Most of us think of our stomach as this big, hollow balloon sitting right in the middle of our gut, waiting for a cheeseburger to land. It's just a pit, right? Honestly, that is a massive oversimplification. If you actually look at the anatomy of the stomach, it’s a high-pressure chemical plant, a muscular grinder, and a sophisticated endocrine organ all rolled into one. It’s not even where you think it is. Most people point to their belly button when they say their stomach hurts, but the actual organ sits much higher up, tucked under the ribs on the left side, hiding behind the liver.

It’s about the size of two fists clenched together when it's empty. But it’s stretchy. Incredibly stretchy.

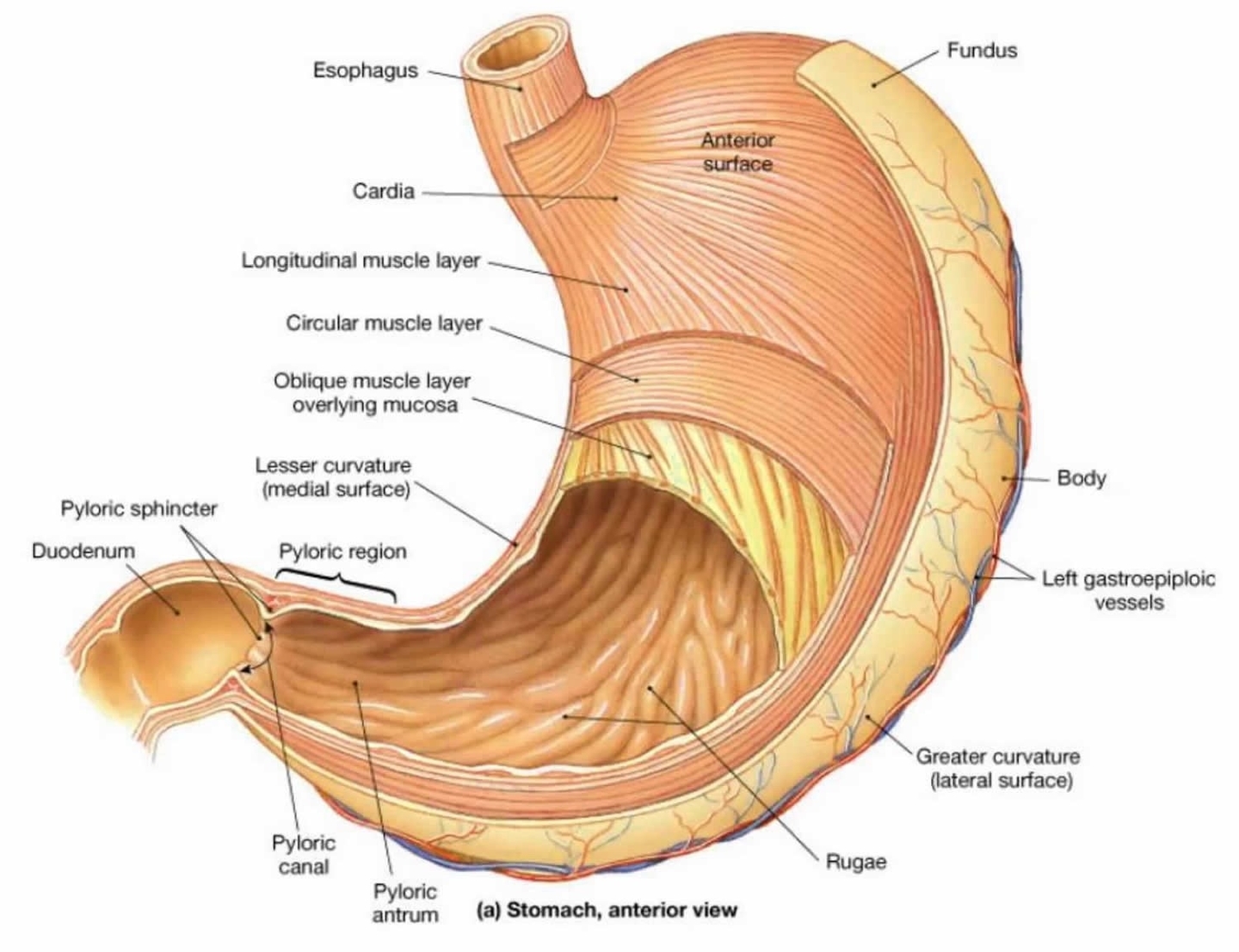

The stomach is J-shaped. That curve isn’t just for aesthetics; it’s functional. Doctors like Dr. Ashkan Farhadi, a gastroenterologist at MemorialCare, often point out that the stomach’s specific shape and its distinct regions—the cardia, fundus, body, antrum, and pylorus—work like a relay team. If one part fails, the whole system of digestion falls apart. You’ve probably heard of the "stomach flu," but that's usually an intestinal issue. When we talk about the stomach’s true anatomy, we’re talking about the gateway to the rest of your body.

The five zones you didn’t know you had

The stomach isn't just one big room. It’s divided into specialized zones. First, there’s the cardia. This is the entryway. It’s the tiny area where the esophagus meets the stomach. There’s a valve here called the Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES). If that valve gets lazy, you get acid reflux. It’s basically a security guard that’s supposed to stay closed once the food passes through.

Then you have the fundus. This is the upper, rounded part. It’s often filled with gas. If you've ever felt a weird pressure under your ribs after drinking a soda, that’s your fundus doing its thing. It collects digestive gases and stores undigested food for a bit before the heavy lifting starts.

Next is the body or the corpus. This is the "main event." It’s the largest region where the most chemical breakdown happens.

Down at the bottom, things get mechanical. The antrum is the lower part of the stomach that holds the food until it’s ready to be passed into the small intestine. It’s heavily muscled. It grinds food into a paste called chyme. Finally, the pylorus is the exit gate. It has a thick muscular ring called the pyloric sphincter that controls exactly how much food leaves at once. It doesn't just dump everything; it lets out about a teaspoon at a time. It’s a very picky bouncer.

✨ Don't miss: 2025 Radioactive Shrimp Recall: What Really Happened With Your Frozen Seafood

The layers of the wall (It's like an onion)

If you were to take a cross-section of the stomach wall, you’d see four distinct layers. It’s thick. It has to be. You are essentially carrying a bag of acid inside your body that is strong enough to dissolve metal.

The innermost layer is the mucosa. This is where the magic (and the pain) happens. It’s covered in tiny holes called gastric pits. These pits lead to gastric glands that pump out hydrochloric acid and enzymes like pepsin. To keep the acid from eating the stomach itself, the mucosa produces a thick layer of alkaline mucus. It’s a literal shield. When that shield fails, you get an ulcer. It’s a delicate balance.

Outside the mucosa is the submucosa. This layer is packed with blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. It supports the mucosa and keeps the blood flowing so the tissue can repair itself constantly.

Then comes the muscularis externa. Most organs have two layers of muscle. The stomach has three. It has circular, longitudinal, and oblique layers. This triple-threat allows the stomach to churn, fold, and squeeze in multiple directions. It’s not just pushing food down; it’s literally pulverizing it.

The outermost layer is the serosa. It’s a smooth, slippery membrane that reduces friction. Your organs are constantly moving against each other. Without the serosa, every time you took a breath or digested a meal, your organs would chafe.

The chemistry of the "Pit"

We need to talk about the acid. Gastric acid is mostly hydrochloric acid (HCl). On the pH scale, it sits somewhere between 1.5 and 3.5. That is incredibly acidic. If you dropped a piece of zinc into it, it would dissolve.

🔗 Read more: Barras de proteina sin azucar: Lo que las etiquetas no te dicen y cómo elegirlas de verdad

Why so intense? Two reasons. First, it kills bacteria. Most of the stuff you eat is covered in microbes that would love to colonize your gut. The stomach is a sterilization chamber. Second, the acid activates enzymes. There’s an enzyme called pepsinogen that is totally useless on its own. But when it hits that acid, it turns into pepsin, which is the primary tool for breaking down proteins.

There is also something called Intrinsic Factor. This is a glycoprotein produced by the parietal cells in the stomach lining. Without it, your body cannot absorb Vitamin B12 in the small intestine. You could eat all the B12 in the world, but if your stomach anatomy isn't functioning right to produce Intrinsic Factor, you’ll end up with pernicious anemia. This is a common issue for people who have had gastric bypass surgery or suffer from chronic gastritis.

The stomach-brain connection is real

The stomach is sometimes called the "second brain," though that usually refers to the entire enteric nervous system. But the stomach specifically is wired directly to your cranium via the vagus nerve.

This isn't just a one-way street where the brain tells the stomach to get hungry. It’s a constant dialogue. When the stomach is empty, it produces a hormone called ghrelin. This is the "hunger hormone." It travels through your blood and tells your hypothalamus, "Hey, we’re empty down here. Go find a taco."

Conversely, when the stomach stretches, mechanoreceptors in the muscular walls send signals back up the vagus nerve to tell the brain you’re full. This is why eating slowly works for weight loss; it takes about 20 minutes for those "stretch" signals to actually register in your brain. If you bolt your food, your stomach is screaming "I'm full!" but the brain hasn't checked its messages yet.

What people get wrong about "Stomach Capacity"

There’s a myth that if you eat a lot, you "stretch out" your stomach permanently. Sorta true, but mostly false. The stomach is made of rugae—these are folds in the lining that look like a wrinkled carpet. When you eat, these folds flatten out, allowing the stomach to expand from about 50ml to over 4 liters.

💡 You might also like: Cleveland clinic abu dhabi photos: Why This Hospital Looks More Like a Museum

Once the food moves on, the stomach returns to its resting size. It’s an elastic organ. However, chronic overeating can change the "threshold" of when you feel full. The anatomy doesn't necessarily change permanently, but the signaling does.

Another misconception is that the stomach is where all digestion happens. Nope. The stomach is mostly for protein breakdown and mechanical churning. Most of your nutrients—fats, carbs, vitamins—are actually absorbed in the small intestine. The stomach is just the prep cook that gets the ingredients ready for the chef.

When the anatomy fails: Ulcers and Hernias

Sometimes the system breaks. Gastritis is an inflammation of that inner mucosa layer. Often, it's caused by a bacteria called Helicobacter pylori. For a long time, doctors thought ulcers were caused by stress or spicy food. Then, in the 1980s, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren proved it was a bacterial infection. Marshall actually drank a beaker of the bacteria to prove his point. He got an ulcer, treated it with antibiotics, and eventually won a Nobel Prize. Total legend.

Then there’s the Hiatal Hernia. This happens when the top part of the stomach pokes through the diaphragm into the chest cavity. Because the diaphragm usually helps keep the LES valve closed, a hernia makes acid reflux almost inevitable. It’s an anatomical "glitch" that affects millions, often caused by heavy lifting or simply aging.

Actionable insights for a healthier stomach

Understanding the anatomy of the stomach means you can take better care of it. It’s not just about what you eat, but how you treat the "machinery."

- Chew your food. Seriously. Your stomach has three layers of muscle, but it doesn't have teeth. The more work you do in your mouth, the less stress you put on the antrum to grind things down.

- Watch the NSAIDs. Drugs like ibuprofen and aspirin can inhibit the production of prostaglandins, which are necessary for maintaining that protective mucus shield. Too many of them can lead to "chemical" gastritis.

- Don't lay down immediately after eating. Remember the bouncer (the LES) at the top of the stomach? Gravity helps keep the acid down. When you lay flat, you’re making it way easier for acid to slip past the cardia and burn your esophagus.

- Manage your stress. Since the vagus nerve connects your brain and stomach, high stress can literally change the rate of acid production and how fast your stomach empties. "Nervous stomach" isn't just a phrase; it's a physiological response.

- Hydrate, but don't drown your meals. A little water helps digestion, but drinking massive amounts of liquid during a meal can dilute the gastric juices, making the pepsin less effective at breaking down that steak.

The stomach is a rugged, sophisticated organ that handles incredible abuse. It’s the only part of your body designed to hold corrosive acid and grinding force simultaneously. Treat it like the specialized chemical plant it is, rather than just a trash can for calories. Focus on smaller, more frequent meals if you struggle with reflux, and always pay attention to "fullness" signals—they are the anatomical sensors doing their job to keep your entire system in balance.