Look at your hand. Specifically, look at your thumb. It’s shorter than your fingers, it’s stubby, and honestly, it looks a bit out of place compared to the elegant tap-tap-tap of your other four digits. But without the specific anatomy of the thumb, you wouldn't be able to hold a pen, button your shirt, or—let’s be real—scroll through this article on your phone. It is the undisputed MVP of human dexterity.

Most people think of the thumb as just another finger. It isn't. Not even close. From the way the bones are shaped to the unique "saddle" joint at the base, the thumb is a structural masterpiece that separates us from almost every other creature on Earth.

The Saddle Joint: Where the Magic Happens

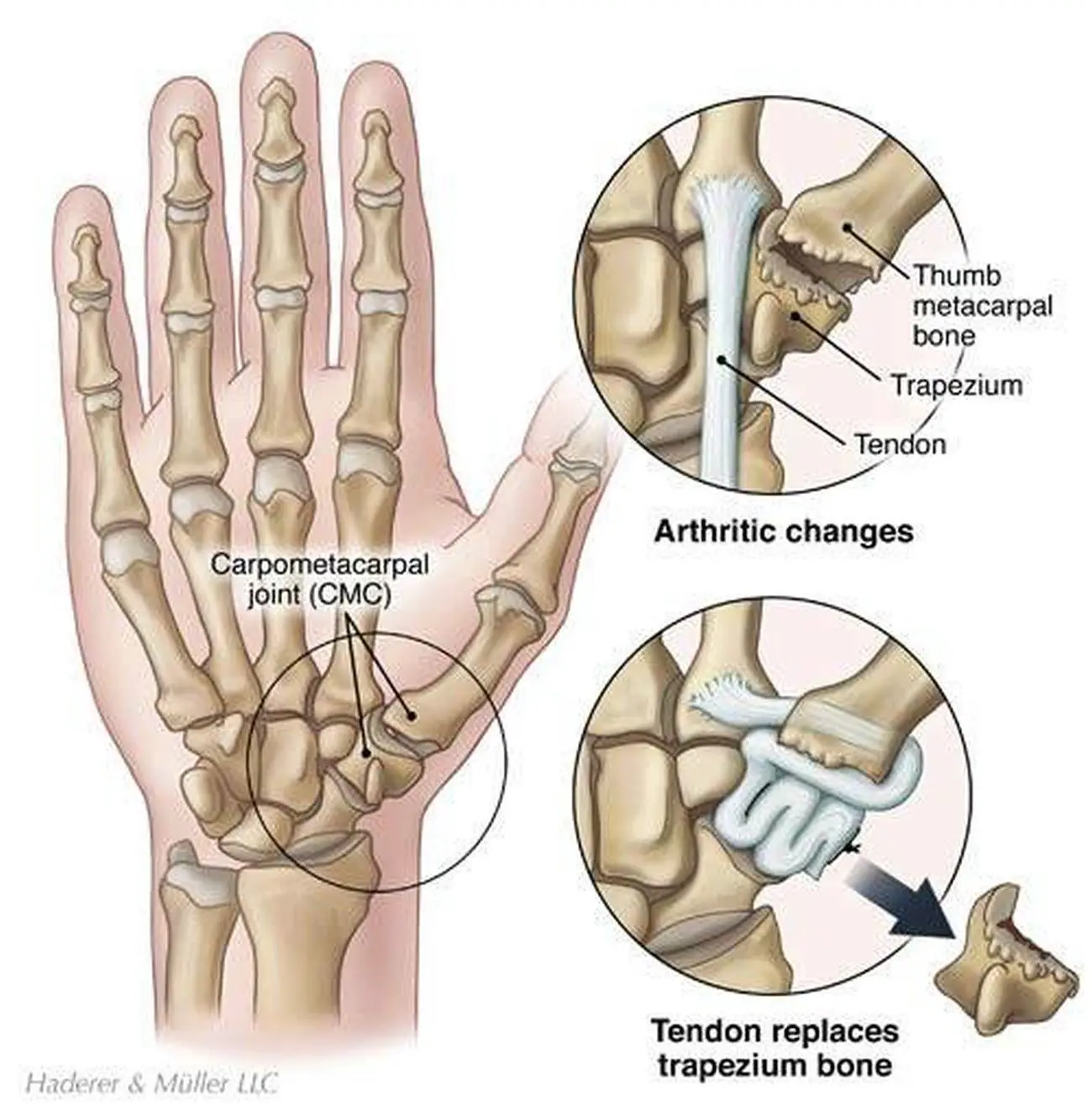

The secret sauce of thumb movement is the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint. This is located right at the base of your thumb, near your wrist. Unlike the joints in your fingers, which mostly just bend and straighten like a door hinge, the CMC joint is a saddle joint.

📖 Related: The Notochord Explained: Why This Little Rod Is the Secret to Your Entire Body

Think of two saddles nested together. One sits on top of the other, perpendicular. This unique geometry allows for a massive range of motion. You can move your thumb in, out, across your palm, and—most importantly—you can rotate it. This rotation is what allows for opposition.

Opposition is the ability to touch the tip of your thumb to the tips of your other fingers. If you try to do this with your pinky and ring finger without using your thumb, you’ll realize how impossible it is. Dr. Susan Mackinnon, a renowned nerve surgeon, often highlights that the median nerve's primary "job" in the hand is ensuring this oppositional strength remains intact. Without that saddle joint, we’d be stuck with "power grips" only, like a monkey swinging from a branch, rather than the "precision grips" needed to perform surgery or play the guitar.

More Than Just Two Bones

If you feel your fingers, you’ll notice three distinct sections (phalanges). Your thumb only has two: the proximal phalanx and the distal phalanx.

Wait.

If it only has two bones, why does it feel so long and mobile? That’s because the first metacarpal—the bone inside your palm—is often mistaken for a finger bone because it moves so freely. In your other fingers, the metacarpals are locked tight into the palm by ligaments. In the thumb, that first metacarpal is a wild card. It’s loose. It’s mobile. It’s basically acting like a third phalanx that lives inside your hand.

The Muscles That Do the Heavy Lifting

The anatomy of the thumb involves nine individual muscles. That is an absurd amount of "engine" for such a small part of the body. These muscles are controlled by three different major nerves: the median, radial, and ulnar nerves.

- The Thenar Eminence: That meaty bump at the base of your thumb? That’s the thenar eminence. It’s a group of three muscles (abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, and opponens pollicis) that allow you to bring the thumb across the palm.

- The Hitchhiker Muscle: The extensor pollicis longus is what lets you give a thumbs-up. It runs all the way from your forearm, through a little "pulley" on your wrist called Lister's tubercle, and attaches to the tip of your thumb.

- The Powerhouse: The adductor pollicis. This is the muscle that lets you pinch things really hard. Interestingly, it's the only thumb muscle supplied by the ulnar nerve.

Ever wonder why your hand hurts after a long day of yard work or typing? It’s usually these nine muscles working overtime to stabilize a joint that is inherently "loose" so it can stay mobile.

Why the Anatomy of the Thumb Frequently Breaks

Because the thumb is so mobile, it’s also prone to wear and tear. Basal joint arthritis is one of the most common issues people face as they age. Since the CMC joint is constantly rotating and pivoting, the cartilage wears down faster than in the "hinge" joints of the fingers.

Then there’s Skier’s Thumb. This happens when you fall and your thumb gets pulled back away from the palm, tearing the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL). It’s called Skier’s Thumb because people often fall while holding a ski pole, which acts as a lever to snap the ligament.

Physical therapists, like those specializing in Hand Therapy (CHT), focus heavily on the "stable arch" of the thumb. When the anatomy of the thumb is compromised—whether by a ligament tear or simple inflammation like De Quervain’s tenosynovitis—the entire functionality of the hand drops by about 40% to 50%. You don't realize how much you use it until you have to tape it up and try to open a jar of pickles without it.

Evolution and the "Pre-Thumb"

Humans aren't the only ones with thumbs, but we are the only ones with this thumb. Chimpanzees have opposable thumbs, but theirs are much shorter and placed further down the wrist. They can't easily perform a "pad-to-pad" pinch.

Archaeological findings, such as the Australopithecus africanus fossils, show that our ancestors began developing longer thumbs and shorter fingers millions of years ago. This shift likely happened because those who could make better tools survived. The anatomy of the thumb literally shaped human history.

Taking Care of Your Thumbs

If you’re feeling a dull ache at the base of your hand, you’re likely overstressing the CMC joint. Texting with your thumbs for six hours a day isn't exactly what evolution had in mind.

- Use your voice. Give your thumbs a break by using speech-to-text for long messages.

- Stretch the webbing. Gently pull your thumb away from your palm to stretch the adductor muscle. This gets tight and can pull the joint out of alignment.

- Check your grip. If you're holding your phone so tight your knuckles turn white, stop. Get a "pop-socket" or a ring holder. It changes the ergonomics and takes the pressure off the saddle joint.

- Ice the base. If the "meaty part" of your thumb is sore after a workout, ice the wrist area, not just the tip of the thumb. That’s where the tendons and the main joint live.

The anatomy of the thumb is a weird, beautiful mix of redundancy and precision. It’s got more muscles than it seems to need and a joint that shouldn't work as well as it does. Treat it well. It’s the only reason you’re not still trying to crack nuts with a rock.