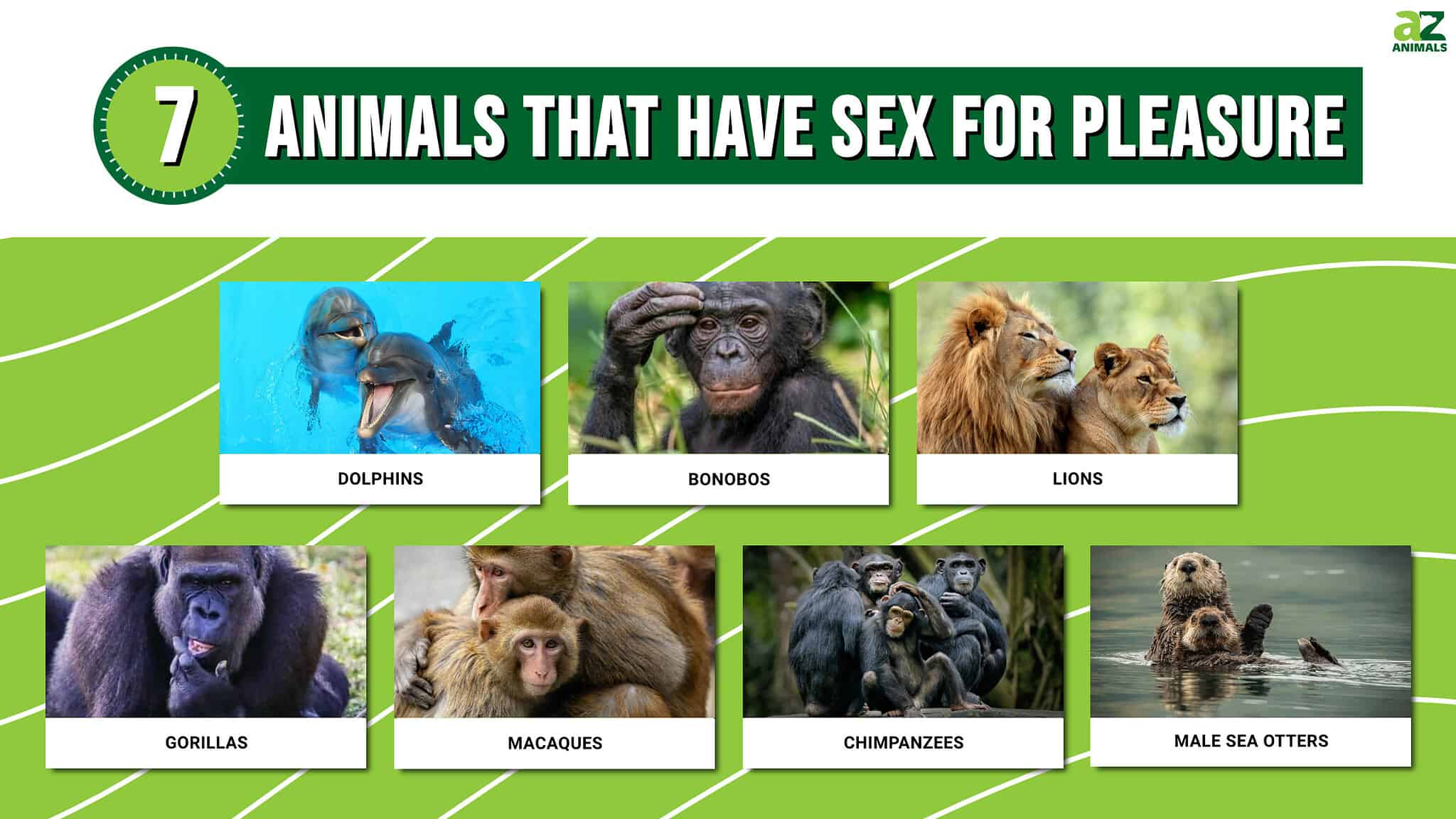

Nature is messy. If you grew up watching nature documentaries where everything is a neat cycle of "the male does a dance, the female accepts, and they make a baby," you’ve been sold a sanitized version of reality. In the wild, animals have sex with animals for reasons that have absolutely nothing to do with making babies. It’s chaotic. It’s often confusing to human observers. Honestly, it’s a lot more like human behavior than most scientists were willing to admit until a few decades ago.

For a long time, researchers just ignored the "weird" stuff. They called it "biological errors" or "hormonal glitches." But when you look at the sheer volume of non-reproductive sexual behavior across the animal kingdom, you realize it isn't a glitch. It’s a feature. From social bonding to stress relief, the reasons behind these interactions are as complex as any human relationship.

The Bonobo Handshake and Social Glue

Take the bonobo. These great apes are our closest relatives, alongside chimpanzees, but they have a totally different way of handling stress. While chimps might go to war, bonobos have sex. It’s their primary way of saying "sorry" or "let's be friends." In bonobo society, animals have sex with animals regardless of age, gender, or even social standing.

They use sexual contact to resolve conflicts over food or territory. If two females are eyeing the same piece of fruit, they might engage in "GG-rubbing" (genito-genital rubbing) to lower the tension before sharing the meal. It isn’t about reproduction; it’s about social lubrication. Dr. Frans de Waal, a primatologist who spent decades studying them, famously noted that bonobos use sex like we use a handshake.

It’s a powerful survival strategy. By reducing internal friction within the group, the community stays tighter. They protect each other better. They share resources more effectively. In this context, sex is a tool for peace.

🔗 Read more: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Do Different Species Mate?

This is where it gets truly bizarre. Interspecies mating—where animals have sex with animals from a completely different branch of the tree of life—happens more often than you’d think. Sometimes there’s a biological "logic" to it, like the creation of hybrids (think ligers or mules), but other times, it’s just baffling.

You’ve probably seen the viral videos of seals and penguins. It sounds like a joke, but researchers in South Africa documented multiple instances of Antarctic fur seals attempting to mate with king penguins. This isn't "love." Most biologists, like those who published the study in the journal Polar Biology, suggest it’s likely a learned behavior or a result of sexual frustration. Younger seals, unable to compete for female seals, may redirect those urges toward the most available warm-blooded creature nearby.

Then you have the "misidentification" factor. Some species have such similar mating signals that things get crossed. Certain types of beetles have been caught trying to mate with discarded beer bottles because the brown, dimpled glass looks—to a beetle—like the perfect female. Nature isn't perfect. It's built on "good enough" recognition systems.

Same-Sex Partnerships in the Wild

We can’t talk about how animals have sex with animals without mentioning that same-sex behavior has been observed in over 1,500 species. This isn't a "modern" phenomenon or something caused by captivity. It’s everywhere.

💡 You might also like: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

- Laysan Albatrosses: On the island of Oahu, roughly 31% of the nesting pairs are actually female-female couples. They court, they bond for life, and they even raise chicks together (often sired by a "sneaky" male from a different pair). These pairs are better at raising young than a single female would be.

- Giraffes: Male giraffes spend a staggering amount of time "necking"—a ritual that involves rubbing necks together—which often leads to mounting. In some populations, more than 90% of observed sexual activity happens between males.

- Bottlenose Dolphins: These are the hedonists of the ocean. Male dolphins form intense "alliances" that can last a lifetime. They engage in frequent sexual play with each other to cement these bonds. For dolphins, sex is a social language.

The Role of Pleasure and Play

One of the biggest hurdles in biology was admitting that animals might do things just because it feels good. We like to think of animals as biological robots driven purely by the instinct to survive. But the brain’s reward system—dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin—isn't exclusive to humans.

When animals have sex with animals outside of their fertile windows, or with members of the same sex, or even with different species, they are often responding to the same neurochemical rewards we do. Juvenile animals, especially mammals, engage in sexual play as a form of practice. It’s a way to learn the physical mechanics and social nuances of their species before the stakes are high.

Sheep are a fascinating example. About 8% of domestic rams show a lifelong preference for other rams, even when fertile ewes are available. This isn't a phase or a choice; it’s a hardwired neurological preference. Research at Oregon Health & Science University found distinct differences in the "sheep sexually dimorphic nucleus" in the brain, proving that these preferences have a deep biological basis.

The Evolutionary "Why"

If it doesn't make a baby, why does evolution allow it? Why hasn't it been "weeded out"?

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

The answer lies in the "Social Glue Hypothesis." Evolution doesn't just select for the individual; it often selects for the group. If a certain behavior—even a non-reproductive one—makes a group more stable, less violent, or better at raising orphaned young, then the genes that allow for that behavior will persist.

Also, evolution is rarely "clean." Many traits are "spandrels"—byproducts of other useful traits. The high sex drive required to ensure an animal reproduces might be so strong that it spills over into other areas. If a high-drive male reproduces more often, his "extra" energy spent on non-reproductive sex doesn't hurt his fitness enough for nature to get rid of it.

Practical Insights and Nuance

Understanding that animals have sex with animals for non-reproductive reasons changes how we view conservation and animal welfare.

- Stop Anthropomorphizing: While it’s tempting to call an albatross pair "lesbian" or a seal "aggressive," these are human labels. Animals operate on their own sets of biological and social rules.

- Captivity Matters: Sometimes, unusual sexual behavior in zoos is a sign of stress or a lack of enrichment. However, just as often, it’s totally normal behavior that keepers are only now starting to document without bias.

- Diversity is the Rule: If you see an animal doing something that doesn't "make sense" for reproduction, look for the social or chemical benefit. Is it reducing tension? Is it building an alliance?

The next time you hear someone say that certain behaviors are "unnatural," remind them of the bonobos, the albatrosses, and the dolphins. Nature isn't a strict rulebook; it's a sprawling, experimental lab where if it works—or even if it just doesn't hurt—it stays.

To truly understand animal behavior, we have to look past the "breeding" obsession. Start observing wildlife with a focus on social dynamics rather than just life cycles. Read field notes from ethologists like Jane Goodall or Marlene Zuk, who challenge the traditional narratives of "natural" behavior. The reality of how animals interact is far more diverse and fascinating than the simplified versions we were taught in school. Focus on the data, watch the social bonds, and accept that nature is rarely as simple as we want it to be.