Look at a textbook from the 19th century and you’ll see something striking. Those hand-drawn, ink-washed anatomy pictures of the human body look almost identical to what a medical student stares at today on an iPad. It’s weird, right? We have robotic surgery and CRISPR gene editing, yet we still rely on two-dimensional drawings to understand the most complex machine in the known universe.

Most people think a photo is better than a drawing. It’s not.

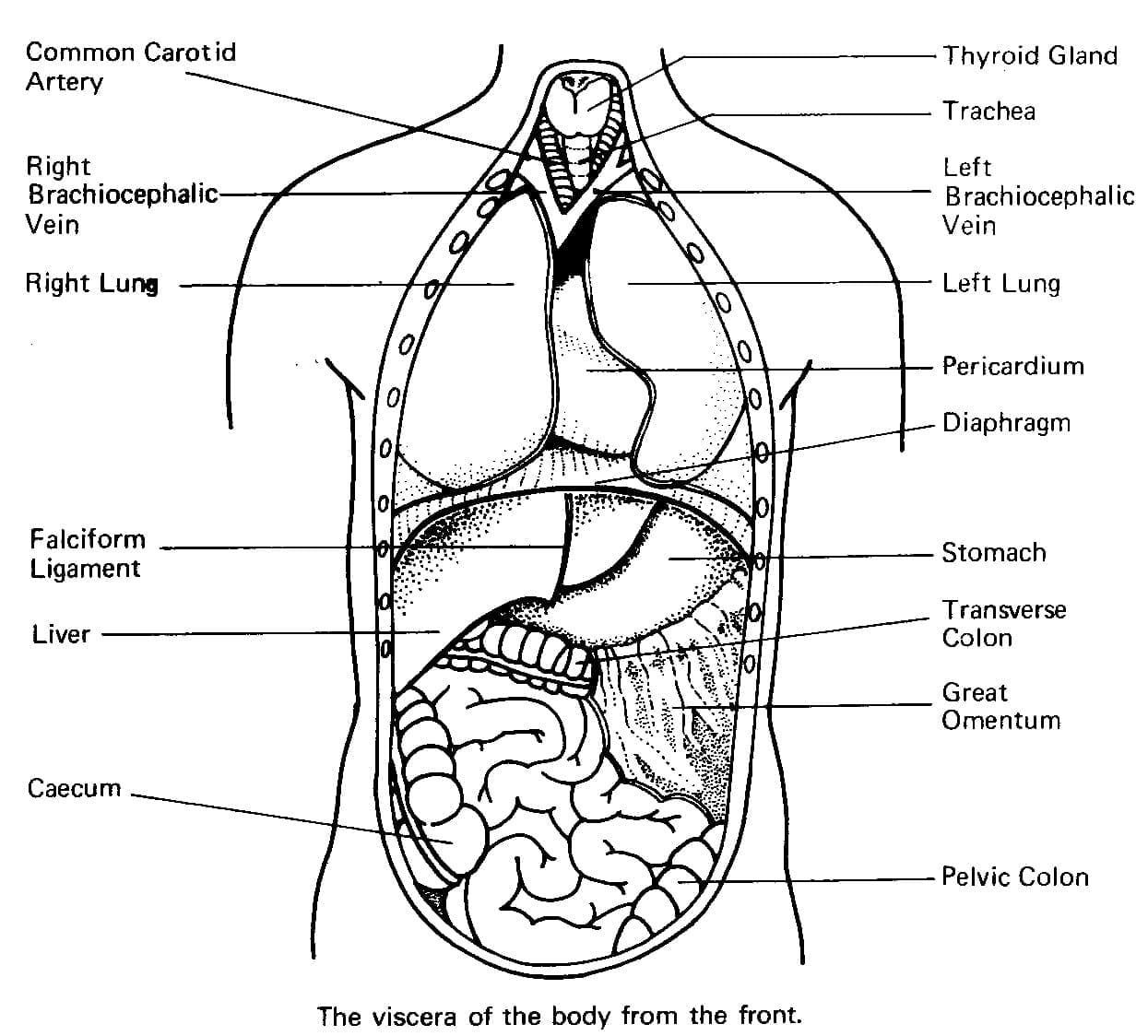

If you’ve ever looked at a real cadaver or a high-resolution surgical photo, you know the truth: the inside of a person is a messy, monochromatic blob of beige and red. It’s "wet-ware." Real tissue doesn’t come color-coded. That’s why medical illustrators are the unsung heroes of healthcare. They take that biological chaos and turn it into a map. Without these curated visuals, most of us wouldn’t know the difference between a nerve and a tendon. Honestly, even some first-year med students struggle with it during their first week in the lab.

The Lie of the "Standard" Human Body

We have this idea that there is a "perfect" anatomy. You see it in every poster in every doctor’s office. The muscles are perfectly symmetrical. The veins are always where they "should" be.

Real life is messier.

Anatomic variation is the rule, not the exception. Dr. Jean-Baptiste Winslow, a pioneer in the 1700s, was one of the first to really harp on this. Some people are born with an extra rib. Others have their organs flipped—a condition called situs inversus. If you only ever look at stylized anatomy pictures of the human body, you’re looking at a "median" version of humanity that doesn't actually exist in any single person.

Why the Gray’s Anatomy Style Still Dominates

Henry Gray and illustrator Henry Vandyke Carter changed the world in 1858. Their book, Anatomy: Descriptive and Surgical, succeeded because of the pictures. They weren't just drawings; they were functional diagrams. Before them, many medical texts were dense walls of Latin with a few clunky sketches in the back. Carter placed the labels on the structures.

It sounds simple. It was revolutionary.

Today, companies like Netter (named after the legendary Frank H. Netter, MD) carry that torch. Netter was known as "Medicine's Michelangelo." Why? Because he knew how to exaggerate the right things. He would make a nerve slightly brighter or a fascia layer slightly more translucent. This isn't "fake" news; it's pedagogical clarity. He was making the invisible visible.

🔗 Read more: In the Veins of the Drowning: The Dark Reality of Saltwater vs Freshwater

What Most People Get Wrong About Looking at Themselves

When you Google "anatomy pictures of the human body," you probably want to find out why your lower back hurts or what that weird lump on your wrist is. But 2D images can be deceptive.

Take the "Core."

People think the core is just the six-pack (the rectus abdominis). If you look at a deep-layer anatomical plate, you’ll see the transversus abdominis and the multifidus. These are tiny, thin muscles that act like a corset. You can't see them in a mirror. You can barely see them in most "fitness" anatomy sketches. But they are the reason your spine doesn't collapse when you pick up a grocery bag.

The Fascia Revolution

For a long time, anatomy pictures basically ignored fascia. They treated it like "packing peanuts" for the body. You’d see the muscles clearly defined, but the white, spider-webby stuff covering them was stripped away in the drawings.

We now know fascia is a sensory organ. It’s loaded with nerve endings. Modern anatomical artists like those contributing to the Journal of Biomechanics are now starting to include these connective tissues in their renderings. It’s changing how we treat chronic pain. If you're looking at an old-school chart, you're missing half the story of how you actually move.

3D Models vs. The Classic Drawing

There’s a lot of hype around VR anatomy. "Put on these goggles and walk through a heart!"

It’s cool. It’s also often distracting.

Research from the Anatomical Sciences Education journal has shown that while students love the "wow" factor of 3D, they often retain more from 2D illustrations. Why? Because a 2D drawing forces a perspective. It highlights the "teaching point." In a 3D model, the student gets lost in the rotation. They spend more time playing with the interface than memorizing the path of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

💡 You might also like: Whooping Cough Symptoms: Why It’s Way More Than Just a Bad Cold

The Ethics of the Image

We have to talk about where these images come from. Historically, it’s dark. Many of the most famous anatomy pictures of the human body from centuries past were based on the bodies of executed prisoners or victims of "resurrection men" (grave robbers).

Even the Pernkopf Epitome, once considered the pinnacle of anatomical art, is now largely banned or restricted because it was created using the bodies of victims of the Nazi regime.

Today, we have the Visible Human Project. In the 1990s, the National Library of Medicine took a cadaver—Joseph Paul Jernigan, who donated his body—and sliced it into 1,871 thin sections. They photographed every slice. It’s the ultimate, ethically sourced data set for every modern digital anatomy tool you use. It’s the "Gold Standard."

How to Actually Use Anatomy Pictures for Better Health

If you are using these images to understand your own body, stop looking at the superficial "skin off" muscle man. He's not helpful for most things.

Instead, look for Cross-Sections.

A cross-section (imagine slicing a person like a loaf of bread) shows you the relationship between organs. It shows you how close the kidneys are to the back muscles. It shows you how the intestines are actually coiled. This is how doctors read CT scans and MRIs. If you can understand a cross-sectional anatomy picture, you can understand your own medical imaging.

The Problem with Color

Blue is deoxygenated blood, red is oxygenated. We all learned this in fifth grade.

Except, in your body, your veins aren't blue. They’re a dull, dark red or brownish-purple. The blue is just a visual shorthand. If you ever see a "blue" vein during surgery, something is very, very wrong. This color-coding is a double-edged sword; it helps you learn the "road map" but it makes you feel totally lost when you see the "real road."

📖 Related: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

The Complexity of the Nervous System

If you want to feel truly overwhelmed, look at a map of the cranial nerves.

There are twelve of them. They emerge directly from the brain, skipping the spinal cord for the most part. They control everything from your ability to taste a lemon to your heart rate. Anatomy pictures of the human body usually struggle here. The "wires" are so thin and intertwined that even the best digital renders look like a bowl of spaghetti.

The Vagus nerve alone travels from the brainstem all the way down to the colon. It's the "body's superhighway." When people talk about "gut feelings," they aren't being metaphorical. They are talking about a physical nerve connection that is clearly visible in any decent anatomical plate.

Moving Toward a More Diverse Anatomy

One of the biggest criticisms of modern medical illustration is its lack of diversity. For decades, the "default" human in anatomy pictures was a muscular, 160-pound white male.

This isn't just a social issue; it’s a clinical one.

Dermatology, for example, has long struggled with showing how rashes or conditions appear on different skin tones. A "red" rash looks very different on dark skin. Thankfully, things are shifting. Projects like Mind the Gap by Malone Mukwende are creating new anatomical and clinical libraries that reflect the actual global population. We are finally seeing anatomy pictures that look like the people they are meant to heal.

Practical Steps for the Curious

If you’re trying to learn your own anatomy or just want to be a more informed patient, don’t just scroll through Google Images. Use professional-grade resources that provide context.

- Download "Complete Anatomy" or "BioDigital": These are the modern standards. They allow you to toggle layers on and off. You can see just the skeletal system, then "grow" the muscles over it.

- Check the Source: If an image doesn't credit a medical illustrator or a university, be skeptical. Many "infographic" style anatomy pictures are riddled with errors—like kidneys placed too high or muscles attached to the wrong bones.

- Look for "Radiological Anatomy": This is the bridge between a drawing and a real body. It shows you what an X-ray or MRI actually looks like compared to the textbook version.

- Understand "Origin and Insertion": When looking at a muscle, don't just look at the "bulge." Look at where it starts (origin) and where it ends (insertion). That tells you exactly what that muscle does. If it doesn't cross a joint, it doesn't move that joint. Period.

The next time you see anatomy pictures of the human body, remember you’re looking at a translation. It's a map, not the territory. Use it to find your way around, but don't be surprised if your own "terrain" is a little different.

To deepen your understanding, start by identifying the major landmarks on your own body. Feel the bony prominence of your ulna at the elbow or the "ASIS" (the hip bone point in front). Locating these physical markers while looking at a high-quality anatomical diagram bridges the gap between abstract art and your actual physical existence. This tactile feedback is how the best clinicians master the human form, and it’s the most effective way to make sense of the complex imagery inside a medical text.