Ever looked at a diagram of a cell and thought it looked like a neat little fried egg or a perfectly rectangular brick? Most of us have. But honestly, those animal and plant cell images we see in middle school are mostly lies. Well, maybe not lies, but massive oversimplifications. Real life is messy. Real cells are crowded, pulsating, and rarely look like the neon-colored drawings you find on a poster.

If you’re hunting for high-quality animal and plant cell images for a project or just because you’re a nerd for microscopy, you need to know what you’re actually looking at. Most people struggle to tell the difference once you strip away the bright green and pink labels.

The Problem With Modern Visuals

Biology is visual. We need to see things to get them. But there is a huge gap between a "model" and a "micrograph." A model is a 3D render—shiny, spaced out, easy to read. A micrograph is a photo taken through a microscope. It’s often grainy, gray, and looks like a soup of static.

Scientists like Dr. David Goodsell have revolutionized how we see these tiny worlds. His watercolors of the cellular interior aren't just art; they’re based on atomic coordinates. He shows that the inside of a cell isn't empty space with a few floating beans (mitochondria). It’s packed. It's a traffic jam of proteins. When you look at animal and plant cell images today, you’re usually seeing a "de-cluttered" version so your brain doesn't explode.

What Really Separates the Two?

It’s not just about the shape. You’ve probably heard "plants are squares, animals are circles." That's a total myth. Some plant cells are elongated fibers; some animal cells, like those in your skin (epithelial cells), are packed into tight, hexagonal grids that look very "geometric."

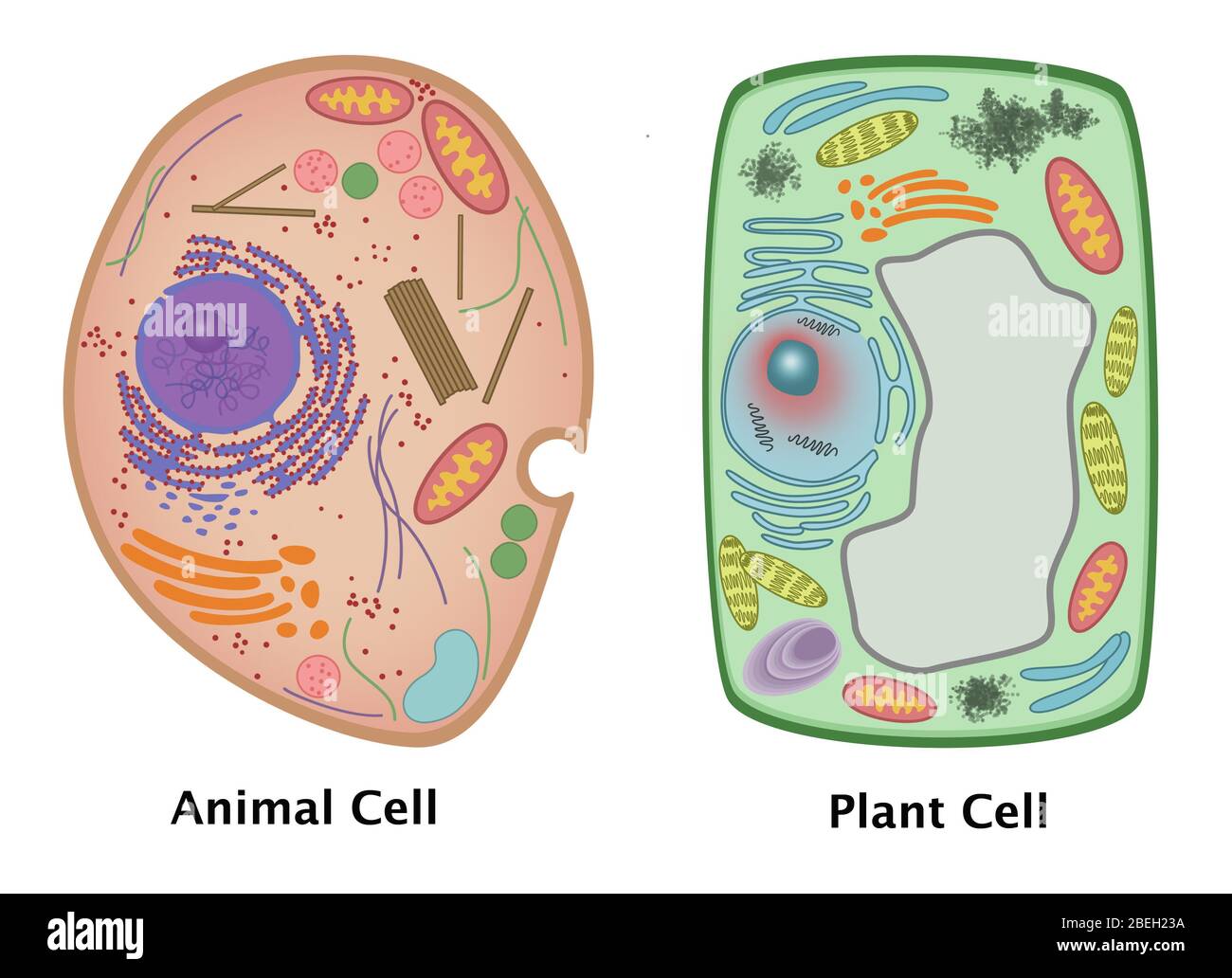

The real giveaway in any animal and plant cell images comes down to three specific structures.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

First, the cell wall. In plants, this is a rigid outer layer made of cellulose. It’s why trees stand tall without skeletons. Animals don't have this; we have "squishy" cell membranes. If you see a thick, defined border that looks like a frame, it’s a plant.

Second, the large central vacuole. In a plant, this is basically a huge water balloon that takes up 90% of the space, pushing everything else to the edges. Animal cells have vacuoles too, but they’re tiny and temporary.

Finally, chloroplasts. These are the green jellybeans. If the image shows little green discs, it’s a plant doing photosynthesis. Animals? We have to eat our lunch; we can't make it from sunlight.

The Hidden World of Organelles

Let's talk about the stuff both cells share. The nucleus is the big boss. It holds the DNA. In most animal and plant cell images, the nucleus is rendered as a large sphere. In reality, it has pores—nuclear pores—that act like bouncers, letting some molecules in and keeping others out.

Then there’s the mitochondria. The "powerhouse of the cell." (I know, I know, everyone says that). But did you know mitochondria have their own DNA? They actually look like bacteria because, billions of years ago, they probably were independent bacteria that got swallowed by a bigger cell and decided to stay. This theory is called endosymbiosis, championed by the legendary biologist Lynn Margulis.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Scale Matters

One thing animal and plant cell images often get wrong is the scale. They make the nucleus look huge and the ribosomes look like tiny dust motes. While that's somewhat true, the sheer number of ribosomes is staggering. A single human cell can have millions of them. They are protein-making machines. If you drew them to scale in a standard textbook image, the whole cell would just look like a blurry cloud of dots.

Where to Find High-Quality Imagery

If you're a student or a creator, don't just grab the first thing on Google Images. Most of those are low-res or biologically inaccurate.

- The Cell Image Library: This is a goldmine. It’s a public resource funded by the NIH. You can find actual RAW data from experiments. It’s not "pretty," but it’s real.

- Science Photo Library: These are the pros. They have colored scanning electron micrographs (SEMs) that make cells look like landscapes from another planet.

- Protein Data Bank (PDB): If you want to go deeper than the cell and see the molecules themselves, this is where the heavy lifting happens.

Practical Tips for Identification

Looking at a mystery slide?

- Check the border. Thick and crisp? Plant. Thin and wavy? Animal.

- Look for the "Water Balloon." If the center is a giant empty-looking void, it’s a plant vacuole.

- Spot the dots. Little green spots are chloroplasts (Plant). Centrioles (which look like little pasta noodles) are usually only in animal cells.

The Future of Cell Imaging

We’re moving past static pictures. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is the new king. It involves freezing samples so fast that the water doesn't even form crystals, preserving the cell in its natural state. This allows scientists to see the 3D structure of proteins in near-atomic detail. When you see modern animal and plant cell images that look incredibly sharp and 3D, they’re likely built from cryo-EM data.

Another cool tech is fluorescence microscopy. Scientists "tag" parts of the cell with glowing dyes. One part glows neon blue, another bright red. It’s not just for looks; it lets researchers watch a cell divide in real-time.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Common Misconceptions

People think cells are static. Like a house.

Actually, they're more like a busy city. The cytoskeleton is a network of tracks. Motor proteins like kinesin actually "walk" along these tracks, carrying cargo from one side of the cell to the other. It looks like a little two-legged robot. If you ever see an animation of a cell, look for the walkers.

Also, the "cytoplasm" isn't just water. It’s a thick, crowded gel. Imagine trying to swim through a pool filled with Jell-O and thousands of beach balls. That’s what it’s like inside a cell.

Taking Action: How to Use These Images

If you’re studying for an exam or designing a presentation, stop using the "fried egg" model.

- Compare and Contrast: Place a 3D render next to a real micrograph. It helps the brain bridge the gap between "theory" and "reality."

- Focus on Function: Don't just label parts. Ask why the plant cell is shaped like a box. (Hint: It’s for structural stacking).

- Use Credible Sources: Stick to university databases or scientific journals like Nature or Cell.

The world of animal and plant cell images is evolving. We are getting closer to seeing life as it actually happens, in all its crowded, messy, glowing glory. Don't settle for the oversimplified version. Look for the complexity. That’s where the real science lives.

Next Steps for Deep Learning:

Identify a specific organelle you're curious about—like the Golgi apparatus—and search for a "Scanning Electron Micrograph" of it specifically. Seeing the actual texture of these structures changes how you understand their function. If you're building a project, try to source at least one "fluorescent" image to show the dynamic nature of cellular life.