History has a nasty habit of turning real women into ghosts. Usually, when we talk about Annie Chapman, she’s just a name in a sequence. Victim number two. A data point in the "Canonical Five" of the Jack the Ripper saga.

But Annie wasn’t a ghost. Honestly, she was a woman who had a pretty decent life for a long time before things fell apart. People often picture these victims as career street-walkers who lived in the gutter from birth. That’s just not true.

📖 Related: The Shooting in Petaluma Today: What We Actually Know So Far

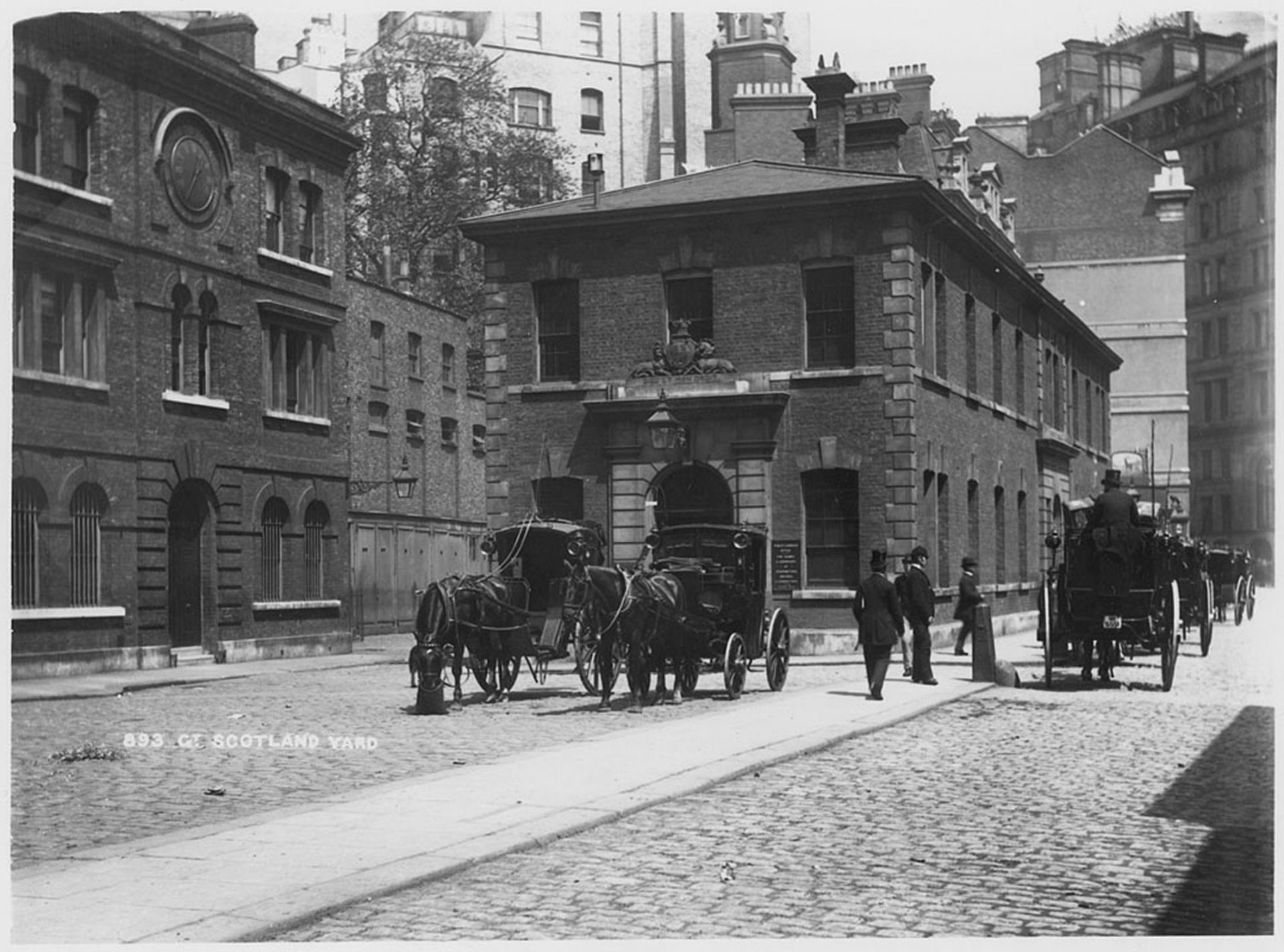

Annie Eliza Smith was born in Paddington in 1840. Her father was a soldier—a Lifeguard, actually—and she grew up in a world of military discipline and respectable domestic service. When she married John Chapman, a coachman, in 1869, she was set. They had a home. They had kids. They lived in Windsor and West London, far from the smog and misery of Spitalfields.

So how does a woman go from living in a coachman’s house in Windsor to dying in a backyard at 29 Hanbury Street?

It wasn’t a sudden drop. It was a slow, agonizing slide.

The Tragedy Behind the "Dark Annie" Moniker

By the time she reached Whitechapel, people called her "Dark Annie." It sounds like a name from a noir novel, but it just referred to her wavy, dark brown hair and blue eyes.

The real tragedy of Annie Chapman is that she was a mother who lost her world. She had three children. Her eldest, Emily Ruth, died of meningitis when she was only 12. Her youngest son, John, was born with a disability. This kind of grief breaks people.

Both Annie and her husband turned to the bottle. Alcoholism in the Victorian era wasn't treated; it was just a moral failing that ruined families. By 1884, the marriage was dead. They separated by "mutual consent," and John agreed to pay her ten shillings a week.

That ten shillings was her lifeline.

As long as that money arrived by Post Office Order, Annie could survive in the lodging houses without selling her body. She sold crochet work. She made artificial flowers. She tried, she really did. But then, on Christmas Day in 1886, John Chapman died of cirrhosis.

The money stopped. That was the end of Annie’s "respectable" life.

Why 29 Hanbury Street Changed Everything

The murder of Annie Chapman on September 8, 1888, was the moment London truly panicked. Mary Ann Nichols had been killed a week earlier, but Annie’s death was different. It was more surgical. More daring.

She was killed in the backyard of a house packed with people. Seventeen people lived at 29 Hanbury Street. Someone, a resident named John Davis, walked out the back door at 6:00 am to get a drink of water or head to work—and he saw her.

She was lying near the stone steps.

The details from the autopsy by Dr. George Bagster Phillips are stomach-churning. Her throat was cut so deeply it nearly severed the head. But what really set the press on fire was the removal of her uterus. The killer didn't just kill her; he performed a frantic, skilled extraction in the dark, within earshot of sleeping families.

The Shabby Genteel Man

We actually have a decent idea of what happened in the hours before. Around 5:30 am, a witness named Elizabeth Long saw Annie talking to a man outside number 29.

She described him as "shabby genteel." Basically, he looked like a man who had fallen on hard times but was still wearing a dark overcoat and a deerstalker hat. He was about forty.

"Will you?" he asked.

💡 You might also like: Iran Missiles Attack Israel: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

"Yes," Annie replied.

Those were likely her last words. Ten minutes later, a neighbor heard a faint "No" and a thump against the fence. By 6:00 am, she was gone.

What the Ripper Investigators Missed

The police were obsessed with a character called "Leather Apron"—a local Jewish bootmaker named John Pizer. They arrested him because he had a reputation for being mean to prostitutes, but he had ironclad alibis.

The problem was that the police were looking for a monster, but they were likely dealing with someone who could blend in. Annie wasn't a fool. She was described as intelligent and "very civil" when sober. If she went into that backyard with this man, it’s because he didn't look like a threat.

He looked like a customer.

Also, Annie was dying anyway. The autopsy revealed she had advanced tuberculosis (consumption) and brain disease. She told a friend, Amelia Palmer, just days before her death that she felt "too ill to do anything." She was weak, she had a black eye from a fight with another woman over a bar of soap, and she was desperate for fourpence to pay for a bed.

Basically, the "Ripper" didn't just take her life—he took what little time she had left.

Why the Annie Chapman Case Still Matters

If you want to understand the Victorian underclass, don't look at the statistics. Look at Annie.

👉 See also: Kamala Harris: What Most People Get Wrong About Her Future

Her life shows how thin the line was between middle-class security and the "casual ward" of the workhouse. One death in the family—her daughter or her husband—and the whole house of cards collapsed.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're researching the Whitechapel murders or visiting London, keep these things in mind about Annie’s story:

- Visit the Site (Virtually or Physically): 29 Hanbury Street no longer exists as it was; it’s part of a brewery site now, but the geography of the "backyard" layout explains how the killer escaped.

- Read the Inquest Records: Don't rely on sensationalist books. Read the actual testimonies of Elizabeth Long and Dr. Phillips. They provide the most grounded view of the timeline.

- Focus on the Social Context: Annie’s struggle with the "Post Office Order" system and the lodging house "deputies" tells you more about 1888 than any conspiracy theory about royal doctors.

- Check the Manor Park Cemetery: Annie is buried there in a public grave. There is a plaque now. It’s a somber reminder that she was a person, not a prop for a horror movie.

Annie Chapman’s death forced the "West End" of London to finally look at the "East End." The press used her murder to bash the police and the government for the horrific living conditions in Spitalfields. She became a symbol of the "unfortunate" class, but to her brother Fountain Smith and her surviving children, she was just a sister and a mother who couldn't find her way back home.

The mystery of who killed her might never be solved. But the mystery of who she was is right there in the records, waiting to be remembered properly.

To truly understand the era, look into the "Common Lodging Houses Act" of the time. It explains why women like Annie were forced onto the streets at 2:00 am if they couldn't produce a few pennies. Understanding the law of the street is the only way to understand why Annie ended up in that backyard.