You’re sprinting for the bus. Your lungs are screaming, your heart is thumping against your ribs like a trapped bird, and suddenly, your thighs feel like they’ve been injected with molten lead. That burn is biology in action. Specifically, it’s your body hitting the "emergency power" switch because it can't keep up with the demand for oxygen. Most of us think we need air to live—and we do—but at the cellular level, there's a backup plan. This backup plan is how we define anaerobic respiration in biology. It's the gritty, less efficient, but life-saving process of breaking down sugar for energy when oxygen is nowhere to be found.

It’s not just about tired gym-goers, though. Without this specific metabolic pathway, we wouldn't have sourdough bread, Swiss cheese, or a cold IPA. Entire ecosystems at the bottom of the ocean, tucked away in hydrothermal vents where the sun never shines and oxygen is a myth, rely entirely on anaerobic processes to exist.

The Chemistry of Life Without Air

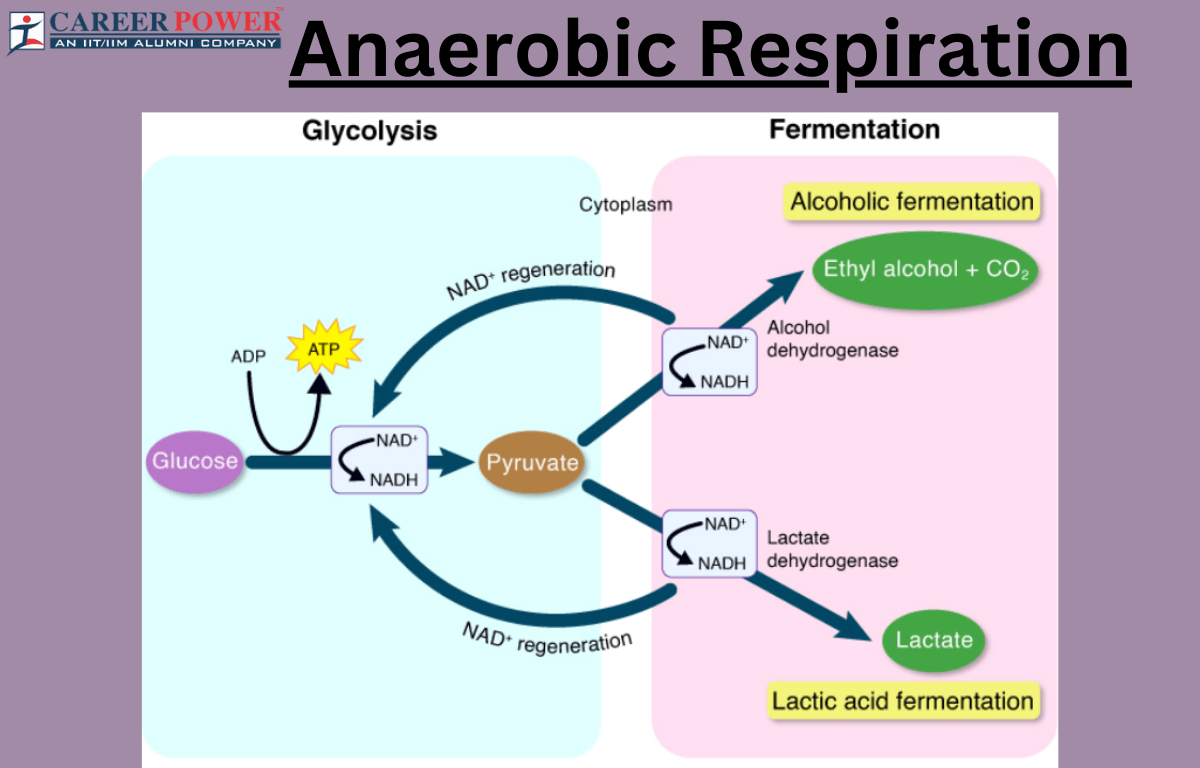

Let’s get into the weeds for a second. At its core, respiration is just a way to move electrons around to create ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which is the "currency" your cells use to do literally anything. In aerobic respiration, oxygen is the final electron acceptor. It’s the "clean" way to do business. But when you define anaerobic respiration in biology, you're looking at a system that swaps oxygen for something else—like sulfate or nitrate—or simply stops short and produces byproducts like lactic acid or ethanol.

Think of it like a car engine. Aerobic respiration is like a high-end Tesla; it’s efficient and clean. Anaerobic respiration is more like an old, beat-up generator. It’s loud, it’s messy, it leaves a lot of exhaust behind, but when the power goes out, you’re glad you have it.

The Human Side: Lactic Acid Fermentation

When you’re pushing your body to the limit, your muscles enter a state called hypoxia. There isn't enough oxygen to go around. To keep your muscles moving, your cells start converting pyruvate—a product of glycolysis—into lactic acid. This is why you feel that sharp, localized fatigue.

Actually, for a long time, scientists like Archibald Hill (who won a Nobel Prize in 1922) thought lactic acid was just a waste product that caused muscle soreness for days. We now know that's not quite right. Lactic acid is actually a fuel source. Your body eventually shuttles it to the liver, where it gets turned back into glucose. It's a recycling program. The soreness you feel the day after a workout? That’s more likely tiny micro-tears in the muscle fibers, not the "acid" itself.

The Weird World of Obligate Anaerobes

Humans are "facultative." We can do both. But some organisms are "obligate." To them, oxygen is literally a poison.

💡 You might also like: Resistance Bands Workout: Why Your Gym Memberships Are Feeling Extra Expensive Lately

Take Clostridium botulinum. You might know it as the stuff in Botox, but in the wild, it lives in soil or poorly canned food. Because it thrives in environments with zero oxygen, it uses anaerobic respiration to survive. This is why dented cans are so dangerous; the vacuum inside is a five-star resort for these bacteria. They produce some of the most potent neurotoxins known to man, all because they’re just trying to breathe in an oxygen-free world.

Alcohol, Yeast, and the History of Civilization

We can’t talk about how we define anaerobic respiration in biology without mentioning yeast. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is basically the most important fungus in human history. When yeast cells find themselves in a sugary environment without much oxygen, they perform ethanol fermentation.

They take glucose and turn it into two things: ethanol (alcohol) and carbon dioxide ($CO_{2}$).

- The $CO_{2}$ makes bread rise.

- The ethanol makes beer, well, beer.

It’s a survival strategy for the yeast. By producing alcohol, they actually kill off competing bacteria in their environment that can't handle the toxicity. It’s chemical warfare via respiration.

How it Works: The Electron Transport Chain

In a "standard" anaerobic setup—the kind used by bacteria in deep-sea vents—they still use an Electron Transport Chain (ETC). This is a complex series of protein complexes located in the cell membrane.

$$C_{6}H_{12}O_{6} + 12KNO_{3} \rightarrow 6CO_{2} + 6H_{2}O + 12KNO_{2} + Energy$$

📖 Related: Core Fitness Adjustable Dumbbell Weight Set: Why These Specific Weights Are Still Topping the Charts

Instead of oxygen sitting at the end of the line to catch the electrons, they use minerals. Some bacteria "breathe" iron. Others use manganese or sulfur. This is why salt marshes and swamps often smell like rotten eggs. That's hydrogen sulfide gas ($H_{2}S$), a direct byproduct of bacteria using sulfate instead of oxygen to power their tiny lives.

Why Efficiency Matters

Efficiency is the big catch. Aerobic respiration is a gold mine, producing about 36 to 38 ATP molecules per glucose molecule. Anaerobic respiration? It usually nets you a measly 2 ATP.

It’s a massive trade-off.

You get energy now, but you get very little of it, and you create a mess you have to clean up later. For a single-celled organism in a swamp, 2 ATP is plenty. For a 200-pound human trying to run a marathon, it’s a stop-gap measure that can only last for a minute or two before the system crashes.

Misconceptions and Nuance

People often confuse fermentation with anaerobic respiration. Technically, in the strictly biological sense, they aren't the exact same thing, though they both happen without oxygen. True anaerobic respiration still uses an electron transport chain; fermentation doesn't. Fermentation is even lazier—it just dumps electrons onto an organic molecule and calls it a day.

Also, don't believe the myth that anaerobic exercise doesn't burn fat. While the process of anaerobic respiration uses glucose (sugar) exclusively, the high-intensity nature of anaerobic workouts spikes your metabolic rate for hours afterward, leading to what’s known as EPOC (Excess Post-exercise Oxygen Consumption). You're basically paying back the "oxygen debt" you incurred during the sprint.

Evolution’s Greatest Workaround

If you look back 2.5 billion years, the Earth didn't have an oxygen-rich atmosphere. Everything was anaerobic. When the "Great Oxidation Event" happened, it was a mass extinction for many anaerobic organisms. The survivors retreated to the mud, the deep ocean, and eventually, the guts of animals.

👉 See also: Why Doing Leg Lifts on a Pull Up Bar is Harder Than You Think

Your own digestive tract is a massive anaerobic bioreactor. The bacteria in your colon help you break down complex fibers that your human enzymes can't touch. They do this through fermentation, producing short-chain fatty acids that actually nourish your gut lining. You are, in a very real sense, a walking colony that depends on anaerobic life to stay healthy.

Practical Implications for Health and Fitness

Understanding how to define anaerobic respiration in biology isn't just for passing a test. It changes how you train.

- Threshold Training: If you want to get faster, you have to raise your "lactate threshold." This is the point where your body shifts from aerobic to anaerobic. By training right at this edge, you teach your body to clear lactic acid more efficiently.

- Explosive Power: Weightlifting and sprinting are almost entirely anaerobic. You are building the machinery to generate massive force in seconds without waiting for your lungs to catch up.

- Metabolic Flexibility: Switching between these two systems efficiently is a hallmark of metabolic health. People who are "metabolically stiff" struggle to switch to anaerobic power, leading to quicker fatigue.

What to Do Next

If you’re looking to apply this knowledge, start by experimenting with Interval Training (HIIT). This forces your body to cycle between aerobic and anaerobic states. You'll feel the burn (anaerobic), then recover (aerobic).

Watch your recovery times. If it takes you five minutes to catch your breath after a thirty-second sprint, your aerobic system isn't strong enough to "pay back" the debt created by your anaerobic system. Focus on zone 2 cardio (light jogging where you can still talk) to build the aerobic base that supports your anaerobic peaks.

Biology isn't just something in a textbook; it's the reason your muscles ache, the reason your bread tastes good, and the reason life exists in the darkest corners of the planet.

Actionable Steps:

- Test your threshold: Find a hill and sprint up it for 30 seconds. Note how long it takes for your heart rate to return to a resting state; this is a direct measure of your metabolic recovery efficiency.

- Diversify your gut: Eat fermented foods like kimchi or kefir. These are products of anaerobic respiration that introduce beneficial bacteria into your "internal anaerobic chamber."

- Audit your workouts: Ensure you aren't just staying in the "easy" aerobic zone. Pushing into the anaerobic zone twice a week triggers hormonal responses, like growth hormone release, that steady-state cardio simply can't match.