Everyone remembers the banana. You know the one—the bright yellow, slightly suggestive fruit on the cover of The Velvet Underground & Nico. It’s probably the most famous piece of rock merch in history. But if you think album covers Andy Warhol designed start and end with Lou Reed and a peelable sticker, you’re missing about 90% of the story. Warhol didn't just stumble into the music industry once he became a Pop Art god. He was obsessed with it. He was a fan, a businessman, and a bit of a social climber who realized early on that a 12-inch square of cardboard was the perfect Trojan horse for his aesthetic.

He did over fifty covers. Fifty.

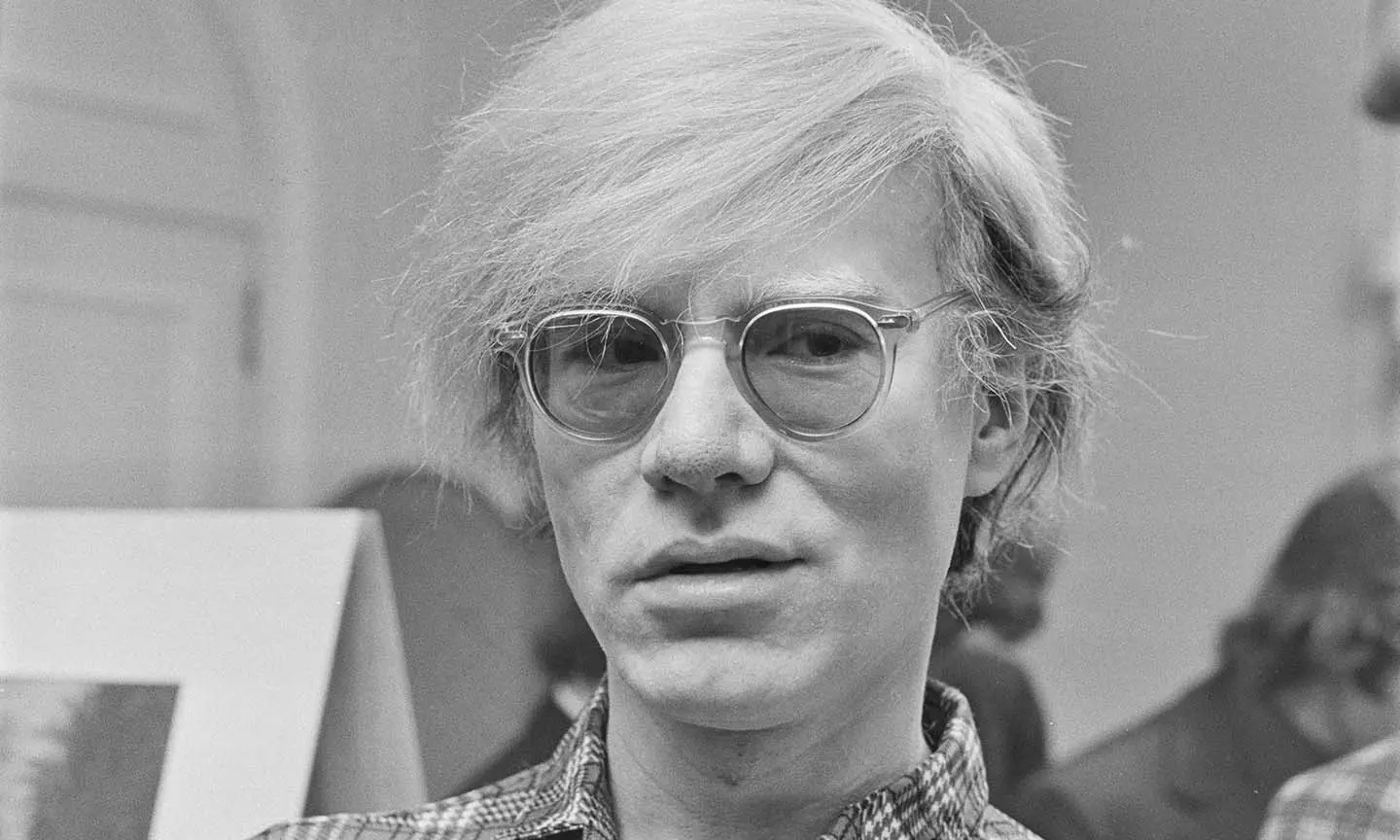

That’s a massive output for a guy who was also busy making experimental films, painting soup cans, and getting shot. From 1949 until his death in 1987, Warhol used the record sleeve as a canvas to track his own evolution. He went from a struggling freelance illustrator drawing dainty ink lines for jazz musicians to a global superstar who could make a band famous just by putting his name in the corner of their jacket.

The Pre-Pop Years: Blue Note and the Blotted Line

Before the Factory, before the silver wigs, Warhol was just Andy Warhola, a commercial artist in New York trying to pay rent. This is the era people forget. In the 1950s, he was doing a lot of work for jazz labels like Blue Note and Prestige. If you find a copy of Kenny Burrell’s Volume 2 or Thelonious Monk’s Monk, you’re looking at a Warhol.

But it doesn't look like "Warhol."

There are no neon colors or screen prints here. Instead, you get his "blotted line" technique. He’d draw in ink on wax paper and press it onto a page while it was still wet. It created this jittery, elegant, hand-drawn look that felt sophisticated and European. Honestly, it’s some of his most soulful work. He was capturing the vibe of smoky New York clubs through calligraphy. It’s wild to compare his delicate sketch for Count Basie (1955) to the aggressive, high-contrast imagery he’d produce just a decade later. He was a chameleon. He knew how to sell a sound before he knew how to sell himself.

✨ Don't miss: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

The Banana, The Zipper, and the Height of Cool

Then came 1967. The Velvet Underground.

Lou Reed’s band was basically the house band for Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable shows. When it came time to do the cover, Andy didn't just want a photo of the band. He wanted an interactive experience. The original pressings of the debut album featured a sticker that said "Peel slowly and see." If you did, you revealed a flesh-colored banana underneath. It was provocative. It was expensive to produce. MGM Records hated the cost, but they knew Warhol’s name carried weight.

Fast forward to 1971. The Rolling Stones. Sticky Fingers.

Warhol’s concept for this was even more literal. He took a photo of a man’s crotch in tight jeans (no, it wasn't Mick Jagger; it was likely Joe Dallesandro or another Factory regular) and insisted on a real metal zipper being embedded in the cardboard. It was a masterpiece of packaging, even if it famously ruined the vinyl records sitting next to it in the bins because the zipper would press into the neighboring sleeves.

These covers worked because they weren't just "art." They were objects. They were things you had to touch.

🔗 Read more: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

A Few Surprising Warhol Credits

- Aretha Franklin: Her 1986 album Aretha features a vibrant, multi-colored portrait. It was actually Warhol's final commission before he passed away.

- Billy Squier: Emotions in Motion (1982) is pure 80s Warhol. High contrast, pastel shadows, very "celebrity."

- Liza Minnelli: The Singer (1973) shows a softer side of his portraiture, focusing on the eyes and the hair.

- John Lennon: Menlove Ave. was released posthumously in 1986, featuring a haunting blue-and-yellow portrait of Lennon that Andy had done years prior.

Why Collectors Are Obsessed (and Why You Should Care)

The market for album covers Andy Warhol created has absolutely exploded. Ten years ago, you could find some of his 1950s jazz covers in thrift stores for five bucks because people didn't realize who did the art. Now? Good luck.

A mint condition Velvet Underground with the sticker intact can go for thousands. But it’s not just the big hits. Collectors are hunting for the obscure stuff—like the cover he did for a Prokofiev album in the 40s or the various "Latin" music covers he illustrated in his early years.

There’s a tension in these works. Warhol was often accused of being "soulless" or too commercial. But when you look at his record covers, you see a guy who genuinely loved the intersection of high art and low-brow consumerism. He liked that his art was being sold in Woolworths. He liked that a teenager in Ohio could own an "original" Warhol for $4.99. It was the ultimate realization of his Pop philosophy.

Misconceptions About Warhol’s Process

People think Andy sat down and painted every one of these.

He didn't.

By the 70s and 80s, the Factory was a well-oiled machine. He would take a Polaroid, his assistants would blow it up and do the silkscreening, and he would oversee the color choices. It was a collaborative process. If you’re looking for "brushstrokes," you’re looking at the wrong artist. You’re looking for the concept. The genius was in the framing—how he could take a simple photo of Debbie Harry or Diana Ross and make it look like an icon from a futuristic church.

The Transition to the Digital Age and the Legacy of the Square

Warhol died just as the CD was starting to kill the 12-inch LP. It’s a bit of a tragedy, really. Can you imagine what he would have done with a digital interface? He probably would have loved the idea of art disappearing and reappearing on a screen.

💡 You might also like: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

But the 12x12 canvas was his sweet spot.

His influence is everywhere now. Every time you see a high-contrast, "filtered" look on a modern album cover, that’s a direct descendant of the Warhol style. He taught the music industry that the artist (the visual one) was just as important as the singer. He turned the record store into a gallery.

If you're looking to start a collection, don't just go for the $500 re-issues of the Banana album. Look for the mid-career stuff. Look for the 1950s RCA Victor releases he did for classical music. They are often overlooked and represent a version of Warhol that was more "artist" than "brand."

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Collector

If you want to dive deeper into the world of album covers Andy Warhol and maybe even own a piece of this history without spending a fortune, here is how you actually do it:

- Check the Credits, Not Just the Art: Many Warhol covers don't have his signature on the front. Look for "Illustration by Andy Warhol" in tiny print on the back of 1950s jazz and classical sleeves. Brands like Blue Note, Prestige, and RCA are your best bets.

- Condition is Everything: With the Velvet Underground cover, the "unpeeled" banana is the holy grail. Even a slightly peeled one drops the value by 50%. If you find one, do not touch the sticker.

- Validate the Era: Warhol’s style changed drastically. If you find a cover that looks like a 1950s sketch but it's dated 1980, it’s a reprint or a fake. Learn to recognize the "blotted line" vs. the "silkscreen" eras.

- Visit the Warhol Museum: If you’re ever in Pittsburgh, they have an extensive archive of his commercial work. Seeing the original mock-ups for these covers is a masterclass in graphic design history.

- Look for the "Magazine" Covers: Warhol also did art for Interview magazine and various promotional flexi-discs. These are often cheaper than full LPs but carry the same historical weight.

Warhol understood that we eat with our eyes first. He made music look the way it felt—sometimes jagged and raw, sometimes smooth and expensive. Whether it's a sketch of a jazz guitarist or a photograph of a zipper, these covers remain the most accessible way to own a piece of the 20th century's most influential artist.