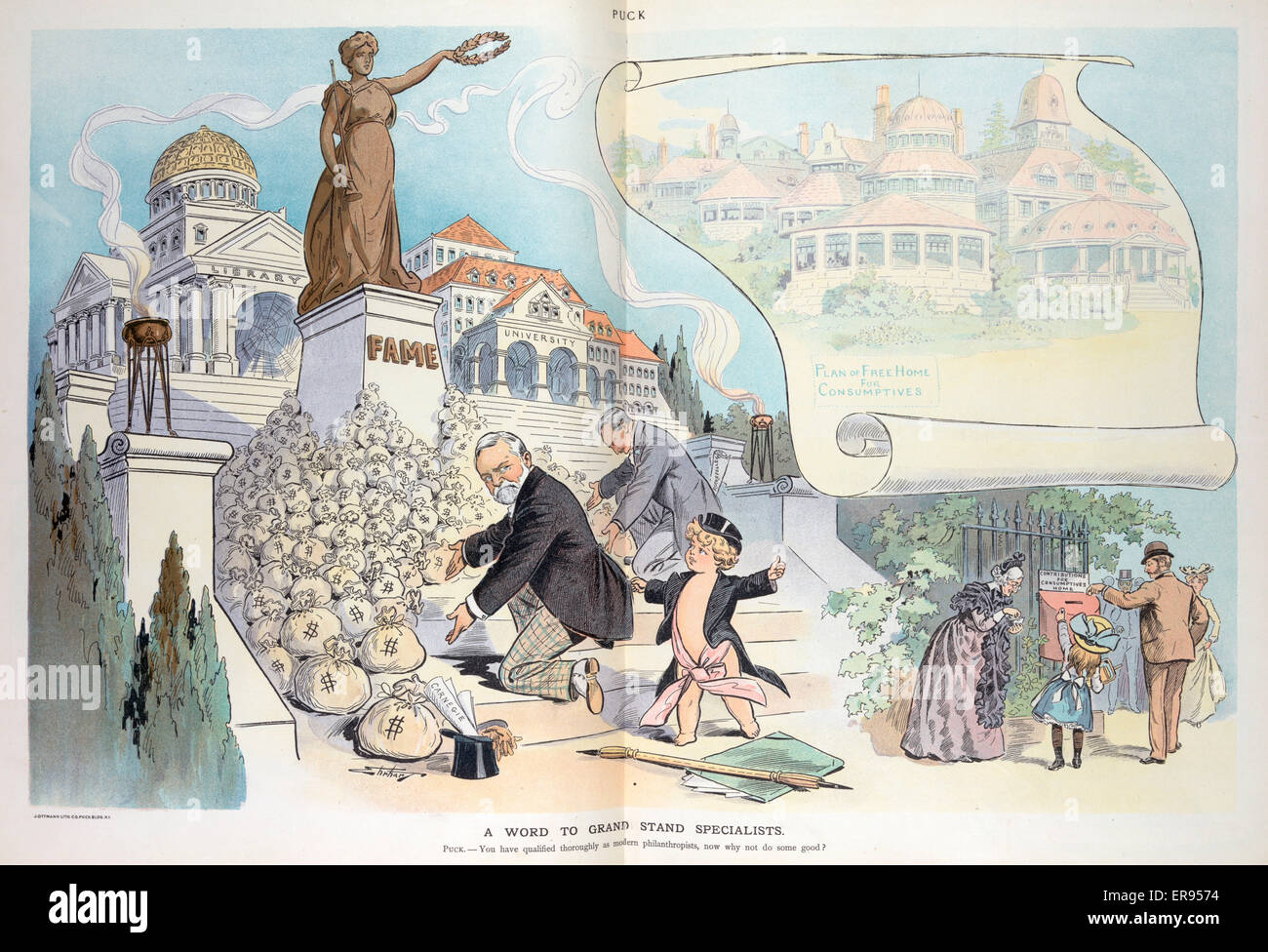

History has a funny way of smoothing out the rough edges of famous people. You probably know Andrew Carnegie as the "Library Guy"—the benevolent Scottish immigrant who gave away 90% of his fortune. But if you were reading a newspaper in the 1890s, you’d see a very different version of him.

Back then, the Andrew Carnegie political cartoon was a staple of American media. These drawings didn't just poke fun at his accent or his short stature; they were brutal, biting critiques of a man who seemed to have two different souls. One soul built concert halls, while the other slashed the wages of the men who actually made the steel.

The "Double Face" of the Gilded Age

There is one specific image that honestly sums up the whole era. It’s a cartoon published in the Saturday Globe in 1892, right after the Homestead Strike. It shows Carnegie with a literal split personality. On one side, he’s a doting philanthropist handing out bags of money for libraries. On the other side, he’s a ruthless "robber baron" using a club to beat down his workers.

👉 See also: Jeff Wald Net Worth: What Most People Get Wrong

The irony wasn't lost on the public.

Carnegie had spent years writing essays like "The Gospel of Wealth," where he argued that the rich had a moral duty to give back. He even wrote articles supporting the right of workers to strike. But when the rubber hit the road at his own steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, things got ugly.

While Carnegie was tucked away in a castle in Scotland, his partner Henry Clay Frick brought in the Pinkertons—basically a private army—to crush a strike. People died. Blood was literally on the riverbanks.

The cartoonists of the time went wild. They started drawing Carnegie as a hypocrite. They’d show him offering a "library" to a starving family that just wanted enough money to buy bread. It’s a classic trope: "I won't give you a living wage, but here’s a book on how to improve yourself."

Why the "MacMillion" Tag Stuck

The British magazine Punch had a field day with him too. In 1901, they published a famous piece titled "The MacMillion." In this one, Carnegie is wearing a kilt—playing up his Scottish roots—and he’s literally showering Scotland with gold coins. He’s standing on a poster for "Free University Education." At a glance, it looks like a tribute. But if you look at the faces of the people in these cartoons, there’s often a sense of "too little, too late" or a critique of how he obtained that money in the first place.

You see, Carnegie didn't just give money; he gave it with strings attached. He’d build the library building, but the town had to agree to pay for the books and the upkeep forever.

Some towns actually refused the "gift."

One glassworker at the time famously said he’d rather enter a building built with Judas's silver than a Carnegie library. That's the kind of raw anger these political cartoons were tapping into. They weren't just funny drawings; they were the "Twitter threads" of 1892, fueling a massive public debate about whether someone can be a good person if their business practices are predatory.

The Hydra and the Trusts

Then there’s the "A Trustworthy Beast" cartoon from HarpWeek. This one is a bit more complex but super telling of the business climate.

It depicts a calm, smiling Carnegie talking to an incredibly stressed-out Uncle Sam. Behind Carnegie is a terrifying, multi-headed monster. Each head represents a different industry Carnegie had his hands in:

📖 Related: Iraqi Dinar News Today: What Most People Get Wrong

- Steel (the big one)

- Lumber

- Oil

- Sugar

- Salt

Carnegie is telling Uncle Sam that "trusts" (monopolies) are totally harmless. Meanwhile, the monster is literally snarling in the background. It perfectly captured the fear that these industrial giants were becoming more powerful than the government itself.

The Peace Pipe and the Kaiser

Later in his life, the Andrew Carnegie political cartoon shifted focus. As he got older, Carnegie became obsessed with world peace. He even built the "Peace Palace" in the Hague.

Cartoonists started drawing him as a bit of a naive dreamer. There’s a famous one where Carnegie, looking like a tiny leprechaun, is offering a "peace pipe" to the German Kaiser and other world leaders. The artists were mocking him. To them, the idea that a man who built his fortune on the materials of war (steel for battleships and armor) could suddenly buy world peace was hilarious—and a bit sad.

What This Means for Us Today

Honestly, looking at an Andrew Carnegie political cartoon from 130 years ago feels weirdly modern. We do the same thing today with tech billionaires. We praise their foundations while criticizing their tax breaks or how they treat their warehouse staff.

The cartoons remind us that history isn't black and white. Carnegie wasn't just a hero, and he wasn't just a villain. He was both, and the media of his day was determined to make sure nobody forgot the "other" side of the checkbook.

✨ Don't miss: Another Word for Foreman: Why the Right Title Actually Changes Your Payroll

If you're looking into this for a school project or just because you’re a history nerd, here is the best way to analyze these:

- Look at the hands: In almost every Carnegie cartoon, what he is doing with his hands (giving vs. taking) is the key to the message.

- Check the background: The "clutter" in the back usually represents the workers or the "trusts" he's trying to hide.

- Read the captions: They often used Carnegie's own quotes against him to highlight his hypocrisy.

To see these for yourself, the Library of Congress and the HarpWeek archives are the gold standard. They have high-res scans that let you see the tiny details, like the labels on the money bags or the expressions on the faces of the Pinkerton guards.

Start by searching for the "Promise and Performance" cartoon from 1892. It's the most brutal one out there, showing Carnegie sitting on a pile of money while telling workers they're "fools" for believing his promises. It's a masterclass in Gilded Age satire.