Maps are weird. We look at an america map with latitude and longitude and assume those neat little grid lines have always been there, fixed in stone like the mountains they cross. They aren't. Honestly, the dirt under your feet is moving, and the coordinate system we use to find a Starbucks or a trailhead has to keep up with a planet that refuses to stay still.

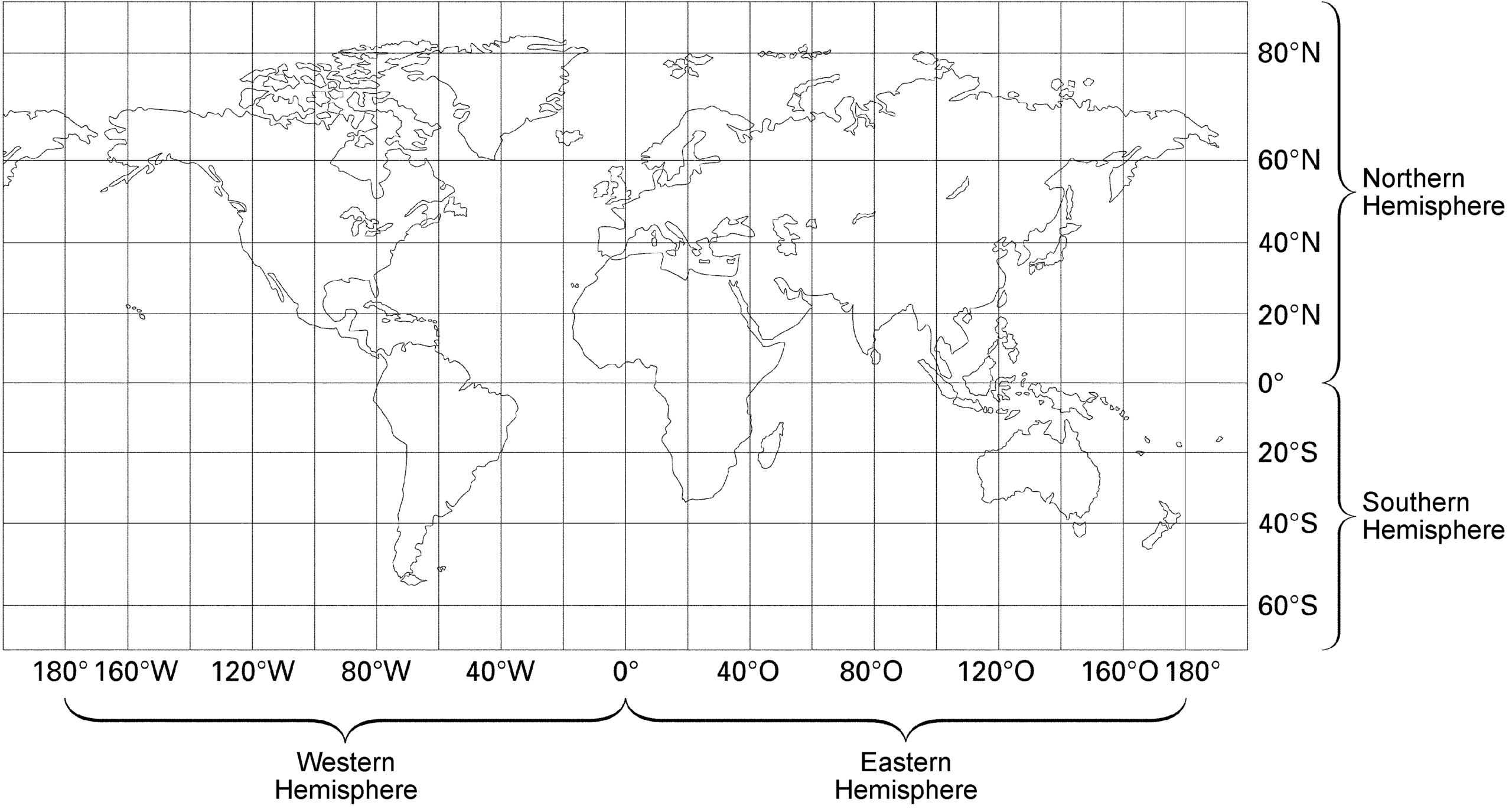

You’ve probably seen the numbers. $38^\circ N$, $97^\circ W$. That’s roughly the center of the contiguous United States, tucked away near Lebanon, Kansas. But if you’re trying to navigate the Florida Keys or the rugged coastline of Washington state, those broad strokes don't help much. Latitude and longitude are the language of the Earth, but the translation gets messy when you realize the North American Plate is drifting about an inch a year.

The Grid That Holds the States Together

Most people think a map is just a picture. It’s actually math. When you pull up an america map with latitude and longitude, you're looking at a projection—a way of flattening a sphere onto a screen or paper.

📖 Related: Why the New US Postal Service Truck Is Actually a Huge Deal

The horizontal lines are latitude. Think of them like rungs on a ladder. They measure how far north you are from the Equator. For the U.S., this starts way down in the Florida Keys at about $24^\circ N$ and stretches up to the 49th parallel, which forms that long, straight-ish border with Canada.

Then you have longitude. These are the vertical lines, the "long" ones that meet at the poles. They measure distance east or west of the Prime Meridian in Greenwich, England. America is firmly in the Western Hemisphere. Everything is "West." If you see a coordinate for New York City, it’s going to look something like $40.7128^\circ N, 74.0060^\circ W$.

The numbers feel sterile. They aren't. Behind every coordinate is a history of surveyors hacking through brush and astronomers staring at stars to figure out exactly where "here" is.

Why 49 Degrees Matters (And Why It Isn't Straight)

We talk about the "49th parallel" like it’s a perfect line. It was supposed to be. In the Treaty of 1818, the U.S. and Britain agreed that the border between U.S. territory and British North America (Canada) would follow that specific line of latitude from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains.

But 19th-century surveyors didn't have GPS. They had sextants and chains. Because of the limitations of their tech and the actual physical shape of the Earth—which isn't a perfect sphere but a lumpy "oblate spheroid"—the border zig-zags. If you look at a high-resolution america map with latitude and longitude, you'll see the "Northwest Angle." It’s a piece of Minnesota that sticks up into Canada because of a mapping error. Basically, they thought the Mississippi River started further north than it actually did.

Datums: The Invisible Foundation of Your Map

Here is something most people get wrong. They think a coordinate is absolute. It isn't. A coordinate is only as good as the "datum" it's based on.

A datum is a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape. In the U.S., we’ve used a few big ones:

- NAD27: The North American Datum of 1927. This was the gold standard for decades. It used a point in Kansas (Meades Ranch) as the "center" of everything.

- NAD83: The updated version. When satellites came along, we realized our old measurements were off by dozens of meters in some places.

- WGS84: This is what your phone uses. The World Geodetic System 1984. It’s the global standard for GPS.

If you take a coordinate from an old paper america map with latitude and longitude based on NAD27 and plug it into your modern smartphone (WGS84), you might find yourself 50 feet deep in a lake instead of on the hiking trail. This is called a "datum shift." It sounds nerdy, but for surveyors and pilots, it’s a matter of life and death.

The Problem with a Moving Target

The Earth is alive. Plate tectonics mean that North America is physically shifting. If we kept our coordinate system fixed to the stars, the physical landmarks on the ground—like the Washington Monument—would have different coordinates every year.

👉 See also: Por qué tus fondos de portada para facebook se ven tan mal (y cómo arreglarlo hoy mismo)

To solve this, we use "static" datums that move with the plate. But as we move into 2026 and beyond, the National Geodetic Survey (NGS) is replacing NAD83 with a new, even more precise system called the North American Terrestrial Reference Frame (NATRF2022). They're doing this because GPS has become so precise that the old errors are finally becoming annoying. We’re talking about centimeter-level accuracy now.

Reading the Map: From Maine to California

Let's look at the extremes. It helps put the scale of the country in perspective.

Maine is often thought of as the "most north," but that’s not quite right if you include the whole map. Angle Inlet, Minnesota, is the northernmost point of the lower 48 states at roughly $49.38^\circ N$. Of course, if you zoom out to a full america map with latitude and longitude that includes Alaska, everything changes. Point Barrow, Alaska, sits at a staggering $71.3^\circ N$. That’s well above the Arctic Circle.

On the flip side, the southernmost point of the 50 states is Ka Lae, Hawaii ($18.9^\circ N$). In the contiguous U.S., it’s Ballast Key, Florida ($24.5^\circ N$).

Longitude is just as expansive.

- East Coast: West Quoddy Head, Maine, is the easternmost point at $66.9^\circ W$.

- West Coast: Cape Alava, Washington, sits at $124.7^\circ W$ (contiguous).

- The Alaska Factor: Here is a fun trivia fact. Because the Aleutian Islands cross the 180th meridian, parts of Alaska are technically in the Eastern Hemisphere. This means Alaska is the northernmost, westernmost, and easternmost state in the country. Sorta breaks your brain, right?

How to Actually Use This Information

Most of us just want to find a cool spot on Google Maps. But understanding coordinates opens up a whole different layer of the world.

📖 Related: Elon Musk's xAI Startup Raises Another $6bn: What Most People Get Wrong

If you’re looking at a digital america map with latitude and longitude, you'll likely see coordinates in one of two formats:

- Decimal Degrees (DD): $34.0522, -118.2437$ (Typical for Google Maps).

- Degrees, Minutes, Seconds (DMS): $34^\circ 03' 08" N, 118^\circ 14' 37" W$ (The traditional way).

Converting between them is just basic math. There are 60 minutes in a degree and 60 seconds in a minute. If you’re out hiking and your GPS gives you decimals but your paper map uses DMS, you just multiply the decimal part by 60 to get your minutes. Easy.

Modern Tools for the Modern Map

We don't carry sextants anymore. We carry supercomputers in our pockets. But those computers rely on a massive infrastructure of ground stations.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) operates the Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS). It’s a network of ground-based stations that correct GPS signals. Without these corrections, your america map with latitude and longitude might be off by 10 meters. With them, it’s accurate to within a few feet. This is how planes land in fog and how your Uber driver knows exactly which side of the street you’re standing on.

The Cultural Map

The lines we draw on the Earth aren't just for navigation. They define who we are. The Mason-Dixon Line, perhaps the most famous line in American history, is essentially a survey of a specific latitude ($39^\circ 43' N$). It was meant to settle a property dispute between Pennsylvania and Maryland. It ended up defining the cultural divide between the North and the South for over a century.

Then there is the 100th Meridian. Geographically, it’s just $100^\circ W$ longitude. But ecologically, it’s the "aridity line." West of this line, the climate gets significantly drier. It’s the edge of the Great Plains. It dictates where we grow wheat, where we need irrigation, and where the "Old West" truly begins. When you look at an america map with latitude and longitude, you aren't just looking at coordinates; you're looking at the blueprint for American agriculture and expansion.

Mapping Your Own Path

If you want to master the map, stop just looking at the blue dot on your phone. Start noticing the numbers.

Actionable Next Steps

- Check Your Settings: Open your favorite map app and switch the coordinate display to Decimal Degrees. It’s the lingua franca of modern mapping.

- Find Your "Home" Coordinate: Learn the specific latitude and longitude of your house. It’s a great way to understand your place in the global grid.

- Explore the NGS Data Explorer: If you want to see the "real" map, go to the National Geodetic Survey website. You can find actual survey markers (brass discs) near you. They are the physical anchors for every america map with latitude and longitude ever made.

- Download Offline Maps: GPS works via satellite, but the "map" part of your phone requires data. If you’re heading into the wilderness, download the topographical maps for your specific coordinates beforehand.

Maps are a mix of high-tech satellite data and old-school grit. The next time you see those grid lines, remember that they are a human attempt to make sense of a massive, shifting, beautiful piece of rock.