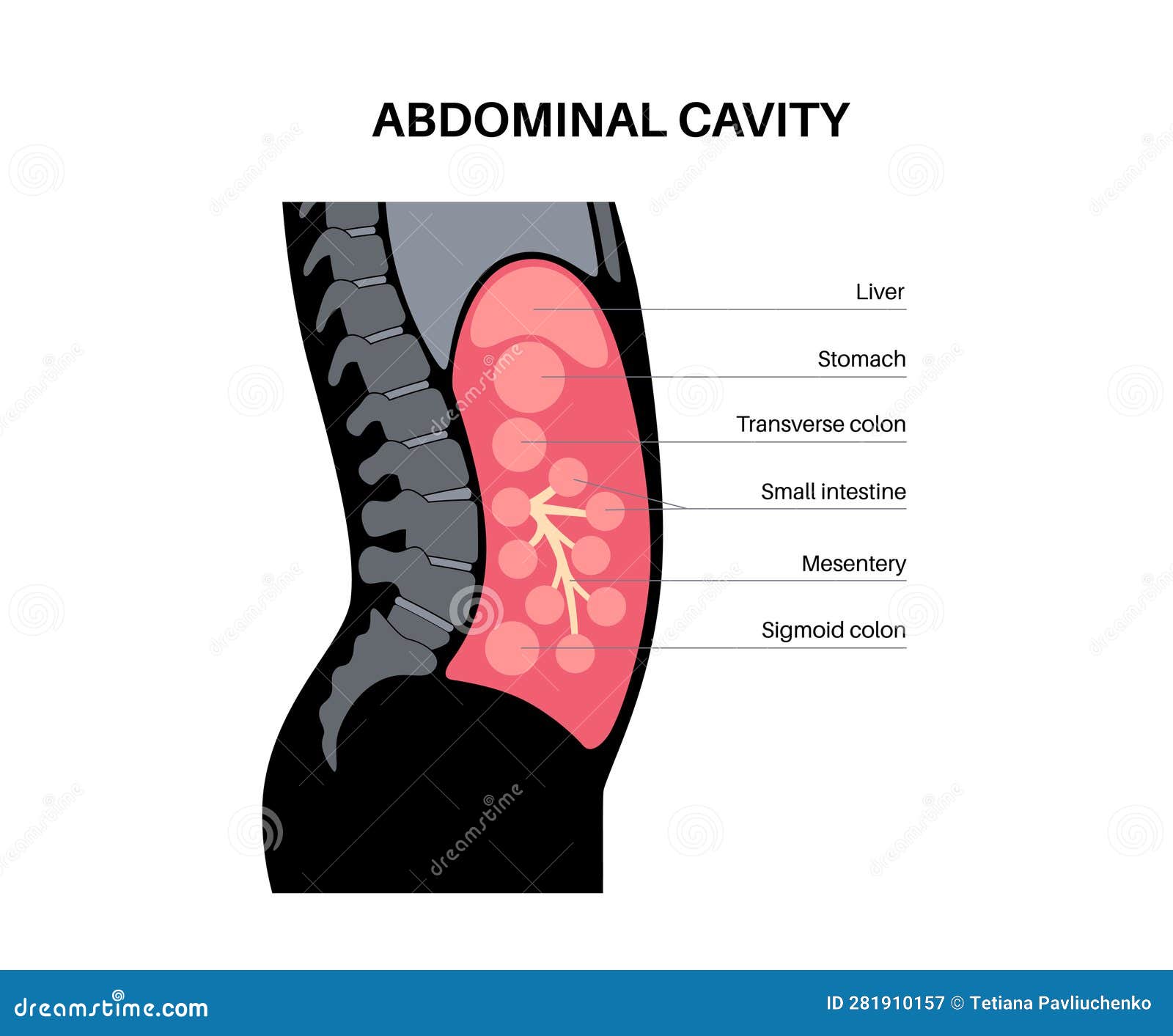

You probably think of your "stomach" as one big, sloshy bag of acid right behind your belly button. Most people do. But if you actually peeled back the layers—which, honestly, is a pretty messy mental image—you’d find a space that is less like a single room and more like a high-density apartment complex in Manhattan. Everything is packed in tight. There isn’t a spare inch of "empty" space. This is the anatomy of the abdominal cavity, a complex, pressurized vault that houses most of your digestive system, your filtration units, and some of your most vital plumbing.

It’s crowded.

Think about the last time you ate a massive Thanksgiving dinner. Your abdomen didn't just expand because of the food; it expanded because the organs inside were competing for real estate. Your stomach pushed against your liver, your liver nudged your diaphragm, and your intestines got squeezed into the corners. It’s a miracle nothing breaks.

The Container: More Than Just Skin and Muscle

Before we talk about the "stuff" inside, we have to look at the box it comes in. The anatomy of the abdominal cavity isn't just a hole in your torso. It’s bounded at the top by the diaphragm—that dome-shaped muscle that keeps your lungs from squashing your liver—and at the bottom by the pelvic inlet. It’s a pressurized environment. If you’ve ever had "the wind knocked out of you," you’ve experienced a sudden change in this internal pressure.

The walls are mostly muscle. You’ve got the rectus abdominis (the "six-pack"), the obliques on the sides, and the transversus abdominis, which acts like a natural weightlifting belt. But the real magic is the peritoneum.

🔗 Read more: Images of the Mitochondria: Why Most Diagrams are Kinda Wrong

Imagine taking a giant piece of Saran Wrap, coating it in a bit of oil, and lining the inside of a box with it. Then, take all the organs, wrap them in more Saran Wrap, and shove them inside. That’s the peritoneum. It’s a serous membrane that secretes a tiny bit of fluid so your organs can slide past each other without friction. Without this lubricant, every time you took a breath or twisted your torso, your guts would catch and tear. Doctors call the space between these layers the peritoneal cavity. It's technically a "potential space," meaning it's usually empty except for that thin film of fluid.

The Upper Floor: The Heavy Hitters

Right under your ribs on the right side sits the liver. It is huge. Honestly, it's surprisingly heavy, weighing about three pounds in an average adult. It’s the body’s chemical processing plant. To its left, tucked under the left ribs, is the stomach. This is where the confusion usually starts. People point to their lower belly and say "my stomach hurts," but your actual stomach is much higher up than you think.

Then there’s the pancreas, which is a bit of a recluse. It hides behind the stomach, tucked into the curve of the duodenum. It’s "retroperitoneal," which is a fancy medical term meaning it sits behind the main plastic wrap lining of the cavity. Because it's so deep, issues with the pancreas often feel like back pain rather than stomach pain. This is why surgeons sometimes hate dealing with it—it's hard to get to and it's incredibly fragile.

- The Spleen: A purple, fist-sized organ on the far left. It's like a blood filter and a graveyard for old red blood cells. It’s also incredibly delicate; a hard hit in a car accident can make it bleed like a faucet.

- The Gallbladder: A tiny green pouch under the liver. It stores bile. You don't technically need it, but you'll miss it if you eat a double cheeseburger after having it removed.

- The Kidneys: Also retroperitoneal. They sit against the back wall, protected by a thick layer of fat and the lower ribs.

The Great Tangled Mess: The Intestines

If you unspooled your small intestine, it would be about 20 feet long. How does 20 feet of tubing fit into a space the size of a basketball? Folding. Lots and lots of folding. The anatomy of the abdominal cavity solves this packing problem using the mesentery.

💡 You might also like: How to Hit Rear Delts with Dumbbells: Why Your Back Is Stealing the Gains

The mesentery was actually reclassified as a continuous organ by researchers like J. Calvin Coffey back in 2016. It’s not just "stuffing." It’s a double fold of peritoneum that attaches your intestines to the back wall of your abdomen. It’s like a fan. It holds the guts in place so they don't tie themselves into knots while still allowing them enough wiggle room to move food along. It also carries all the blood vessels and nerves to the bowel. If you lose blood flow through the mesentery, the gut dies. It’s that simple and that terrifying.

Then you have the large intestine, or colon. It frames the small intestine like a picture frame. It starts at the bottom right with the cecum—where that useless little tail, the appendix, hangs off—goes up (ascending colon), across (transverse colon), down (descending colon), and finally loops into the S-shaped sigmoid colon before hitting the rectum.

What Most People Get Wrong About Abdominal Pain

Because everything is so packed together, your brain is actually pretty bad at telling you exactly where pain is coming from. This is called "referred pain."

If your gallbladder is inflamed, you might feel a sharp pain in your right shoulder blade. Why? Because the nerves that go to the gallbladder also happen to pass near the nerves for the shoulder. Your brain gets the signals crossed. Similarly, early appendicitis usually doesn't hurt in the lower right side. It starts as a dull ache right around the belly button. Only when the inflammation touches the outer lining of the anatomy of the abdominal cavity (the parietal peritoneum) does the pain shift to that classic "stabbing" sensation in the hip area.

📖 Related: How to get over a sore throat fast: What actually works when your neck feels like glass

Blood Flow: The High-Pressure Plumbing

Running straight down the back of the cavity is the abdominal aorta. It is the largest artery in your body. It’s about the thickness of a garden hose and it pulses with every heartbeat. If you are thin and lie flat on your back, you can actually see your pulse vibrating your stomach.

Next to it is the Inferior Vena Cava (IVC), which carries deoxygenated blood back up to the heart. The relationship between these vessels and the organs is tight. For example, the "Nutcracker Syndrome" happens when the left renal vein gets squeezed between the aorta and another artery, sort of like a nut in a nutcracker. It can cause all sorts of weird pelvic pain and blood in the urine, yet many people go years without a diagnosis because it's such a subtle anatomical quirk.

Practical Insights for Better Health

Understanding the anatomy of the abdominal cavity isn't just for med students. It changes how you treat your body.

- Core Strength Isn't Just for Abs: Strengthening your deep core (the transversus abdominis) helps maintain the internal pressure that protects your spine. Think of it as bracing the box that holds your organs.

- Watch the Visceral Fat: There are two types of fat. The stuff you can pinch (subcutaneous) and the stuff that lives inside the cavity around your organs (visceral). Visceral fat is metabolically active and inflammatory. It literally chokes your organs and increases the risk of heart disease more than "butt fat" or "thigh fat" ever could.

- Posture and Digestion: If you slouch, you are physically compressing your abdominal cavity. This reduces the space for your stomach to expand and can worsen acid reflux. Sitting up straight literally gives your organs room to breathe.

- Listen to the "Quiet" Signs: Because the cavity is pressurized, persistent bloating that doesn't go away with diet changes can sometimes be a sign of fluid buildup (ascites) or even tumors. If the "box" feels too full for no reason, it’s worth a scan.

The abdominal cavity is a masterpiece of spatial engineering. It’s a wet, dark, crowded, and highly efficient engine room. Every organ is tucked into its perfect niche, held in place by a complex web of membranes and supported by a muscular cage. Keeping that cage strong and the "stuffing" healthy is basically the secret to a long life.

To take care of this space, focus on movements that rotate the torso to keep the peritoneal surfaces sliding smoothly. Stay hydrated to maintain the quality of that serous fluid. And finally, pay attention to where you feel pain; your body is a map, and the anatomy of the abdominal cavity is the legend that helps you read it.