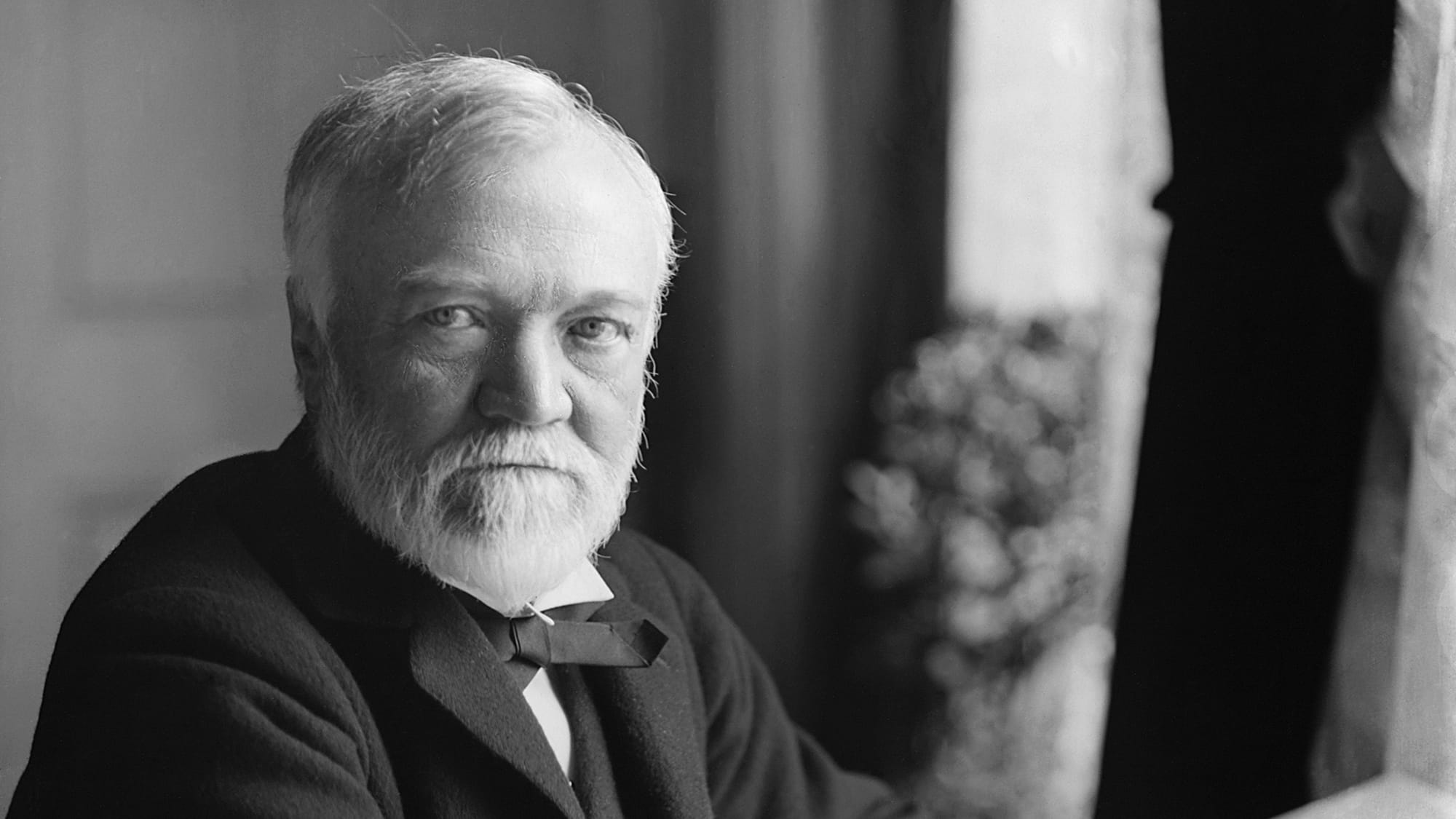

Andrew Carnegie was kind of a walking contradiction. Honestly, you've probably heard the name associated with two very different things: massive libraries and the brutal Homestead Strike of 1892. One side of the guy spent his sunset years giving away $350 million—basically 90% of his fortune—while the other side oversaw a steel empire that worked men to the bone for pennies. In 1889, he sat down and wrote an essay originally titled just "Wealth," which we now call Andrew Carnegie the Gospel of Wealth. It wasn't just a guide on how to be a nice rich guy. It was a radical, somewhat elitist, and surprisingly aggressive manifesto on why leaving money to your kids is a terrible idea and why the state should tax the hell out of dead millionaires.

The "Gospel" basically argues that the rich aren't just lucky; they’re "trustees" for the public. Carnegie thought most people couldn't handle money properly. He believed that if you just handed out cash to the poor, they’d spend it on "the slothful, the drunken, the unworthy." Instead, he wanted to build "ladders" like libraries and universities so the "worthy" could climb up themselves. It’s a harsh worldview that still dictates how billionaires like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett operate today.

Why Andrew Carnegie the Gospel of Wealth Still Matters

We live in a world where the wealth gap is wider than it was in the Gilded Age. Carnegie saw this coming. He actually argued that the "concentration of business" in the hands of a few was actually good for the race. Why? Because he thought a few smart, capable men could manage that money better than the government or the "masses" ever could. It sounds arrogant because it was. But he also felt that this power came with a heavy, soul-crushing responsibility.

He famously said, "The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced."

Carnegie wasn't kidding. He hated the idea of hereditary wealth. To him, the British aristocracy was a joke—a bunch of "spoiled" kids who did nothing for society. He pushed for heavy inheritance taxes. He wanted to make it so that if a rich man tried to hoard his gold until the grave, the state would step in and take a massive cut. He believed the wealthy should be "mere agents" for their "poorer brethren," using their "superior wisdom" to spend the money for the general good while they were still alive.

✨ Don't miss: Online Associate's Degree in Business: What Most People Get Wrong

The Problem with "Indiscriminate Charity"

One of the most controversial takes in the essay is Carnegie's loathing of traditional charity. He estimated that out of every $1,000 spent on charity in his day, $950 was "unwisely spent." He thought giving a beggar a nickel was a sin because it just encouraged them to stay a beggar.

If you want to understand the Andrew Carnegie the Gospel of Wealth philosophy, you have to look at the libraries. He built 2,509 of them. But here’s the kicker: he wouldn’t pay for the books or the staff. He only paid for the building. The local community had to prove they wanted the library by agreeing to tax themselves to maintain it. He provided the "ladder," but you had to do the climbing.

The Dark Side of the Gospel: The Homestead Strike

You can't talk about Carnegie's "Gospel" without talking about where the money came from. It came from steel. Specifically, it came from the sweat of workers in places like Homestead, Pennsylvania. While Carnegie was writing about how the rich and poor should be bound in "harmonious relationship," his manager, Henry Clay Frick, was busy crushing a union.

In 1892, while Carnegie was vacationing in a remote Scottish castle, Frick locked out workers and hired 300 Pinkerton detectives to storm the plant. A literal war broke out. People died. Carnegie stayed in Scotland, sending letters of support to Frick, only to express "regret" years later. This is the central tension of his legacy. He slashed wages to maximize the "surplus wealth" he felt so "morally bound" to give away later. It’s a weird, circular logic: I have to be a "robber baron" today so I can be a "saint" tomorrow.

🔗 Read more: Wegmans Meat Seafood Theft: Why Ribeyes and Lobster Are Disappearing

A Legacy of Institutional Philanthropy

Despite the blood on the floor of the steel mills, the impact of his giving is staggering. He didn't just give to libraries. He founded:

- The Carnegie Corporation of New York (which funded the discovery of insulin and Sesame Street).

- Carnegie Mellon University.

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- The Carnegie Hero Fund.

He wasn't interested in temporary fixes. He wanted "permanent good." This is why he focused on institutions. He believed that a library or a park would benefit a community for a hundred years, whereas a soup kitchen would only help for an afternoon. It’s a "teach a man to fish" philosophy taken to a massive, industrial scale.

Common Misconceptions About Carnegie’s Philosophy

People often think Carnegie was a socialist because he supported high taxes on the rich. He wasn't. He was a hardcore capitalist who believed competition was the "law of the universe." He just thought the "winners" of capitalism shouldn't be allowed to keep the trophies for themselves.

Another big mistake is thinking he was religious. Though he called it a "Gospel," Carnegie was more of a Social Darwinist. He used religious language to sell a secular, civic duty. He didn't think you'd go to hell for being rich; he thought you’d be a social failure. He wanted to replace the "aristocracy of birth" with an "aristocracy of talent and service."

💡 You might also like: Modern Office Furniture Design: What Most People Get Wrong About Productivity

Actionable Insights from the Gospel of Wealth

If we strip away the 19th-century language and the ego, what can we actually learn from Andrew Carnegie the Gospel of Wealth? His ideas provide a framework for anyone thinking about their legacy, whether they have millions or just a few extra bucks.

- Be a "Trustee," Not a Hoarder: View your resources (time, money, skills) as something to be managed for the benefit of others, not just for personal luxury.

- Focus on "Ladders," Not "Handouts": When helping, look for ways to empower people to help themselves. Support education, mentorship, and tools that provide long-term growth.

- Give While You’re Alive: Carnegie’s biggest point was that you should be the one directing your wealth. If you wait until you’re gone, someone else will probably mess it up or use it for something you’d hate.

- Expect Excellence: Carnegie didn't just throw money at problems. He demanded that the communities he helped show skin in the game. Real change usually requires a partnership, not just a donation.

Carnegie’s life was messy. He was a man who preached peace but profited from armor plate. He spoke of the "brotherhood" of the poor while his managers broke their strikes. But the Andrew Carnegie the Gospel of Wealth remains the most influential document in the history of philanthropy because it forced the world to ask: What do the winners of the economic game owe to the people who helped them get there?

If you're interested in how this philosophy evolved into the modern "Giving Pledge" signed by billionaires today, you should look into the Carnegie Corporation’s current projects. They continue to fund everything from nuclear non-proliferation to education reform. You can also visit one of the many "Carnegie" libraries still standing to see the physical manifestation of a man who believed that books were the ultimate tool for human progress.