Ever walked into a vintage bookstore and seen a row of cloth-bound books in every color of the rainbow? If you have, you've probably met the Andrew Lang fairy books. They’re beautiful. They’re iconic. But honestly? Most of what we think we know about how they came to be is kinda wrong.

People call them "Andrew Lang’s" books, and sure, his name is the one embossed in gold on the spines. But Lang didn't actually write these stories. In fact, he barely even translated them. While he was a brilliant Scottish folklorist and a bit of a literary celebrity in late-Victorian London, the heavy lifting was done by a "coterie" of women, led by his wife, Leonora Blanche Alleyne.

Without Leonora (or Nora, as her friends called her), this 12-volume technicolor dream wouldn’t exist. She was the one digging through obscure French, German, and Italian manuscripts while Andrew was busy arguing with other academics about the origins of myths.

Why the Andrew Lang Fairy Books Almost Didn't Happen

Back in 1889, when The Blue Fairy Book first hit the shelves, the "experts" of the day were actually pretty anti-fairy tale. Weird, right?

Educators and critics thought these stories were too violent or too "unreal" for children. They wanted kids to read moralistic, educational books about real life. They thought magic would rot their brains or make them escapists. Andrew Lang thought that was total nonsense. He believed that fairy tales weren't just for kids; they were the "bridge" between literature and anthropology. He saw them as survivals of a "savage" past that every culture shared.

So, he fought back.

🔗 Read more: British TV Show in Department Store: What Most People Get Wrong

He published The Blue Fairy Book with a modest print run of 5,000 copies. It sold for six shillings. It wasn't just a hit; it was a phenomenon. It sold out almost immediately. Suddenly, everyone wanted more.

The Rainbow Sequence: More Than Just Pretty Covers

Between 1889 and 1910, the Langs released 12 volumes of fairy tales. Each one had a specific color. It was a brilliant marketing move—kinda like the Victorian version of "collect them all."

Here is the actual order they came out:

- The Blue Fairy Book (1889): The heavy hitters. "Cinderella," "Sleeping Beauty," and "Aladdin."

- The Red Fairy Book (1890): More Norse and Russian vibes. This is where you find "Jack and the Beanstalk."

- The Green Fairy Book (1892): Lang thought this might be the last one. He was wrong.

- The Yellow Fairy Book (1894): Heavy on Hans Christian Andersen and Eastern European lore.

- The Pink Fairy Book (1897): Tales from Japan and Scandinavia.

- The Grey Fairy Book (1900): A bit more obscure, with Greek and Lithuanian stories.

- The Violet Fairy Book (1901): Romanian and Japanese legends.

- The Crimson Fairy Book (1903): This one gets exotic—Hungarian, Russian, and even some African tales.

- The Brown Fairy Book (1904): Native American and Australian Indigenous stories (though, admittedly, through a very Victorian lens).

- The Orange Fairy Book (1906): Tales from Jutland and Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe).

- The Olive Fairy Book (1907): Mostly Punjabi and Armenian stories.

- The Lilac Fairy Book (1910): The final installment.

By the time they reached the Lilac volume, Andrew finally came clean in the preface. He admitted that the series had been "almost wholly the work of Mrs. Lang." She translated, adapted, and polished the narratives to make them readable for a British audience.

The Controversy: To Bowdlerize or Not?

The Langs weren't just copying and pasting. They were "bowdlerizing."

💡 You might also like: Break It Off PinkPantheress: How a 90-Second Garage Flip Changed Everything

That’s a fancy way of saying they scrubbed the stories. If a story was too sexual or too gruesome for a Victorian nursery, Nora would snip those parts out. J.R.R. Tolkien, the Lord of the Rings guy, actually hated this. In his famous essay "On Fairy-Stories," he complained that the Langs had "relegated" fairy tales to the nursery, treating them like "furniture" for children rather than serious art.

Tolkien also pointed out that some of the stories weren't even fairy tales. For example, "The Heart of a Monkey" in the series doesn't have any real magic; the monkey just tricks a shark by lying. To a purist like Tolkien, that's just a fable, not a "fairy" story.

But for most of us? These books are the reason we know these stories at all. Before the Andrew Lang fairy books, many of these tales hadn't ever been printed in English.

Henry Justice Ford: The Man Behind the Magic

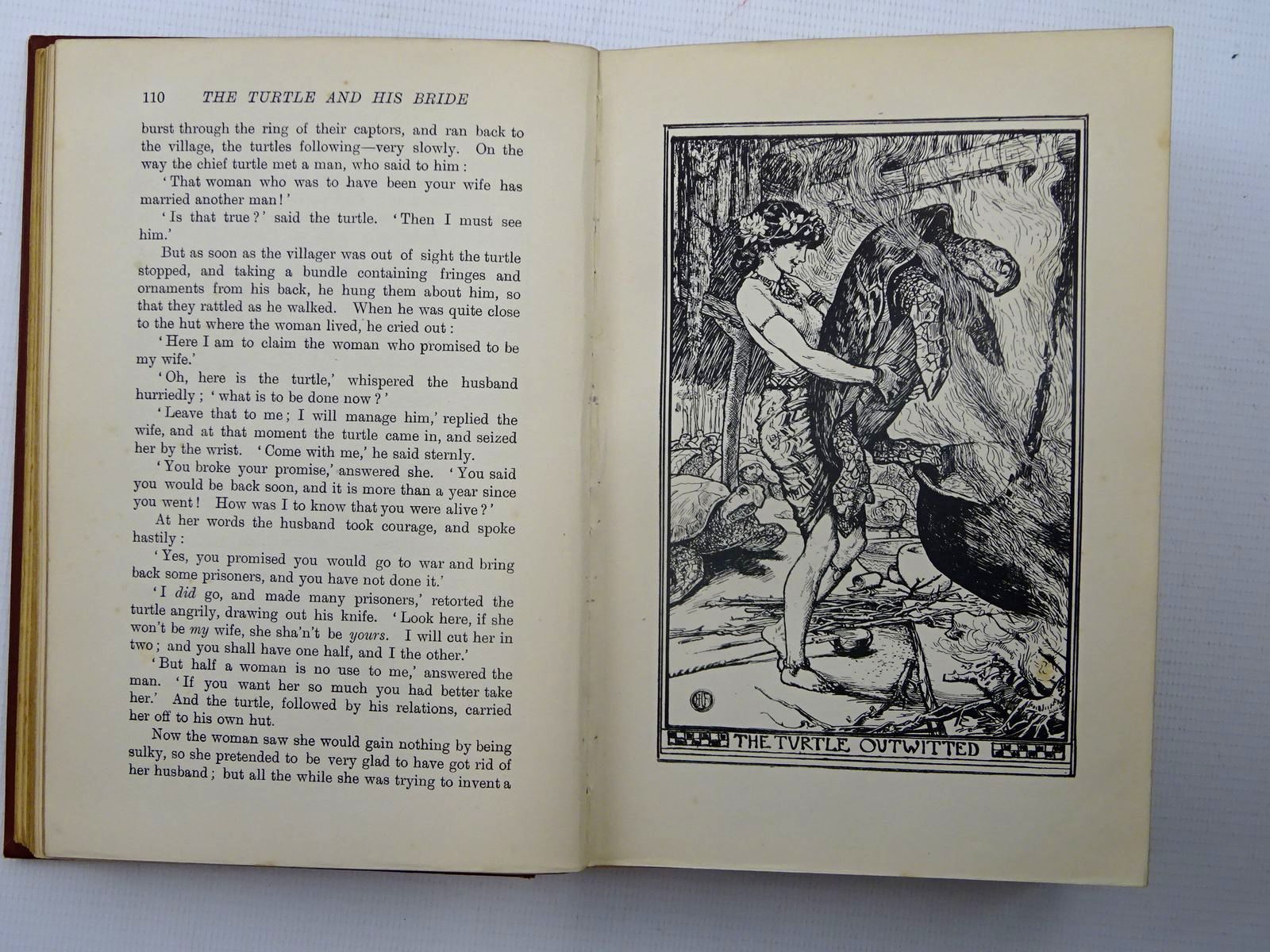

You can't talk about these books without mentioning the art. Henry Justice Ford (H.J. Ford) was the primary illustrator. His intricate, black-and-white ink drawings are what give the books their soul.

He had this way of drawing dragons that looked terrifying but also strangely elegant. His princesses weren't just "pretty"; they looked like they were part of a Pre-Raphaelite painting. In the original editions, his work wasn't just decoration—it was part of the storytelling. Modern reprints often struggle to capture the fine detail of his lines, which is why finding an original or a high-quality facsimile is such a big deal for collectors.

📖 Related: Bob Hearts Abishola Season 4 Explained: The Move That Changed Everything

How to Get Your Hands on Them Today

If you’re looking to start a collection, you have a few options.

- Dover Publications: These are the "working class" editions. They’re paperbacks, usually around $15, and they keep all the original H.J. Ford illustrations. They aren't fancy, but they’re great for actually reading.

- The Folio Society: If you want the "I have a library and smoke a pipe" look, these are the ones. They are massive, buckram-bound, and expensive. Each volume uses a different modern illustrator, which is cool, but some people miss the old Ford drawings.

- Antique Originals: Finding a first-edition Blue Fairy Book in good condition will cost you hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars. The later colors like Olive or Lilac are often even harder to find because they had smaller print runs.

Basically, if you see a "Coloured Fairy Book" in a thrift store for five bucks, buy it. Don't think. Just buy.

What to Do Next

If you want to dive into the world of the Andrew Lang fairy books, don't just start at the beginning. Most people find the Blue and Red books a bit too familiar because they contain the Disney-fied classics.

Instead, try these three things:

- Read the prefaces: Andrew Lang was a snarky, brilliant writer. His introductions are full of shots fired at his academic rivals and are surprisingly funny.

- Look for the Brown or Olive books: These contain stories from cultures you probably didn't grow up with. The perspectives are fascinatingly different from the standard European "once upon a time."

- Check out the digital versions: Since these are in the public domain, you can find the full text and all the original illustrations for free on Project Gutenberg or the Internet Archive. It’s a great way to see if you actually like the prose before dropping money on a physical set.

Ultimately, these books aren't just relics. They represent a moment in history when people decided that magic was worth saving. And thanks to Nora Lang's tireless translating and Andrew's stubborn defense of "unreality," we still have them on our shelves today.