Ever try to scratch that one specific spot right between your shoulder blades? You know the one. It’s infuriating. That tiny patch of skin represents the great mystery of our own existence: the posterior chain. Most of us spend our lives staring at the front of ourselves in the mirror, obsessing over abs or jawlines, but the anatomy of the human body back view is actually where the real "engine" of the human machine lives. It’s the side that carries the weight of your day, literally and metaphorically.

Honestly, it’s kinda weird how little we know about our backs until they start hurting. We treat the posterior side like the "back of the house" in a restaurant—messy, functional, and hidden away. But if you actually look at the architecture back there, it’s a masterpiece of biological engineering. From the massive sweep of the latissimus dorsi to the intricate, tiny rotatores that hug the spine, it's a layered system that keeps us from collapsing into a puddle on the floor.

The Spine is the Anchor, Not Just a Support Beam

When people think about the anatomy of the human body back view, they usually picture the spine as a straight pole. It isn’t. If your spine were straight, you’d walk like a glitchy robot and probably break something the first time you tried to jump. It’s a series of elegant curves—the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar curvatures—that act like a literal spring.

The "back view" gives us the best look at the vertebral column’s protective role. You’ve got 33 vertebrae in total, though the ones at the bottom (the sacrum and coccyx) are fused together. The ones that matter most for your daily movement are the 24 mobile ones. Each one is separated by an intervertebral disc. Think of these like jelly donuts. When you sit hunched over a laptop for eight hours, you’re basically squishing one side of the donut, forcing the "jelly" (the nucleus pulposus) to bulge out the other side. This is why "slipped" or herniated discs happen. It’s not a mystery; it’s just physics.

The Scapula: The Floating Bones

Take a second and reach your arm across your chest. Feel that bone sliding around on your back? That’s your scapula, or shoulder blade. Most people don't realize that the scapula isn't bolted onto the ribs. It "floats" in a bed of muscle. This is called the scapulothoracic joint, though it’s not a true joint in the sense that bone meets bone.

This design is what allows humans to throw things with such terrifying accuracy. Because the scapula can rotate, tilt, and slide, your arm has a range of motion that most mammals can only dream of. But this mobility comes at a price. Because it’s held in place by muscles like the serratus anterior and the trapezius, if those muscles get weak or tight, your whole shoulder "mechanics" go out the window. You get "winging," where the bone pokes out like a bird's wing, which is a sign that the stabilizing muscles have basically clocked out for the day.

A Landscape of Muscle Layers

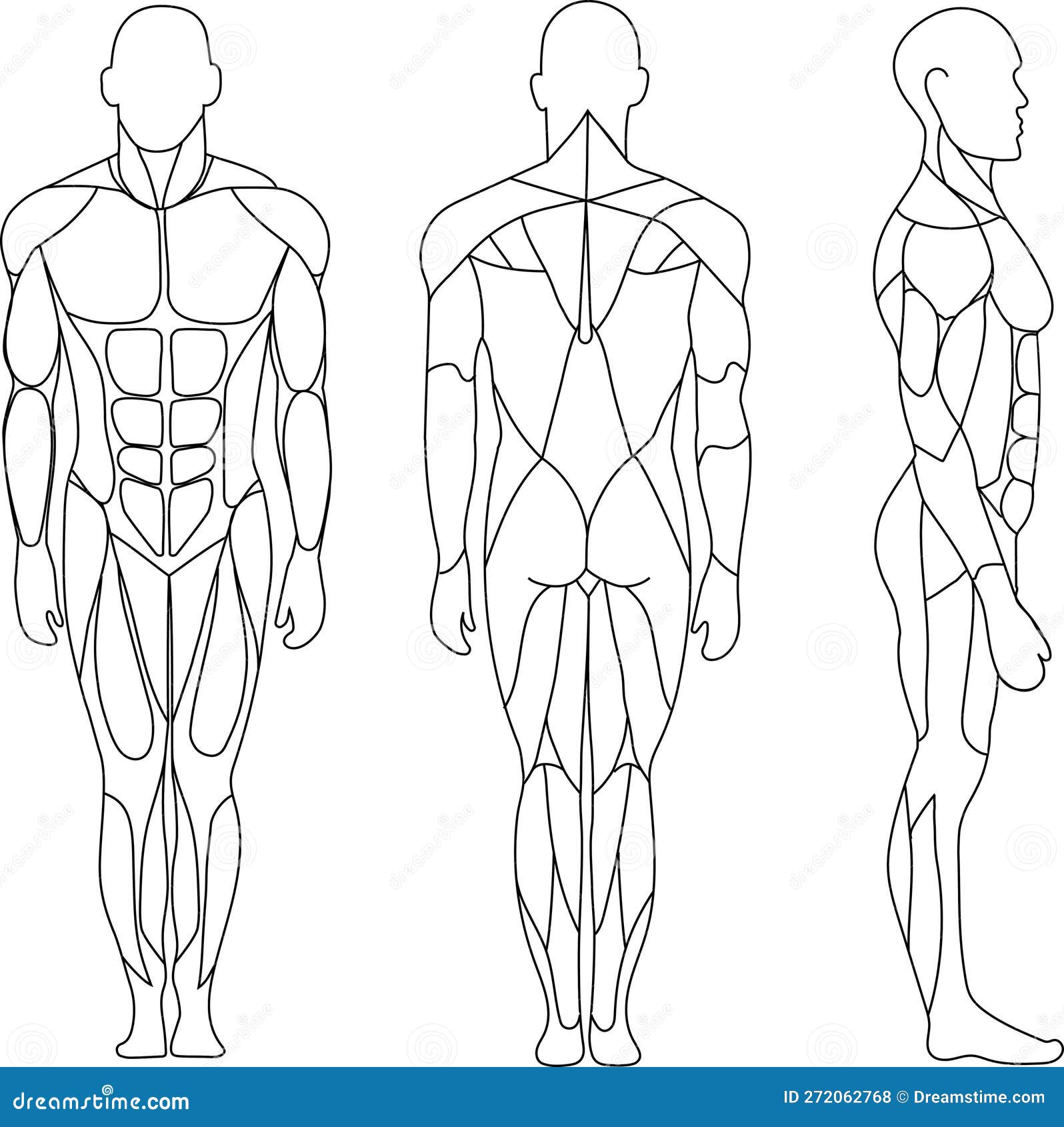

The anatomy of the human body back view is often taught in three layers: superficial, intermediate, and deep. It’s like a biological lasagna.

📖 Related: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

The superficial layer is what bodybuilders care about. You’ve got the trapezius, which is that diamond-shaped muscle that runs from the base of your skull down to the middle of your back and out to the shoulders. People think "traps" are just the meaty bits next to your neck, but the lower fibers of the trapezius are actually crucial for pulling your shoulder blades down and back. Without them, you’d look like you’re constantly shrugging in confusion.

Then you have the latissimus dorsi. These are the "wings." They are the largest muscles of the upper body. Fun fact: the "lats" actually attach to the humerus (the upper arm bone) but originate all the way down at the lower spine and pelvis. This means when you do a pull-up, your lower back is technically helping your arms. It’s all connected.

The Hidden Intermediate Layer

Underneath the big showy muscles, things get technical. We have the rhomboids (major and minor), which sit between the spine and the scapula. When you "pinch" your shoulder blades together, that’s the rhomboids working.

There are also the serratus posterior muscles. Honestly, most people—even some trainers—forget these exist. They help with respiration. They’re tiny, thin muscles that assist in lifting or depressing the ribs when you breathe. It’s a reminder that the back view isn't just about movement; it’s about survival. Every breath you take involves a coordinated dance of posterior muscles.

The Deep Muscles: The "Erectors"

The real heroes are the erector spinae group. This is a bundle of three muscles: the iliocostalis, longissimus, and spinalis. They run vertically along the spine. If you see two "pillars" of muscle on either side of someone’s spine, those are the erectors. Their job is simple but exhausting: keep you upright against the relentless pull of gravity.

Then there’s the multifidus. This muscle is tiny, but it’s a powerhouse of stability. Studies, like those from the Journal of Anatomy, have shown that in people with chronic low back pain, the multifidus is often "atrophied" or replaced by fatty tissue. It’s the muscle that should fire before you even move your arm to stabilize the spine. If it’s sleepy, your spine is basically unprotected during movement.

👉 See also: Why Sometimes You Just Need a Hug: The Real Science of Physical Touch

The Gluteal Region: The Engine Room

We can’t talk about the back view without talking about the butt. The gluteus maximus is the largest and heaviest muscle in the human body. Why? Because we walk on two legs. Great apes have glutes, but nothing like ours. Our glutes are designed to keep us upright and propel us forward.

But here’s the problem: we sit on them. All day.

This leads to what some physical therapists call "Gluteal Amnesia." Basically, the muscle forgets how to fire because it’s being crushed under your body weight for 10 hours a day. When the glutes stop working, the lower back (the lumbar spine) has to take over the job of stabilizing the body. The lumbar spine isn't built for that. It’s built for stability, not heavy lifting. This is why 80% of adults experience back pain at some point. It’s usually not a "back" problem—it’s a "lazy butt" problem.

The Pelvic Tilt Mystery

Looking at the anatomy of the human body back view reveals a lot about someone's posture via the pelvis. If you see someone whose lower back arches deeply and their butt pokes out, they likely have an "anterior pelvic tilt." This usually means their hip flexors (on the front) are too tight and their hamstrings and glutes (on the back) are too weak.

Conversely, a "flat back" or posterior tilt makes it look like the person has no glutes at all. Both positions put massive shearing force on the spinal discs. The "back view" is essentially a diagnostic map of how someone spends their time. You can tell if someone is a cyclist, a weightlifter, or a software engineer just by looking at the tension patterns in their posterior chain.

The Fascial Connection

We talk about muscles like they are separate entities, but they are actually wrapped in a giant web of connective tissue called fascia. On the back, the most important piece is the thoracolumbar fascia. It’s a large, diamond-shaped patch of white, silvery tissue in the lower back.

✨ Don't miss: Can I overdose on vitamin d? The reality of supplement toxicity

Think of it as a natural weightlifting belt. It connects the lats, the glutes, and the internal obliques. When you tension this fascia (by bracing your core), it actually helps stabilize the spine. This is why "bracing" is so important when lifting heavy groceries or a barbell. You’re using your internal architecture to create a rigid structure.

What Most People Get Wrong About Back Pain

The biggest misconception is that if your back hurts, the problem is in your back.

In the world of anatomy, the back is often the victim, not the criminal. Tight hamstrings pull on the ischial tuberosity (the sit bones), which tilts the pelvis and strains the lower back. Tight lats can pull the shoulders forward, causing the upper back muscles to stay in a constant, painful stretch.

Another huge myth? That you should "stay still" if your back hurts. Unless there’s a fracture or a severe acute injury, movement is usually the medicine. The structures in the anatomy of the human body back view thrive on blood flow and varied loading. The discs in your spine don't have their own blood supply; they get nutrients through a process called "imbibition," which is basically a fancy word for being squeezed and released through movement. If you don't move, your discs don't eat.

Practical Insights for Posterior Health

Since you can't see your back, you have to feel it. Improving your "back view" isn't just about aesthetics; it's about making sure your body doesn't fall apart by age 50.

- The 30-Minute Rule: Your fascia begins to "set" after about 30 minutes of stillness. Stand up, reach for the ceiling, and do a gentle "cat-cow" stretch to keep the thoracolumbar fascia hydrated.

- The Pull-to-Push Ratio: For every chest exercise you do (like pushups), do two "pull" exercises (like rows). This counteracts the "internal rotation" of the shoulders that comes from typing and driving.

- Glute Activation: Before you go for a walk or a workout, do some glute bridges. Remind your brain that your butt exists. It will take the load off your lumbar spine instantly.

- Check Your Hips: If your lower back is chronically tight, stop stretching your back. Start stretching your hip flexors (the front of your thighs). Often, the back is tight because it's trying to fight the tension coming from the front.

The anatomy of the human body back view is a complex, beautiful system of levers and pulleys. It's the foundation of human movement. We might not see it in the mirror every morning, but it's the part of us that carries the world. Treat it with a little respect, move it often, and maybe—just maybe—buy a long-handled back scratcher for those hard-to-reach spots.

To truly master your posterior health, start by assessing your standing posture in a side-profile mirror. Look for the "plumb line" that should run through your ear, shoulder, hip, and ankle. If your head is forward or your pelvis is tilted, your back muscles are working overtime just to keep you from tipping over. Correcting these small misalignments is the first step toward a pain-free life and a more functional posterior chain.