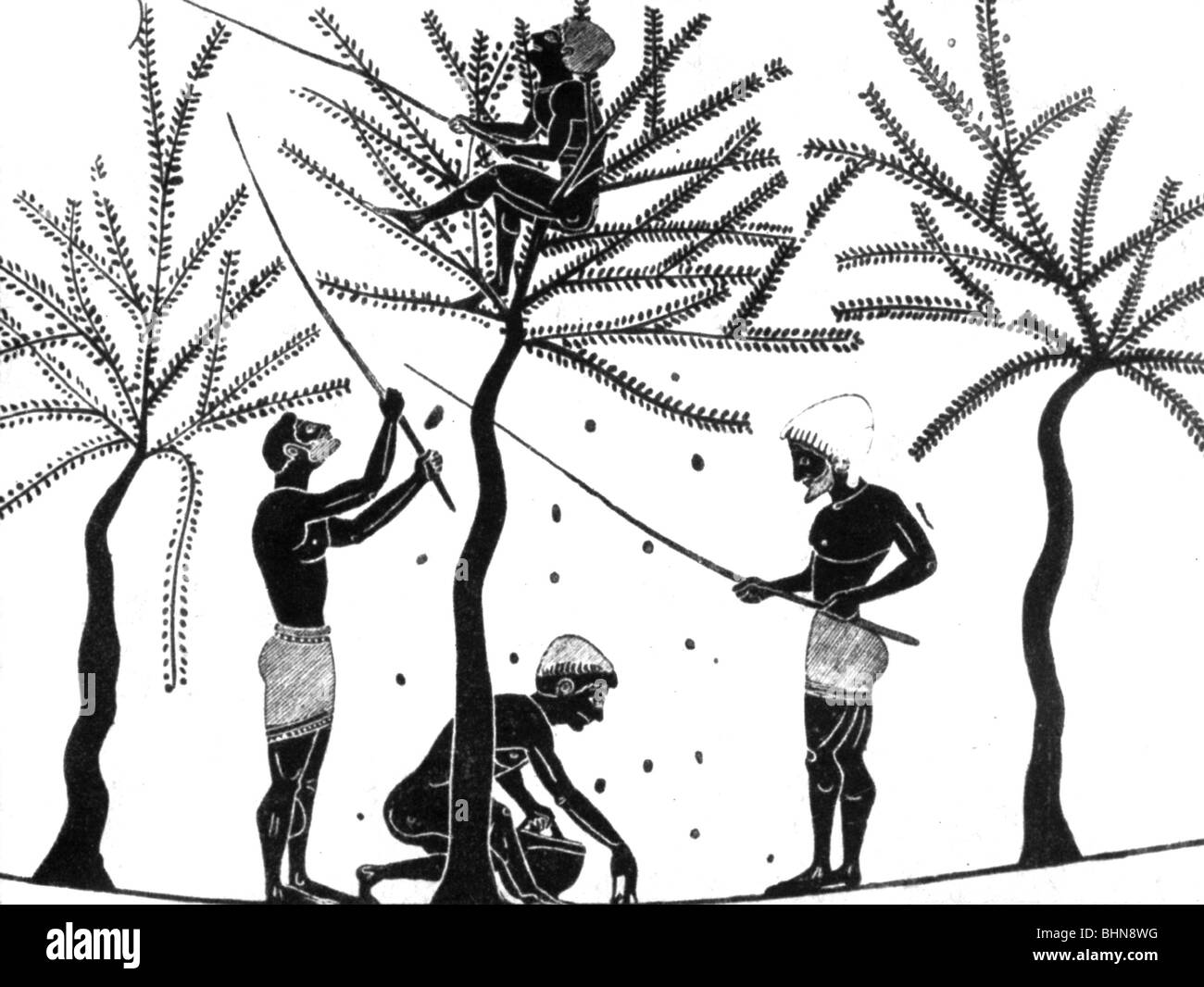

When you scroll through ancient Greece agriculture pictures on a museum website or a history blog, you’re usually looking at one of two things: a black-figure vase showing a man knocking olives off a tree with a stick, or a romanticized 19th-century painting of a lush hillside.

The reality was grittier. Honestly, it was a constant struggle against a landscape that didn't really want to cooperate. About 80% of the population were farmers. That’s a massive chunk of people just trying to squeeze enough calories out of thin, rocky soil to survive the winter. They weren't just "farmers" in the modern sense; they were survivalists.

Why Ancient Greece Agriculture Pictures Only Tell Half the Story

If you look at the famous "Olive Picker" vase in the British Museum, it looks peaceful. It’s almost serene. But if you've ever actually tried to harvest olives by hand, you know it’s back-breaking, sticky, and incredibly tedious work. The images we have from the Archaic and Classical periods are often idealized or highly stylized. They were created for the elite, not for the guys actually doing the digging.

Greece is mostly mountains. In fact, only about 20% to 30% of the land was even remotely arable. This meant that every square inch of flat land was precious. Farmers practiced something called "dry farming," relying on rain rather than the massive irrigation systems you’d see in Egypt or Mesopotamia. If the rain didn't come, people starved. It was that simple.

Ancient Greek farmers were masters of the "Mediterranean Triad": grain, grapes, and olives. Grain (mostly barley because it’s tougher than wheat) provided the calories. Grapes provided the wine, which was safer to drink than some water sources and a huge trade commodity. Olives provided the fat, the light (lamp oil), and the soap.

The Hidden Labor in the Soil

When you see ancient Greece agriculture pictures depicting the plow, you’re seeing a tool called the aratron. It was a light, scratch-plow. It didn't turn the soil over like a heavy medieval plow; it just scratched the surface. Why? Because if you turned the soil too deep in a Mediterranean climate, you’d lose all the moisture to the sun.

🔗 Read more: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

The labor was intensely seasonal.

Autumn was the most stressful. You had to plow and sow the grain right after the first rains softened the earth. If you missed that window, you were done for. Then came the pruning of the vines in winter, the harvest of grain in early summer, and the olive press in late autumn. It was a never-ending cycle of high-stakes physical exertion.

Historian Victor Davis Hanson, who actually ran a family farm before becoming a scholar, argues in The Other Greeks that this grueling lifestyle actually created the foundation for Greek city-state democracy. These small-scale, independent farmers—the georgoi—were the ones who fought in the phalanx. They had "skin in the game." They weren't just peasants; they were citizen-soldiers whose politics were shaped by the dirt under their fingernails.

The Evolution of Farming Tools and Techniques

We often think of ancient tech as primitive, but they were remarkably efficient with what they had. You’ll see images of the "ox-drawn plow," but what the pictures don't show is the sheer cost of keeping an ox. Most small-scale farmers couldn't afford one. They used mattocks and hoes. They were the engine.

- The Mattock (Dikella): A heavy, two-pronged tool used to break up the hard crust of the earth.

- The Sickle (Drepanon): Used for reaping grain. You’d grab a handful of stalks and slice.

- The Winnowing Fan: After threshing the grain (often by having oxen or mules walk over it on a stone floor), you’d toss it into the air. The wind would blow away the light chaff, and the heavy grain would fall back down.

Terracing was another massive feat. If you look at the hillsides of Delos or the rugged terrain of Attica today, you can still see the remains of ancient stone walls. They built these to catch the soil and prevent erosion. It turned vertical, useless rock into horizontal, productive strips. This wasn't a one-time job; it required constant maintenance. One heavy rainstorm could wash away a decade of work if a wall failed.

Bees, Pigs, and the Small Stuff

Not every farm was a sprawling estate. Most were small, diversified plots. You’d have a few rows of vines, some olive trees, maybe a vegetable garden with onions, garlic, and legumes (beans were huge for soil nitrogen).

💡 You might also like: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

Animal husbandry was a luxury. Most families had a few goats or sheep for wool and milk (cheese was a staple, meat was rare). Pigs were the "trash compactors" of the ancient world. They ate the scraps and provided high-quality fat. Honey was the only sweetener, so beekeeping was a specialized but vital part of the landscape.

What the Archaeological Record Reveals

Beyond the pottery, we have the charred remains of seeds and pollen analysis. This "bio-archaeology" tells us things the ancient Greece agriculture pictures can't. For instance, we know that as populations grew in places like Athens, the local farms couldn't keep up.

Athens became obsessed with the "Grain Way"—the shipping route from the Black Sea. This is a huge reason why their navy was so important. It wasn't just for war; it was for groceries. If the grain ships from what is now Ukraine and Russia didn't arrive, the city-state would collapse. This geopolitical reality is often missed when we just look at a picture of a man with a hoe.

There’s also the issue of soil exhaustion. The Greeks knew about fallowing—leaving a field empty for a year to recover—but when you’re hungry, it’s hard to leave a field empty. They used manure, of course, but it was never enough. They were always teetering on the edge of an ecological breaking point.

Misconceptions About Slavery and Farming

There’s a common idea that all Greek farming was done by slaves while the citizens sat around talking philosophy. That’s a bit of an oversimplification. While wealthy estates certainly used enslaved labor, the "middling" farmer—the guy with 10 or 15 acres—worked right alongside his slaves if he had them. It was a shared misery of heat and dust. In many cases, the "farm" was a family affair where everyone, regardless of status, was involved in the harvest.

📖 Related: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

If you want to truly understand the agricultural world of the Greeks, don't just look at the art. Use these steps to get a more accurate picture:

- Study the "Geoponika": This is a much later Byzantine compilation, but it contains a massive amount of ancient agricultural lore, from how to treat sick oxen to the best time to plant cucumbers.

- Examine the Hesiod’s "Works and Days": Read this poem. It’s essentially a farmer’s almanac from the 8th century BCE. It’s grumpy, practical, and gives you the real "vibe" of ancient farming life—lots of complaining about the weather and lazy neighbors.

- Look at Topography, Not Just Art: Use Google Earth to look at the terrain around ancient sites like Corinth or Sparta. Seeing the mountains helps you realize why the Greeks were so obsessed with finding every scrap of flat land.

- Visit the Museum of Ancient Greek Technology: If you’re ever in Athens or Katakolo, check out the Kotsanas Museum. They have reconstructed models of the oil presses and winches that the Greeks used to process their harvests.

The next time you see ancient Greece agriculture pictures, look past the artistic style. Look for the callouses. Look for the sweat. The Parthenon was built on the surplus of barley and olives, and the men who voted in the assembly were usually the same ones who had spent the morning worrying about the lack of rain or the health of their vines. That connection to the land is what actually fueled the "Golden Age."

Without the humble, dirty, repetitive work of the georgos, there would be no Socrates, no Sophocles, and no democracy. It all started in the dirt.

Next Steps:

To deepen your understanding, research the "Black Sea Grain Trade" to see how international commerce supported Greek urban centers, or look into "Paleobotanical studies in the Peloponnese" for the hard data on what crops were actually grown in different centuries.