It isn’t just about the food. Honestly, that’s the first thing anyone needs to understand before diving into the clinical weeds of the anorexia nervosa dsm 5 criteria. For years, the public image of this disorder was a very specific, very narrow caricature: a young, skeletal woman refusing a tray of food. But the American Psychiatric Association (APA) had to get a lot more nuanced when they updated the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to its fifth edition. They realized the old rules were actually keeping people from getting the help they desperately needed.

Diagnoses change because our understanding of the human brain evolves.

When the DSM-5 dropped, it replaced the older DSM-IV-TR, and the shifts were seismic, even if they looked like small wording tweaks on paper. The goal was simple: make it easier to catch the disorder early. Because waiting until someone is at death's door to "qualify" for a diagnosis is a failing grade for the medical community.

The Three Pillars of Anorexia Nervosa DSM 5

To get an official diagnosis under the current guidelines, a person has to check three specific boxes. It sounds clinical, but the reality behind these checkboxes is often a chaotic, internal nightmare.

First, there’s the restriction of energy intake. This is the one everyone knows. It’s about eating significantly less than the body requires to function, leading to a body weight that is lower than the minimally normal level for that person’s age, sex, and physical health. But here is where it gets interesting—the DSM-5 removed the "refusal" language. The old version said a patient "refused" to maintain weight. The new version focuses on the behavior of restriction. It’s a subtle shift from judging a person’s will to observing their actions.

Second, there is an intense fear of gaining weight. It’s not just "I’d rather be thin." It is a paralyzing, phobic-level terror of becoming "fat," even if the person is already significantly underweight. This fear doesn't usually go away when the weight drops. Often, it gets louder.

Third, we have the body image distortion. This is technically called "disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced." Basically, when they look in the mirror, the reflection they see isn't reality. Or, they place an unhealthy amount of their self-worth on their scale number.

Why the "Missing Period" Rule Had to Go

One of the biggest wins for the anorexia nervosa dsm 5 update was the removal of amenorrhea.

For decades, if you were a woman and you still had your period, you couldn't "officially" be diagnosed with anorexia. You were stuck in the "Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified" (EDNOS) basement. This was a massive problem. It excluded men. It excluded women on certain types of birth control. It excluded prepubescent girls and postmenopausal women.

By nixing the requirement for three missed menstrual cycles, the APA acknowledged that the psychological and behavioral patterns of anorexia are what define the illness, not just a specific hormonal side effect. It opened the door for a much more inclusive understanding of who actually suffers from this.

✨ Don't miss: National Breast Cancer Awareness Month and the Dates That Actually Matter

Subtypes: Restricting vs. Binge-Eating/Purging

Not every case of anorexia looks the same. The DSM-5 breaks it down into two main flavors.

The Restricting Type is what most people picture. In the last three months, the person has lost weight solely through dieting, fasting, or excessive exercise. There’s no regular purging or bingeing involved. It’s a rigid, iron-willed control over every calorie.

Then there is the Binge-Eating/Purging Type. This one is frequently confused with bulimia, but the distinction is the weight. If a person meets the low-weight criteria but also engages in episodes of binge eating or purging (like self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives), they fall under this category. It’s a cycle of intense restriction punctuated by moments where the dam breaks.

The Severity Scale: It's Not Just a Number

In the past, doctors just looked at Body Mass Index (BMI). While BMI is still used in the anorexia nervosa dsm 5 to gauge severity, clinicians are now encouraged to look at the whole person.

The current guidelines suggest these BMI markers for adults:

- Mild: BMI ≥ 17

- Moderate: BMI 16–16.99

- Severe: BMI 15–15.99

- Extreme: BMI < 15

But honestly? These numbers can be misleading. A person with a BMI of 18 who has lost 50 pounds in two months might be in more immediate medical danger than someone who has been at a BMI of 16 for years. The DSM-5 allows for "clinical judgment," which is a fancy way of saying doctors should use their heads and look at the rate of weight loss and the physical toll on the body.

Atypical Anorexia: The Invisible Struggle

We have to talk about "Atypical Anorexia Nervosa." This falls under the umbrella of Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED).

Someone with atypical anorexia meets all the criteria for anorexia—the restriction, the intense fear, the distorted body image—but their weight is within or even above the "normal" range. This happens a lot. Maybe they started at a higher weight and have lost a massive amount very quickly.

The health risks are just as real. The heart doesn't care what your BMI is if you are starving it of electrolytes and fuel. People with atypical anorexia often face more stigma because they don't "look" like they have an eating disorder, which makes the DSM-5's recognition of this category so vital.

🔗 Read more: Mayo Clinic: What Most People Get Wrong About the Best Hospital in the World

The Physical Toll Nobody Likes to Discuss

Anorexia is the deadliest mental health disorder. Period.

It isn't just about being thin; it's about the body literally consuming itself to stay alive. When the "anorexia nervosa dsm 5" criteria are met, the heart muscle starts to thin out. This leads to bradycardia (a dangerously slow heart rate) and hypotension.

Bone density plummets. This is often irreversible, leading to osteoporosis in people who aren't even 25 yet. The brain actually shrinks. Gray matter volume decreases because the brain is largely made of fat and requires massive amounts of energy to function. When that energy stops coming in, the brain prioritizes basic survival over complex emotional regulation or logical thinking.

Then there’s the "lanugo." It’s a fine, downy hair that grows all over the body—the face, the back, the arms. It’s the body’s desperate attempt to insulate itself because there’s no body fat left to keep the internal organs warm.

Beyond the Criteria: The Genetic and Environmental Mix

Why do some people develop this while others can diet and just... stop?

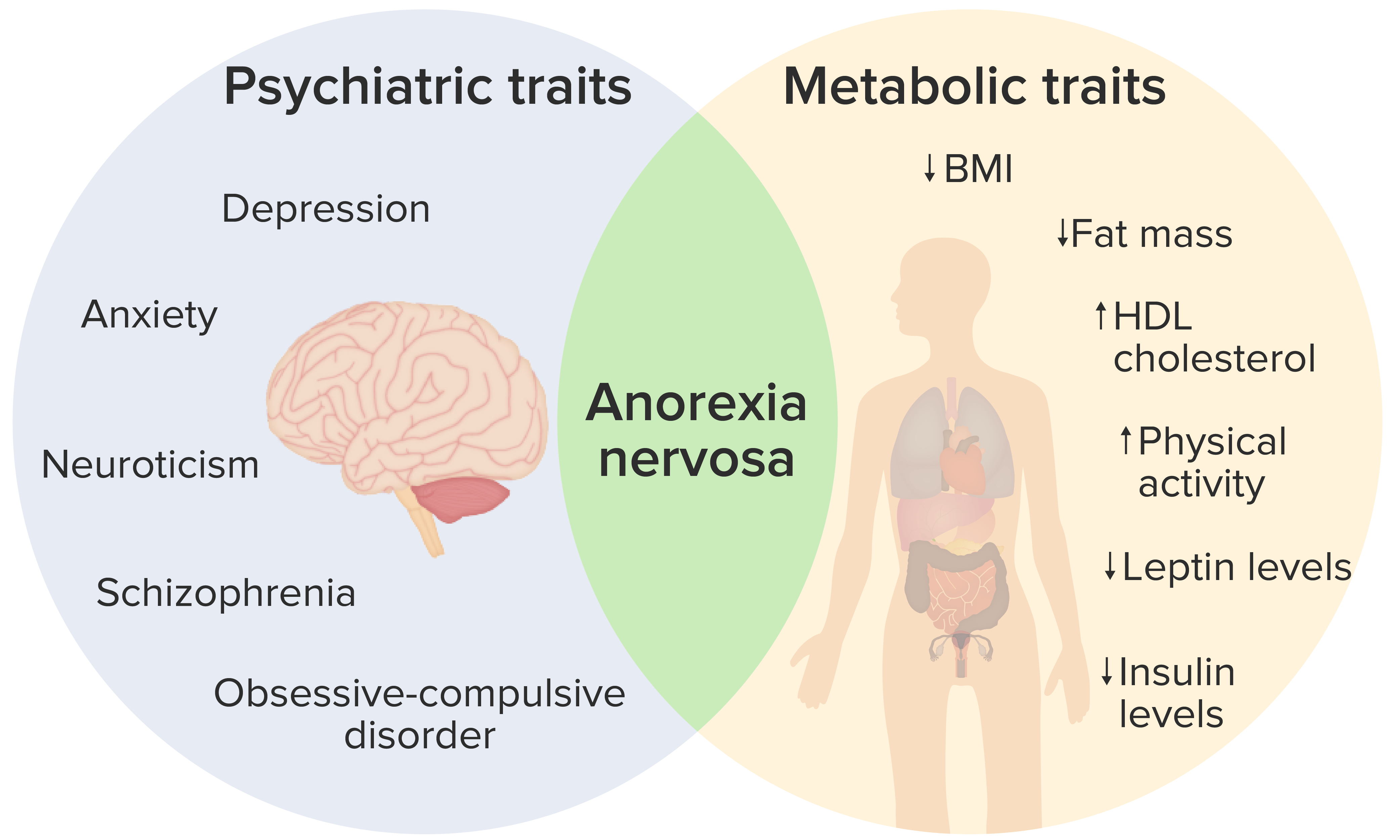

Research, including landmark studies by Dr. Cynthia Bulik at the University of North Carolina, suggests a strong genetic component. It’s not just a "socially driven" illness caused by Instagram filters or fashion magazines. Those things are triggers, sure, but the underlying biology is often pre-loaded.

People with anorexia often share certain personality traits: perfectionism, high anxiety, and "harm avoidance." Their brains may actually process reward differently. For most people, eating is a reward. For someone with anorexia, the act of not eating or losing weight provides the dopamine hit, while eating can trigger intense anxiety.

Assessing the Limitations

No diagnostic manual is perfect. The DSM-5 has been criticized for still being too tied to weight as a primary marker. Many experts argue that the psychological distress should carry more weight than the physical symptoms.

Also, the "intense fear of weight gain" criterion can be tricky. Some patients, especially in different cultures or younger children, don't express a fear of "fatness." They might describe it as a fear of stomach pain, a general lack of appetite, or a sensory issue. If a clinician is too rigid with the anorexia nervosa dsm 5 wording, they might miss these "non-fat-phobic" cases.

💡 You might also like: Jackson General Hospital of Jackson TN: The Truth About Navigating West Tennessee’s Medical Hub

Actionable Steps: What To Do Now

If you or someone you know is ticking these boxes, "waiting and seeing" is the worst strategy. Recovery is possible, but it requires a team.

1. Seek a specialized assessment.

Don't just go to a general practitioner. Find an eating disorder specialist or a therapist who understands the nuances of the DSM-5. General doctors often miss the early signs if the BMI isn't "low enough" yet.

2. Focus on "Medical Stabilization" first.

Before the deep-dive therapy can happen, the body has to be safe. This might mean blood work, EKGs, and a meal plan designed to prevent "refeeding syndrome"—a dangerous shift in electrolytes that can happen when someone starts eating again after a long period of starvation.

3. Move toward "Full Nutritional Rehabilitation."

This isn't just about eating more. It’s about restoring the brain’s ability to think clearly. You cannot "talk therapy" your way out of a starving brain. Weight restoration is the prerequisite for psychological healing.

4. Build a multidisciplinary team.

Ideally, you want a therapist (CBT or DBT focused), a registered dietitian (one who is "pro-recovery" and "anti-diet"), and a medical doctor. For minors, Family-Based Treatment (FBT), also known as the Maudsley Approach, is currently the gold standard.

5. Address the co-occurring issues.

Anorexia rarely travels alone. It usually brings friends like depression, OCD, or social anxiety. Treating the eating disorder without treating the underlying anxiety is like fixing a leaky pipe but ignoring the flood in the basement.

The anorexia nervosa dsm 5 criteria are a map, not the whole territory. They help doctors communicate and help insurance companies authorize treatment, but the human experience of the illness is far more complex than three bullet points. Early intervention is the single most important factor in long-term recovery. If the thoughts are there, if the restriction has started, the time to act is now.

Contact the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) or the Project HEAL foundation if you need help navigating the cost of treatment or finding providers in your area. They have databases specifically designed to match patients with the level of care they actually need, regardless of where they fall on the severity scale.

The path back to a normal relationship with food is long and rarely a straight line. It involves a lot of "two steps forward, one step back." But with the right diagnostic lens and a dedicated support system, the brain can rewire itself, and the body can heal. Don't let a "normal" BMI fool you into thinking everything is fine. If the mental criteria are met, the struggle is real and deserves professional attention.

To begin the process of finding specialized care, start by documenting specific behavioral patterns—not just weight changes—to provide a clearer picture to your healthcare provider. This ensures the diagnosis is based on the full scope of the disorder rather than a snapshot of a single metric.