You're staring at a circle. Two lines—maybe they're secants, maybe tangents—shoot out from a single point somewhere in the "void" outside that circle. They cut through the arc like a pair of scissors. If you've ever felt like geometry was just a series of hoops to jump through, you aren't alone. But angles outside of a circle are actually one of those weirdly elegant pieces of math that show up in everything from satellite GPS positioning to how architects design curved entryways.

Honestly, it’s all about the subtraction.

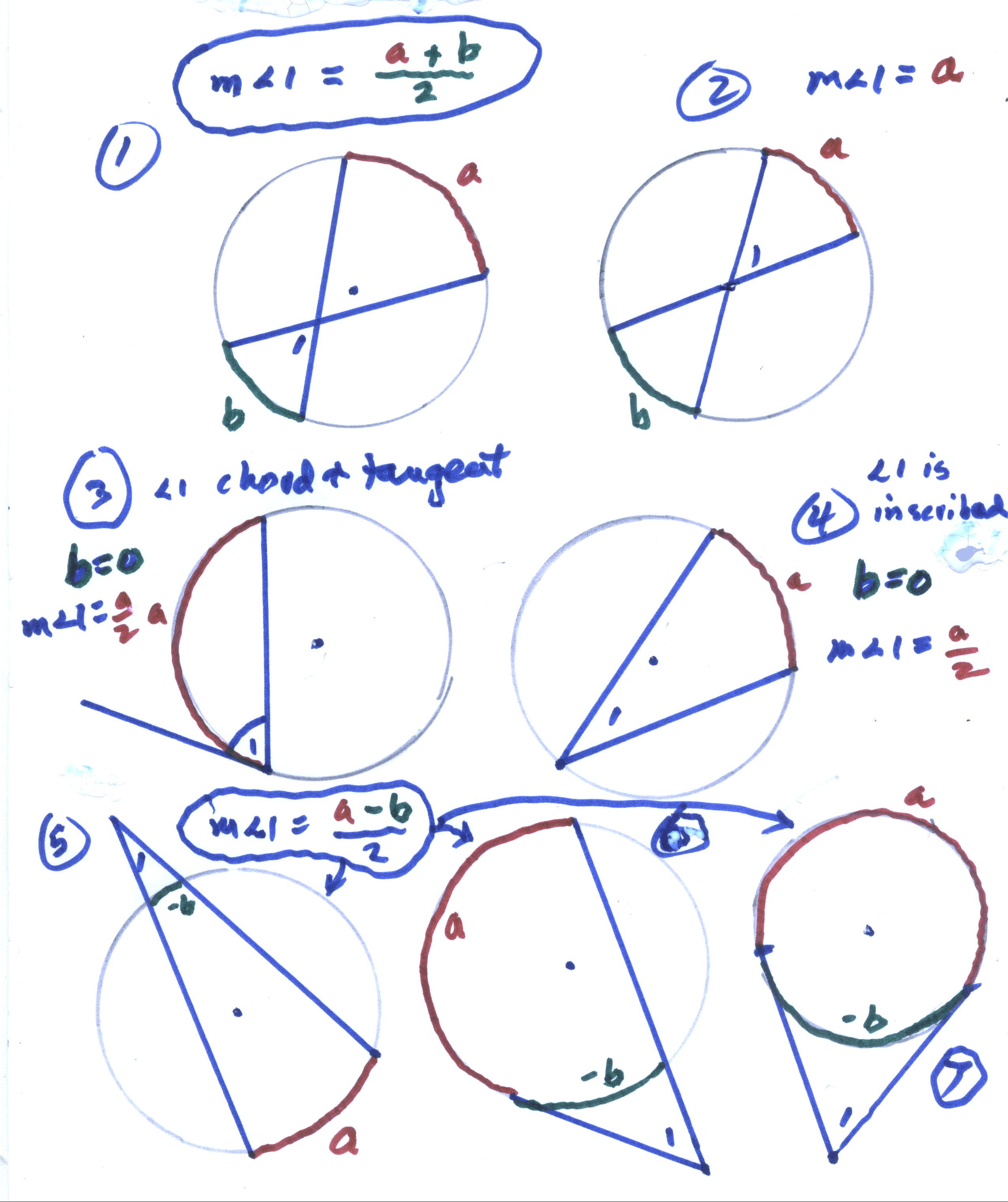

When you have an angle vertex sitting outside the circle's edge, the angle it creates is always smaller than if that vertex were shoved inside. It makes sense, right? As you pull the point further away, the "mouth" of the angle narrows. Geometry experts and hobbyists alike call this the Two-Secant Power Theorem or the Secant-Secant Angle Theorem, depending on how formal they're feeling that day. Basically, the measure of that exterior angle is exactly half the difference of the intercepted arcs.

The Core Formula Everyone Forgets

Let’s get the math out of the way so we can talk about why it matters. If you have two arcs intercepted by the angle—let's call the big one $Major Arc$ and the small one $Minor Arc$—the formula is:

$$Angle = \frac{1}{2}(Major Arc - Minor Arc)$$

🔗 Read more: Why Every Picture of Potential Energy You've Seen is Kinda Wrong

It doesn't matter if the lines are two secants, two tangents, or one of each. The physics of the circle stays the same. You take the big chunk of the circle's edge, subtract the small chunk, and cut that number in half.

Think about a lighthouse. The beam of light starts at a point (the lamp) and spreads out. If that light hits a circular island, the angle of the light that actually "hugs" the island's edges is determined by this exact relationship. If you know the arc of the island that's being illuminated, you can backtrack to find the angle of the light source. It's surprisingly practical.

Why Does This Happen?

You might wonder why we subtract. When the angle is inside the circle (an inscribed angle), we’re usually dealing with addition or just half the arc. But when you move outside, you're essentially looking at the "leftover" space.

Imagine you're standing far back from a circular stadium. Your field of vision is the angle. The stadium takes up a certain number of degrees of your 360-degree world. The further you walk away, the less of your vision the stadium occupies. This isn't just a visual trick; it's a rigid geometric property.

Real-World Case: GPS and Triangulation

We don't just do this for fun in high school. Satellite technology relies on these intersections. When a satellite sends a signal, it creates a "cone" of coverage. Where that cone intersects the Earth (which is roughly a sphere/circle in 2D cross-section), it forms arcs.

Engineers at places like NASA or Garmin use the geometry of angles outside of a circle to calculate "Dilution of Precision." If the angle between two satellites is too narrow (an exterior angle problem), your blue dot on Google Maps starts jumping all over the place. They need wide angles to get an accurate fix.

Common Mistakes That Mess People Up

People trip up on the "intercepted arcs" part.

Sometimes, you'll see a diagram where the lines don't go all the way through the circle. They might stop at the center. That’s a different ballgame. To use the "half the difference" rule, the lines must be secants or tangents that actually define two distinct arcs on the circle's circumference.

Another big one? Mixing up the order. If you subtract the major arc from the minor arc, you get a negative angle. Since we aren't dealing with vector rotations or complex phase shifts here, a negative angle usually just means you flipped your numbers. Keep it simple: Big Arc minus Small Arc.

The Tangent-Tangent Scenario

This is the "ice cream cone" look. If you have two tangents meeting at a point outside the circle, they touch the circle at exactly two points.

Here’s a cool trick: In a tangent-tangent setup, the exterior angle and the minor arc are supplementary. They add up to 180 degrees.

Why? Because the radii to the tangent points form 90-degree angles. It creates a quadrilateral where the two "corners" are 90 degrees each. Since a four-sided shape has to have 360 degrees total, the remaining two angles—the center angle (which equals the arc) and our exterior angle—must fill the remaining 180.

Solving Problems Like a Pro

If you're looking at a diagram and feel lost, try this:

- Identify the two arcs trapped between the "arms" of the angle.

- Label the far arc (the bigger one) and the near arc (the smaller one).

- Subtract.

- Divide by two.

If you have the angle but are missing an arc, just work the algebra backward. It’s usually just a basic linear equation.

💡 You might also like: Formula of lateral area of a cylinder: What most people get wrong

Actionable Insights for Geometry Mastery

- Check your lines: Ensure you are dealing with secants or tangents. If a line segment doesn't touch the circle, the rule doesn't apply.

- Visualize the "Mouth": The further the point moves away from the circle, the smaller the minor arc becomes and the smaller the angle gets. If your math shows the angle getting bigger as you move away, something is wrong.

- Use the 180-Degree Rule for Tangents: If you see an "ice cream cone" shape (two tangents), don't bother with complex subtraction if you already know the minor arc. Just subtract it from 180 to find your angle.

- Practice with Tangent-Secant Combinations: These are the "boss level" problems in most textbooks. They work exactly the same way—one arc is defined by the tangent point, the other by the secant's exit point.

Next time you see a circular archway or a satellite map, remember that the math keeping those structures and systems accurate is likely rooted in this simple subtraction trick.

Go grab a compass and a protractor. Draw a circle, pick a point outside, and measure it yourself. Seeing the math prove itself on paper is a lot more satisfying than just reading about it.