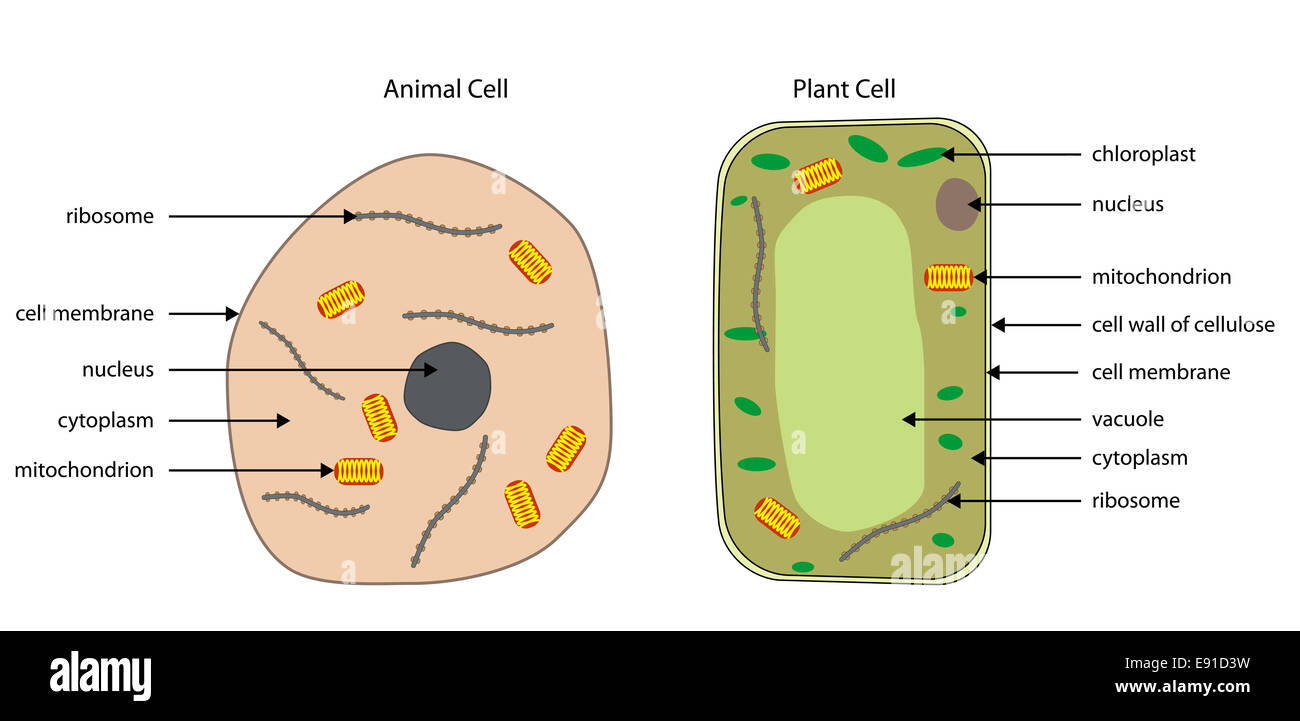

You’ve seen the diagram. It’s usually a bright green rectangle next to a squishy-looking pink blob. In every middle school science classroom, the animal and plant cell labeled poster hangs on the wall, looking like a cross between a circuit board and a bowl of soup. But here’s the thing: cells don't actually look like that. Not really. Those diagrams are "idealized" versions, simplified so our brains don't melt when we look at the chaotic, crowded reality of microscopic life. Honestly, if you saw a real cell without the helpful labels, you might just see a mess of gray fuzz and vibrating grains.

Biology is messy. It’s crowded. Inside your body right now, trillions of these tiny machines are chugging along, hitting speeds and efficiencies that make our best supercomputers look like abacuses. When we talk about an animal and plant cell labeled, we aren't just naming parts; we're mapping out the distinct strategies life uses to survive. Plants want to stand tall and eat sunlight. Animals want to move, eat, and respond. These different "lifestyles" dictate exactly what you find under the microscope.

The Architectural Divide: Walls vs. Fluidity

The biggest giveaway when looking at an animal and plant cell labeled is the boundary. Plant cells are basically tiny armored boxes. They have a rigid cell wall made of cellulose—the same stuff in your cotton t-shirts—which provides the structural integrity needed for a redwood tree to grow hundreds of feet tall without a skeleton. Animal cells? They’re different. They’re soft. They have a flexible plasma membrane that allows them to wiggle, crawl, and form complex shapes like neurons or muscle fibers.

Think of it like this. A plant cell is a brick house. An animal cell is a sturdy balloon filled with gelatin.

Because animal cells lack that wall, they can do things plants can't, like engulfing food particles through phagocytosis. But this flexibility comes at a price. Without that wall, an animal cell is prone to popping if it takes in too much water. Plants solved this with turgor pressure. They pump their large central vacuoles full of water until the cell is "turgid" or stiff, pressing against the wall like an over-inflated tire. This is why your celery gets limp when it’s old; the cells have lost their internal water pressure, and the walls are sagging.

The Power Plants and the Solar Panels

Everyone remembers the "powerhouse of the cell." Yes, the mitochondria. Both animal and plant cells have them because both need to break down sugar into ATP. But the animal and plant cell labeled diagrams show a massive difference in how they get that sugar.

💡 You might also like: Dokumen pub: What Most People Get Wrong About This Site

Plants have chloroplasts. These are the green, bean-shaped organelles that perform the miracle of photosynthesis. Inside are stacks of thylakoids that look like green pancakes. These structures capture photons and turn them into chemical energy. Animals? We have to go find our energy. We eat the plants or eat the things that ate the plants. Because we don't make our own food, you will never find a chloroplast in a healthy animal cell.

Interestingly, scientists like Lynn Margulis championed the "Endosymbiotic Theory," which suggests these organelles were once free-living bacteria. Long ago, a larger cell basically swallowed a bacterium but didn't digest it. They formed a partnership. Eventually, that bacterium became the mitochondria (and in plants, the chloroplast). It’s wild to think that our energy source is essentially an ancient roommate that never moved out.

Why the Nucleus Isn't Just a "Brain"

We often label the nucleus as the "control center," but that’s a bit of a lazy metaphor. It’s more like a highly secured library containing the original blueprints for everything the cell needs to build. In an animal and plant cell labeled diagram, the nucleus is usually that big sphere in the middle. Inside, the DNA isn't just floating around like spaghetti; it's meticulously coiled around proteins called histones.

If you stretched out the DNA from a single human cell, it would be about two meters long. Fitting that into a nucleus that is only 6 micrometers wide is a feat of engineering that puts the best luggage-packers to shame.

Rough ER and the Protein Factory

Right outside the nucleus sits the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER). In a labeled diagram, you’ll see "Rough" and "Smooth" versions. The "Rough" ER is covered in ribosomes, making it look like it has a bad case of the measles. These ribosomes are the actual construction workers, translating genetic code into physical protein chains.

📖 Related: iPhone 16 Pink Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

Once those proteins are made, they head to the Golgi Apparatus. If the ER is the factory, the Golgi is the shipping and receiving department. It modifies, sorts, and packages proteins into vesicles—tiny bubbles of membrane—to be sent where they’re needed. Sometimes they go to the cell surface to be "exported" (like hormones), and sometimes they stay inside to repair damage.

The Small Things People Forget to Label

When people look for an animal and plant cell labeled, they focus on the big stuff: Nucleus, Mitochondria, Vacuole. But the "minor" players are just as cool. Take the cytoskeleton. It’s a network of protein filaments—microtubules and actin—that acts as both a scaffold and a highway system.

Motor proteins like kinesin actually "walk" along these microtubule tracks, dragging massive vesicles behind them like tiny pack mules. It looks incredibly intentional, almost like a cartoon, but it's all driven by chemistry and thermal fluctuations.

- Centrioles: Usually only found in animal cells. They look like bundles of pasta and help organize cell division.

- Lysosomes: These are the recycling bins. They contain acid and enzymes to break down waste. While plants have similar structures in their vacuoles, true lysosomes are mostly an animal cell thing.

- Plasmodesmata: These are tiny holes in plant cell walls. Since the wall is so thick, plants need these "tunnels" so they can trade nutrients and signals with their neighbors.

Real-World Nuance: When Biology Breaks the Rules

Nature doesn't always follow the animal and plant cell labeled charts. Biology loves an exception. For instance, some "lower" plants like mosses and ferns actually have sperm cells with flagella—the little tails we usually associate with animal cells.

Then there are the fungal cells. Are they plants? No. Are they animals? No. They have cell walls like plants, but those walls are made of chitin (the stuff in shrimp shells), not cellulose. And like us, they have to "eat" other things to survive. They’re a weird, beautiful middle ground that reminds us that human categories are often a bit too rigid for the messy reality of the natural world.

👉 See also: The Singularity Is Near: Why Ray Kurzweil’s Predictions Still Mess With Our Heads

The complexity of these tiny units is staggering. A single cell contains millions of molecules, all interacting at lightning speed. It isn’t a static diagram. It’s a riot.

Moving Beyond the Diagram

Understanding the animal and plant cell labeled is the first step toward understanding how life actually functions on a grand scale. If you're studying this for an exam or just curious, don't just memorize the names. Think about the "why." Why does the plant need that wall? Because it can’t run away from a predator or walk to a water source, so it has to be tough. Why does the animal cell need lysosomes? Because we eat complex organic matter that needs to be aggressively broken down.

To truly grasp cellular biology, try these specific actions:

- Use a Virtual Microscope: Sites like the University of Delaware’s "Virtual Microscope" let you see real micrographs. Compare them to your labeled diagrams to see how different the "ideal" is from the "real."

- Draw It From Memory: Don't just look. Draw an animal cell and a plant cell side-by-side. Use different colors for the organelles that are unique to each (like chloroplasts vs. centrioles).

- Check Out "The Inner Life of the Cell": Search for this Harvard animation. It shows the motor proteins and the cytoskeleton in motion. It changes how you view the "static" parts of a labeled diagram forever.

- Think in 3D: Remember that cells aren't flat circles on a page. They are 3D spheres, cubes, and stars. Imagine the nucleus suspended in the middle of a thick, crowded soup of organelles.

By looking past the labels and seeing the cells as living, breathing machines, the terminology starts to stick because it finally makes sense. You aren't just learning names; you’re learning how the world is built from the bottom up.