You’ve probably seen them in a high school biology textbook. They look like a spilled blot of ink or a discarded piece of chewed gum. But honestly, the standard amoeba definition most of us carry around is a bit too simple. We tend to think of "an amoeba" as a specific animal, like a tiger or a goldfish. It isn't.

It's actually a shape. Or rather, a way of being.

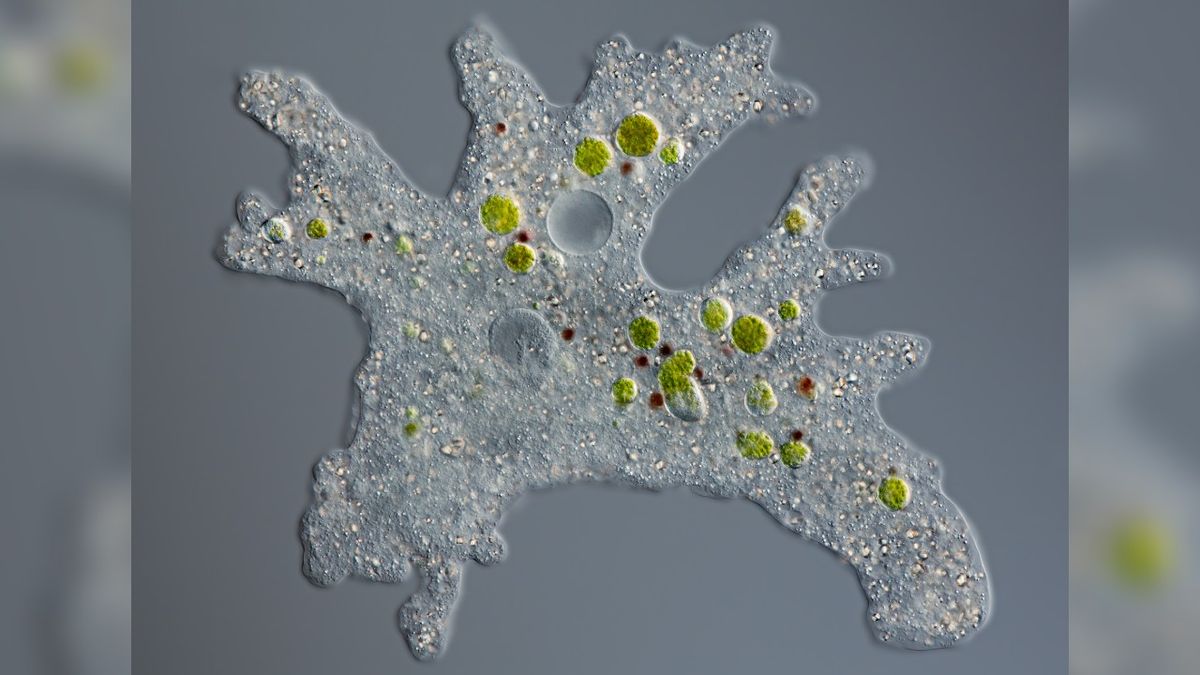

Biologists use the term "amoeboid" to describe any cell that moves by crawling. They stretch out parts of their body—called pseudopodia or "false feet"—and just sort of flow into them. It's messy. It’s slow. But for a single-celled organism, it is an incredibly effective way to hunt. Imagine if you could turn your arm into a liquid, stretch it around a pizza, and then just absorb that pizza directly through your skin. That’s the daily life of an amoeba.

Beyond the Textbook: What Is an Amoeba, Really?

If we want to get technical, the amoeba definition refers to a type of cell or unicellular organism which has the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and retracting pseudopods. They don't have a fixed mouth. They don't have a nervous system. They don't have a skeleton. Yet, they manage to navigate complex environments with surprising precision.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your Pages to PDF Converter Always Messes Up Your Layout (and How to Fix It)

Most people are thinking of Amoeba proteus when they use the word. This is the "classic" version found in freshwater ponds, crawling over rotting leaves. It’s huge for a single cell. You can actually see it with the naked eye if the light hits it just right—it looks like a tiny, moving speck of white dust. But the world of amoeboid protozoa is way bigger than just one species. It includes everything from the giant Pelomyxa, which can have hundreds of nuclei, to the tiny, shelled testate amoebae that build literal houses out of sand grains.

Nature is weird.

The Mechanics of Squishing Around

How does something without muscles move? It’s all about the cytoplasm. Inside the cell, the fluid comes in two flavors: the watery endoplasm in the middle and the stiffer, gel-like ectoplasm near the edges.

When an amoeba wants to move, it chemically triggers a shift. The "gel" becomes "sol" (liquid), and the internal pressure pushes that liquid forward. Then, it solidifies again to anchor the cell. This constant shifting between liquid and solid states is basically biological hydraulics. It’s a sophisticated dance of proteins like actin and myosin—the same stuff in your own muscles, just organized differently.

Eating by Enveloping

When an amoeba finds a tasty bacterium or a smaller protist, it doesn't just bite it. It surrounds it. This process is called phagocytosis. The pseudopods reach out like arms, encircle the prey, and fuse together. The prey is now trapped in a bubble called a food vacuole.

Then comes the grim part.

The amoeba pumps digestive enzymes into that bubble. The prey is dissolved alive, and the nutrients are absorbed directly into the cytoplasm. Anything left over—the "trash"—is simply left behind as the amoeba crawls away. It’s efficient. It’s brutal. It’s been working for billions of years.

Why the Amoeba Definition is Getting Complicated

Taxonomy is a headache. Back in the day, everything was either a plant or an animal. Amoebae were tossed into a junk drawer kingdom called Protista. But modern genetics has blown that wide open. We now know that "amoebae" are scattered all across the tree of life.

Some are closely related to fungi. Others are closer to green algae. There are even amoeboid cells inside your own body. Your white blood cells—specifically macrophages—are essentially amoebae that live in your blood. They crawl through your tissues, stretching out pseudopods to grab and eat invading bacteria. You are literally kept alive by a fleet of internal amoebae.

The Famous "Brain-Eater"

We can't talk about these things without mentioning Naegleria fowleri. It’s the headline-grabbing "brain-eating amoeba." While it fits the amoeba definition because of how it moves, it’s actually a facultative parasite. Usually, it’s perfectly happy eating bacteria in warm lake water. The problem starts when it gets sniffed up a human nose. It follows the olfactory nerve straight to the brain. It’s rare, but it’s a reminder that these "simple" organisms can be incredibly dangerous under the right circumstances.

Where They Live and Why They Matter

Amoebae are everywhere. If there is moisture, there is likely an amoeba.

📖 Related: Why Pictures of Earth From Moon Still Change Everything We Know

- Freshwater: Ponds, lakes, and even the film of water on a damp leaf.

- Saltwater: Oceans are teeming with them, including the stunning radiolarians with their glass-like skeletons.

- Soil: They play a massive role in the nitrogen cycle by eating bacteria and pooping out nutrients that plants need.

- Inside Hosts: Many are harmless hitchhikers in our guts (Entamoeba coli), while others cause dysentery (Entamoeba histolytica).

Without them, the world’s ecosystems would likely stall out. They are the great recyclers of the microbial world. They keep bacterial populations in check. They provide food for slightly larger microscopic creatures like rotifers and copepods.

Common Misconceptions to Clear Up

One big mistake people make is thinking amoebae are "primitive." That word is a trap. Just because they are single-celled doesn't mean they are simple. An amoeba has to do everything a human does—find food, avoid predators, maintain homeostasis, reproduce—all within the confines of one single cell membrane.

They also aren't immortal. While they reproduce by binary fission (splitting in two), they can be killed by heat, dehydration, or lack of food. However, many species have a "cheat code" for survival: encystment. When things get bad, the amoeba pulls itself into a ball, loses most of its water, and secretes a hard, protective shell. It can stay in this dormant state for years, blowing around in the wind, waiting for a drop of water to wake it up.

Future Tech and the Amoeba

Interestingly, engineers are looking at the amoeba definition to design better robots. "Soft robotics" is a field that tries to mimic the fluid, non-rigid movement of these organisms. Imagine a robot that can squeeze through a crack in a collapsed building to find survivors. It wouldn't have gears or joints; it would move like a liquid.

We’re also using them in computing. The "amoeba-inspired" computer uses the physical growth patterns of the slime mold Physarum polycephalum (which has an amoeboid stage) to solve complex routing problems. It turns out that a brainless blob is actually better at finding the shortest path between two points than many human-designed algorithms.

📖 Related: How to Add a Bookmark on iPad: What Most People Get Wrong

Taking Action: How to Observe Them

If you want to see an amoeba yourself, you don't need a million-dollar lab. A basic compound microscope will do.

Go to a local pond. Look for some submerged lily pads or decaying sticks. Scrape a bit of the "slime" (the biofilm) into a jar with some pond water. Back at home, put a single drop on a slide. Don't use a coverslip yet; give it a minute to settle.

Look for something that isn't swimming fast. Look for a slow, creeping "ooze." Once you find one, watch it for ten minutes. You'll see the pseudopods extend. You'll see the internal organelles—the nucleus, the contractile vacuole pumping out water, the dark spots of digesting food—tumble around inside. It’s a window into a version of life that is radically different from our own, yet fundamentally tied to the same biological rules.

Respect the blob. It’s been here longer than we have, and it’ll likely be here long after we’re gone.