You’ve probably smelled an amine group before, even if you didn't know the chemistry behind it. Think of the sharp, stinging scent of ammonia cleaner. Or, if we’re being honest, the unmistakable stench of rotting fish. That’s the work of trimethylamine. While they might offend your nose, these nitrogen-based structures are basically the building blocks of your entire existence. Without them, your DNA wouldn't hold together, and the protein in your muscles wouldn't exist. It’s a weird paradox. The same chemical family that makes a dumpster smell bad is also responsible for the "happy" chemicals in your brain, like serotonin and dopamine.

What Exactly Is an Amine Group?

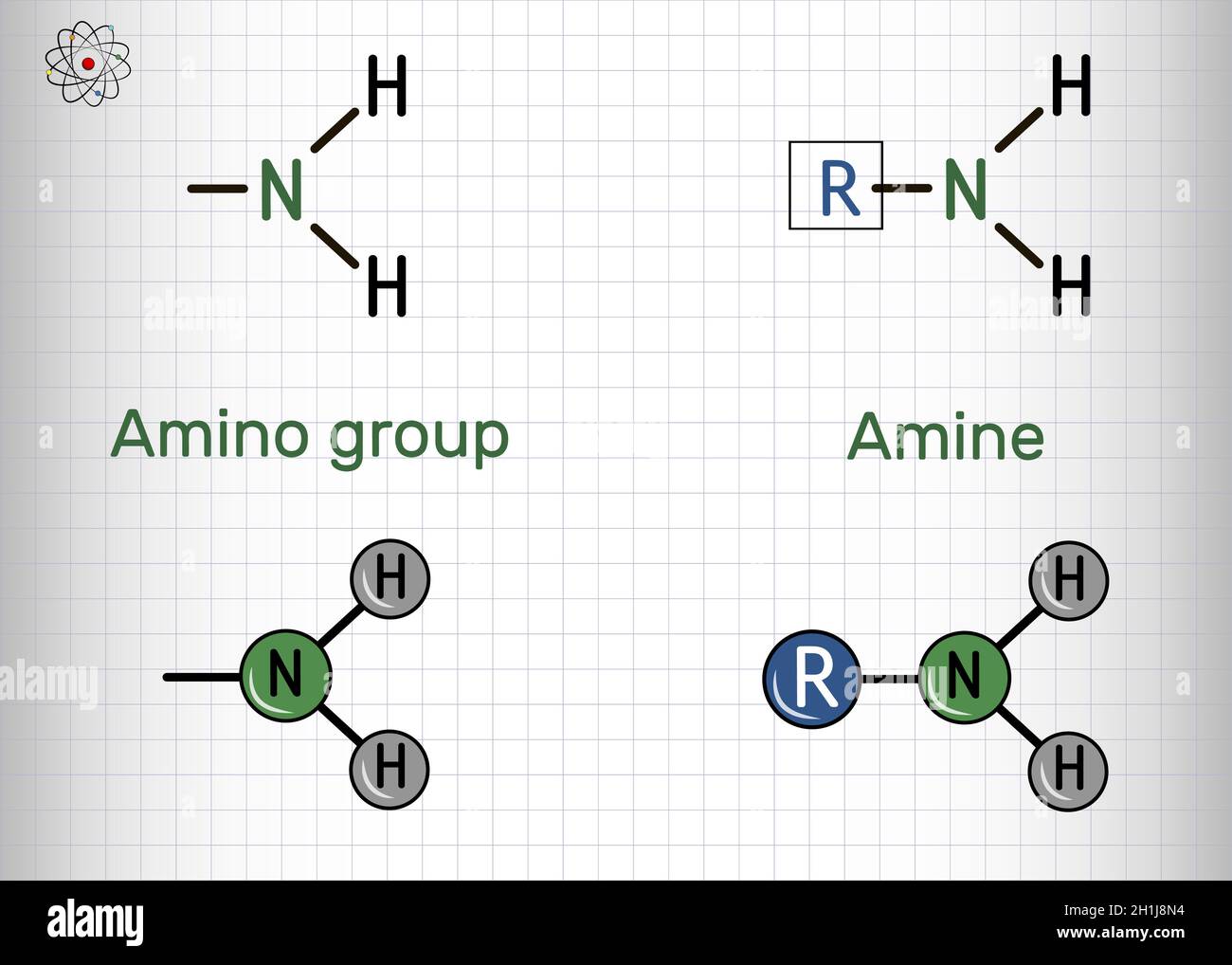

At its simplest, an amine group is a nitrogen atom bonded to some combination of hydrogen atoms and carbon groups. Chemically, we view them as derivatives of ammonia ($NH_3$). If you swap out one or more of those hydrogen atoms for a carbon-based chain (an alkyl or aryl group), you’ve got an amine.

Nitrogen is the star of the show here. Because nitrogen has a lone pair of electrons, it’s "electron-rich." This makes the amine group basic and nucleophilic. In plain English? It’s looking to react. It wants to share those electrons with something else. This reactivity is why amines are so prevalent in the pharmaceutical industry. If you look at the back of a pill bottle, there is a massive chance that the active ingredient contains at least one nitrogen atom tucked away in an amine structure.

The Hierarchy of Amines

We don't just lump them all together. Chemists categorize them based on how many carbon "friends" the nitrogen has.

A primary amine has one carbon group attached ($R-NH_2$). Methylamine is a classic example—yes, the one made famous by Breaking Bad, though in reality, it's a colorless gas used in everything from pesticides to photographic developers. Then you have secondary amines, where the nitrogen is sandwiched between two carbons ($R_2NH$). Finally, tertiary amines have three carbon attachments ($R_3N$), leaving no hydrogens directly bonded to the nitrogen.

There is also something called a quaternary ammonium cation. In this case, the nitrogen is bonded to four groups, giving it a permanent positive charge. You’ll find these in your fabric softeners and disinfectants because that positive charge likes to cling to surfaces.

📖 Related: Why the CH 46E Sea Knight Helicopter Refused to Quit

Why Biology Obsesses Over Nitrogen

If you stripped the amine groups out of your body, you would effectively dissolve. Amino acids are the most famous "customers" of this functional group. Every single amino acid—the stuff that builds your hair, skin, and enzymes—contains both a carboxylic acid group and an amine group.

When these acids chain together, they form peptide bonds. It’s a sophisticated Lego set. The nitrogen in the amine group of one amino acid links to the carbon of another. This creates the primary structure of proteins.

But it goes deeper than just muscle tissue. Let’s talk about neurotransmitters. Most of the chemicals that dictate your mood—epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine, and the aforementioned serotonin—are amines. They are often called "biogenic amines." When a doctor prescribes an antidepressant like an SSRI, they are essentially messing with the way your brain handles these amine-containing molecules.

The Industrial and "Real World" Side

It isn't all just biology and brain chemistry. We use these things everywhere.

- Dyes: The fashion industry loves amines. Aniline is a primary aromatic amine used to create those incredibly vibrant synthetic dyes that don't wash out of your jeans after one cycle.

- Water Treatment: Certain amines help remove carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide from natural gas. It’s a process called "sweetening."

- Medicine: Morphine, codeine, and even synthetic painkillers like lidocaine are alkaloids, which are naturally occurring amines found in plants.

Actually, here is a fun (and gross) fact. When living tissue dies, enzymes start breaking down proteins. This releases two specific amines: putrescine and cadaverine. The names aren't subtle. They are responsible for the "smell of death." It’s nature’s way of telling scavengers that dinner is served and telling humans to stay far, far away.

👉 See also: What Does Geodesic Mean? The Math Behind Straight Lines on a Curvy Planet

Solving the Solubility Problem

One of the coolest things about an amine group is its ability to form hydrogen bonds. Because nitrogen is more electronegative than hydrogen, the $N-H$ bond is polar. This makes smaller amines very soluble in water.

However, as the carbon chain gets longer, the molecule becomes "greasy" and stops dissolving well. In the world of medicine, this is a huge hurdle. Many drugs are amines that don't dissolve in the bloodstream easily. To fix this, chemists turn them into "amine salts" by reacting them with an acid like hydrochloric acid. If you see "HCl" at the end of a drug name on a label—like Sertraline HCl—that’s exactly what happened. They turned the amine into a salt to make it easier for your body to absorb.

Basicity: The Amine's Secret Weapon

Why do amines behave the way they do? It comes back to that lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen. In the Brønsted-Lowry definition, an amine is a base because it can accept a proton ($H^+$).

$$R-NH_2 + H_2O \rightleftharpoons R-NH_3^+ + OH^-$$

This ability to grab a proton is what allows amines to act as buffers in biological systems. They help keep your blood pH within a very narrow, livable range. If your blood pH shifts by even a small amount, your proteins start to unfold (denature), and things go south very quickly. The amine groups on your amino acids help soak up excess acidity to prevent this.

✨ Don't miss: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

How to Identify an Amine Group in the Wild

If you’re looking at a chemical skeletal structure and you see a N poking out, you’re likely looking at an amine. But don't confuse them with amides.

An amide has a nitrogen right next to a carbonyl group (a carbon double-bonded to an oxygen). That oxygen pulls electron density away from the nitrogen, making amides much less basic and much less reactive than amines. It’s a small distinction on paper, but in the lab, they act like completely different animals. Amines are the reactive, social butterflies; amides are the stable, structural stalwarts.

Common Misconceptions

People often think "chemical" means "artificial." Amines prove that's nonsense. Your body is a massive, walking amine factory.

Another mistake? Assuming all amines are toxic. While some, like nicotine (a tertiary amine), are addictive and poisonous in high doses, others are vital nutrients. Take Vitamin B1 (thiamine). The "amine" is right there in the name "Vit-amine." Early scientists thought all vitamins were amines; they were wrong about the "all" part, but the name stuck.

Practical Steps for Chemistry Students or Hobbyists

If you are trying to master this topic for a class or just want to understand your meds better, start with these steps:

- Map the Nitrogen: Look at the structure of common drugs like Caffeine or Diphenhydramine (Benadryl). Identify if the nitrogen is primary, secondary, or tertiary.

- Check the pH: If you have a substance containing an amine, remember it will likely turn red litmus paper blue. It’s basic.

- Smell (Carefully): Familiarize yourself with the "fishy" scent of household cleaners or older seafood. That is the physical manifestation of volatile amines escaping into the air.

- Study the "Salt" Form: Look at your medicine cabinet. Count how many medications are listed as a "hydrochloride" or "sulfate" salt. You’ll see just how much we rely on amine chemistry to keep ourselves healthy.

Amines are messy, sometimes smelly, and incredibly complex. But they are the reason you can think, move, and breathe. They bridge the gap between simple inorganic nitrogen and the complex machinery of life. Next time you catch a whiff of something fishy or take a Tylenol, give a little nod to the nitrogen atom. It's doing more work than you think.