He doesn't have a motive, at least not one that fits into a standard police report or a therapist's notebook. Anton Chigurh, played by Javier Bardem in the Coen Brothers’ 2007 masterpiece No Country for Old Men, isn't just a movie bad guy. He is a walking, breathing personification of catastrophe.

When Javier Bardem first took the role, he famously told the Coen brothers that he didn't drive, he didn't speak good English, and he hated violence. They told him that’s exactly why they wanted him. It worked. Bardem’s performance didn't just win him an Oscar; it created a new benchmark for cinematic dread.

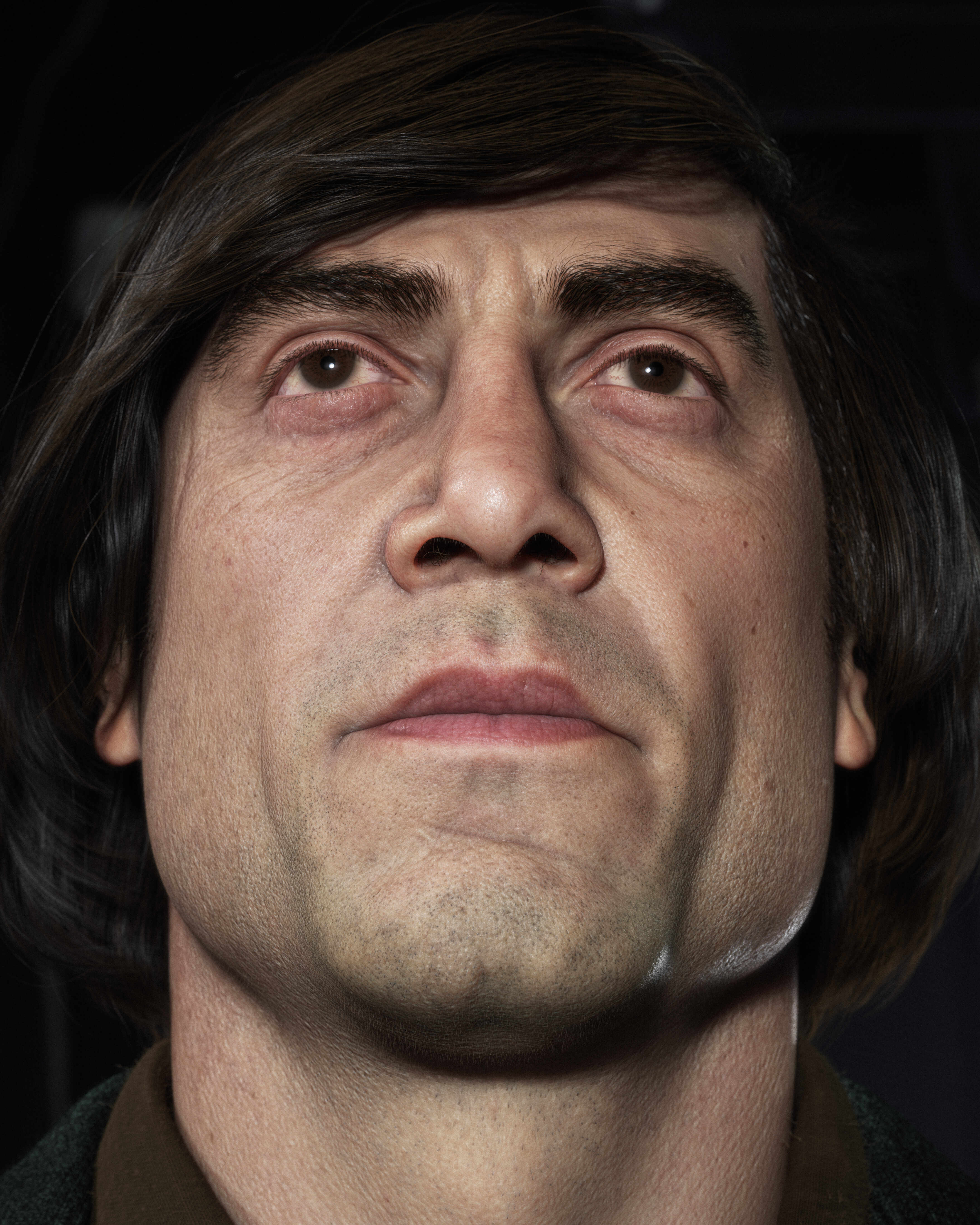

People still talk about that haircut. It’s ridiculous, right? A pageboy bob that looks like it belongs on a Victorian schoolgirl or maybe a member of the Monkees. But on Chigurh, it’s terrifying because it signals a complete lack of vanity. He doesn't care if he looks absurd. He is a ghost in a denim jacket, carrying a captive bolt pistol—a tool meant for slaughtering cattle—to execute people who just happen to be in his way.

The Philosophy of the Coin Toss

Most villains want something specific. Money. Power. Revenge.

Chigurh is different. While he is technically chasing a suitcase filled with $2 million, his true North Star is a rigid, terrifying sense of fate. You see this most clearly in the gas station scene, which is arguably one of the most tense five minutes in cinema history. He asks the clerk to "call it." The clerk has no idea what he's playing for. We, the audience, know he's playing for his life.

It’s not about the money. It’s about the fact that the clerk "married into" the gas station. To Chigurh, the man’s entire life has led to this specific moment of intersection. The coin is just the instrument of a universe that doesn't care if you're a good person or a bad one.

Psychologists have actually studied this. In a 2014 study published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences, a team of psychiatrists scanned hundreds of movies to find the most "real" depiction of a psychopath. They landed on Chigurh. They noted his "incapacity for love," lack of remorse, and lack of any recognizable emotional life. He isn't "crazy" in the way Hollywood usually does it. He’s just... empty.

Bardem’s Physicality and the Silence of the Desert

Watch how Javier Bardem moves. He’s heavy. He walks with a deliberate, slow thud. In the scenes where he’s tracking Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), he barely speaks. The Coens stripped away the soundtrack for most of the film, replacing it with the sound of wind, the crinkle of a candy wrapper, or the beep of a transponder.

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

This silence makes Chigurh feel inevitable.

There’s a moment where he sits on a couch, drinking milk, watching his own reflection in a dead television screen. It’s eerie. It feels like he’s a predator who has completely mastered the art of waiting. Bardem used a very specific breathing technique for the role—shallow and nasal—which makes him sound like he’s constantly on the verge of a hunt.

Why He Wins (And Why That Upsets Us)

In a typical Western, the lawman catches the outlaw. Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, played by Tommy Lee Jones, is the moral center of the story, but he’s outmatched. Not because he’s weak, but because he’s human. He belongs to a world of rules. Chigurh belongs to a world of chaos.

The movie deviates from the "good guy wins" trope in a way that feels like a punch to the gut. When Chigurh finally confronts Carla Jean Moss, Llewelyn’s wife, she refuses to call the coin toss. She tells him, "The coin don't have no say. It’s just you."

She’s right.

But it doesn't matter. He kills her anyway.

This is the "No Country" part of the title. The world has changed into something unrecognizable where men like Chigurh can't be stopped by traditional justice. He is a force of nature. You don't arrest a hurricane. You just survive it, or you don't.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

The Captive Bolt Pistol as a Symbol

Why the cattle gun? Aside from being incredibly quiet—which is practical for a hitman—it’s a symbolic choice. It treats human beings like livestock. In Chigurh’s eyes, there is no difference between a man and a steer at the packing plant. Both are just biological matter waiting for the end.

The sound design of that weapon is haunting. It’s a mechanical thwip-hiss. It’s clinical. No gunpowder, no passion. Just a hole where a brain used to be. It reinforces the idea that Chigurh isn't a "killer" in the passionate sense. He’s an exterminator.

The Real-World Impact of Javier Bardem’s Performance

Before this movie, Bardem was known primarily in international cinema for romantic or intense dramatic roles in films like Before Night Falls. He was a sex symbol.

No Country for Old Men changed his career trajectory. It proved he could disappear so deeply into a repulsive character that the audience forgets the actor exists. Since then, we’ve seen him play other villains, like Raoul Silva in Skyfall, but none have the staying power of Chigurh.

Why? Because Silva had a grudge. Grudges are relatable. Chigurh has a philosophy.

If you look at the landscape of modern thrillers, you can see the Chigurh "blueprint" everywhere. Characters who don't explain themselves. Villains who operate on a moral plane that is entirely alien to our own. But no one has quite captured that specific mix of the mundane and the monstrous that Bardem brought to the screen.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

Some viewers feel cheated by the ending because we don't see Chigurh "get what's coming to him." He gets in a car accident, yes. His bone is sticking out of his arm. He’s hurt.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

But he limps away.

He buys a shirt off a kid to make a sling and disappears into the suburbs. This isn't a mistake. It’s the point. Evil isn't always vanquished. Sometimes it just moves to the next town. It survives through sheer, cold-blooded persistence.

How to Watch It Now

If you’re revisiting the film, don't just watch Bardem’s face. Watch his hands.

Notice how he handles objects. The way he meticulously removes his boots so he won't make noise on a floorboard. The way he checks the bottom of his shoes after a killing to make sure he hasn't tracked blood. This level of detail is what makes the character feel "human-quality" in its terror. It’s not a cartoon. It’s a man who has optimized his life for the delivery of death.

Actionable Insights for Cinephiles:

- Read the book: Cormac McCarthy’s prose is sparse and provides even more insight into Chigurh’s internal "logic," which is even darker than the film depicts.

- Watch the "Gas Station" scene with the sound off: You’ll notice how Bardem uses micro-expressions to dominate the space without saying a word.

- Study the "Rule of Three" in his killings: He often gives victims three chances—either through dialogue or the coin—to change their fate, even if they don't realize they're being tested.

The legacy of Anton Chigurh isn't just about a scary guy in a movie. It’s about the realization that the world is a lot more random and a lot less fair than we’d like to believe. Javier Bardem didn't just play a villain; he gave us a mirror to our own deepest fears about the lack of control we have over our lives.

Chigurh is still out there, metaphorically speaking. He’s the car that runs a red light. He’s the sudden illness. He is the coin flip that comes up tails when you needed heads. That is why, nearly two decades later, we are still talking about him.