You probably think of your "stomach" as that general area between your chest and your hips. Most people do. But if you actually cracked the hood and looked inside, you’d see a chaotic, tightly packed masterpiece of engineering that makes a Swiss watch look like a pile of Legos. Honestly, your anatomy of abdominal organs isn't just a list of parts; it’s a high-stakes ecosystem where everything is fighting for a few millimeters of space.

It's crowded in there.

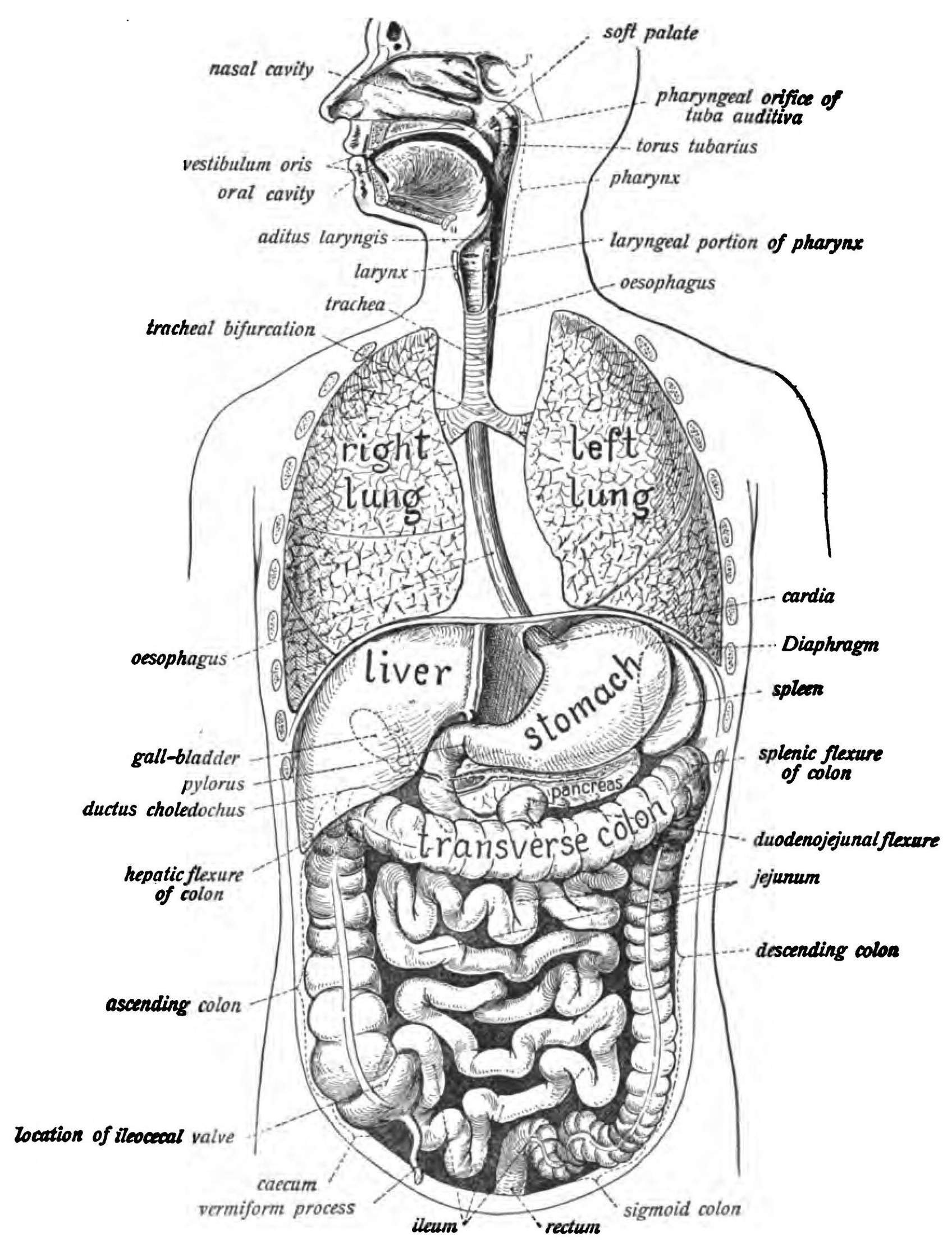

We’re talking about the peritoneal cavity, a space lined by a thin membrane called the peritoneum. It’s not just a bag. It’s a complex mapping system. When a doctor presses on your belly and asks "where does it hurt?", they aren't just poking you. They are mentally navigating through layers of fascia, fat, and muscle to figure out which specific neighbor in this crowded apartment complex is causing a ruckus.

👉 See also: Why You Need to Pat Yourself on the Back Way More Often

The Liver: The Heavyweight Champion You’re Ignoring

If your abdomen had a CEO, it would be the liver. Sitting right under your ribs on the right side, this thing is massive. It weighs about three pounds in an adult. It's reddish-brown, rubbery, and performs over 500 different functions. Basically, if your liver quits, the party is over immediately.

Most people know it processes alcohol, but its role in the anatomy of abdominal organs goes way beyond Saturday night regrets. It produces bile, which travels through the hepatic ducts to the gallbladder. It also stores glycogen for energy. Interestingly, the liver is the only organ that can actually regenerate. You can cut away a significant chunk, and as long as there’s enough healthy tissue left, it grows back. That’s some sci-fi level biology right there.

But here is the catch. Because it sits so high up, protected by the ribcage, you often can't feel it unless it's dangerously swollen. Surgeons like Dr. Sanjay Gupta have often pointed out that by the time you "feel" your liver, there's usually a serious problem. It’s a silent worker.

The Stomach is Smaller (and Higher) Than You Think

People point to their belly button when they say their stomach hurts. They're usually wrong. Your actual stomach—the J-shaped muscular sac—is tucked way up under the left side of your ribs.

It’s a mixer. It doesn’t just hold food; it pummels it with hydrochloric acid and enzymes like pepsin. The stomach wall is lined with deep folds called rugae. These let the stomach expand like an accordion when you decide to go for that second plate at the buffet. When it’s empty? It’s surprisingly small.

The "burn" of acid reflux happens at the gastroesophageal sphincter. This is a little muscular ring that acts like a one-way valve. If it gets lazy, stomach acid splashes up into the esophagus. Since the esophagus doesn't have the stomach’s specialized mucus lining, it literally gets chemical burns. That’s what you’re feeling. It has nothing to do with your heart, despite the name "heartburn."

The Pancreas and the "Retroperitoneal" Mystery

The pancreas is the shy one. It hides behind the stomach, tucked into the curve of the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). In the world of anatomy of abdominal organs, the pancreas is "retroperitoneal."

This means it sits behind the main abdominal lining.

Because of this location, pancreatic issues are notoriously hard to diagnose early. It has a dual personality. It’s an exocrine gland (shooting digestive enzymes into the gut) and an endocrine gland (pumping insulin and glucagon into the blood). If the pancreas gets inflamed—a condition called pancreatitis—the enzymes it usually sends to the gut start digesting the organ itself. It is exactly as painful as it sounds.

The Great Lengths of the Intestines

If you unspooled your small intestine, it would be about 20 feet long. Your large intestine is shorter, maybe 5 feet, but much wider.

Why the length? Surface area.

The small intestine is lined with millions of tiny, finger-like projections called villi. These villi are then covered in even smaller microvilli. If you flattened it all out, the absorptive surface of your gut would cover a tennis court. This is where the real work of living happens. This is where nutrients cross from the "outside" world (the tube of your gut) into your "inside" world (your bloodstream).

- The Duodenum: The first 10 inches. It’s the "mixing bowl" where bile and pancreatic juice meet food.

- The Jejunum: The middle child. Most nutrient absorption happens here.

- The Ileum: The final stretch. It picks up what’s left, like Vitamin B12 and bile salts.

Then you hit the cecum, the start of the large intestine. Attached to it is the appendix. For a long time, we thought the appendix was a useless evolutionary leftover. Recent research, including studies from Duke University, suggests it might actually be a "safe house" for good bacteria. When you get a massive bout of diarrhea that wipes out your gut flora, the appendix can reboot the system with the "backup" bacteria it’s been holding.

📖 Related: The One Arm Kettlebell Snatch: Why Your Shoulders Hate You and How to Fix It

The Kidneys: The Silent Filters in the Back

Technically, the kidneys are also retroperitoneal. They sit against the back muscles, right below the ribcage. Most people think they are lower down in the "small of the back," but they’re actually quite high up.

Each kidney contains about a million nephrons. These are microscopic filtering units. They process about 200 quarts of blood every single day to sift out roughly two quarts of waste products and extra water. They also control your blood pressure by releasing an enzyme called renin. It’s a delicate balance. If your blood pressure drops, the kidneys notice first.

Misconceptions and the "Referred Pain" Trap

One of the weirdest things about the anatomy of abdominal organs is that your brain is actually pretty bad at telling you where the pain is coming from. This is called referred pain.

Because the nerves for many internal organs enter the spinal cord at the same levels as nerves from the skin, the brain gets confused.

- Gallbladder pain often feels like a sharp stab in the right shoulder blade.

- Diaphragm irritation can make your neck hurt.

- A kidney stone might make your groin ache instead of your back.

This is why self-diagnosis is a nightmare. You might think you have a pulled muscle in your side when your spleen is actually signaling for help. The spleen, by the way, is a purple, fist-sized organ on the far left. It’s the "blood filter" and a major part of the immune system. You can live without it, but you'll be much more prone to certain infections.

👉 See also: Lemon Balm Tea Leaves: What Most People Get Wrong About This Ancient Stress-Reliever

Taking Care of the Inner Map

Understanding where things are helps you talk to your doctor, sure. But it also helps you realize how interconnected everything is. You can't affect one organ without touching the others.

If you want to keep this system running without a breakdown, you've got to focus on the basics of abdominal health:

- Hydration is non-negotiable. Your kidneys and your large intestine both rely on water to move waste. Without it, the large intestine steals water from your stool (hello, constipation) and the kidneys struggle to flush toxins.

- Fiber isn't just for old people. Soluble and insoluble fiber act like a broom for the intestines. It also feeds the bacteria in that "appendix safe house" we talked about.

- Watch the visceral fat. This isn't the fat you can pinch under your skin (subcutaneous). This is the fat that wraps around the organs themselves. Too much of it creates inflammation and puts physical pressure on the liver and pancreas, leading to metabolic issues.

- Listen to the "silent" signs. Chronic bloating, a change in bathroom habits that lasts more than two weeks, or yellowing of the eyes (jaundice) are the ways your organs scream for help since they don't have many pain receptors of their own.

Knowing your internal geography is the first step toward actually managing your health. Next time you feel a twinge, don't just call it a stomach ache. Think about the 20 feet of tubing, the chemical plant of the liver, and the hidden filters in your back. They’re all working overtime.

Next Steps for Your Health:

- Check your posture: Slumping actually compresses the abdominal cavity, which can slow down digestion and contribute to acid reflux. Stand up straight to give your organs "room to breathe."

- Audit your fiber intake: Most adults only get half of the recommended 25-30 grams. Start by adding one high-fiber food (like lentils or berries) to your lunch today.

- Track "referred" sensations: If you experience recurring pain in your shoulder or mid-back after eating fatty meals, mention it to your physician specifically, as it may be a gallbladder signal rather than a muscle strain.