You’ve probably heard that Leonardo da Vinci was a procrastinator. It’s the go-to fun fact for people who want to feel better about their own unfinished projects. But honestly? Calling him a procrastinator is like calling a hurricane "a bit windy."

He was a perfectionist obsessed with the physics of light, the anatomy of a smile, and the way water swirls around a rock. That obsession is why, depending on which art historian you ask, there are only about 15 to 20 surviving works that we can confidently call all of Leonardo da Vinci paintings.

Think about that. One of the most famous humans to ever live left behind fewer finished paintings than most hobbyists produce in a year.

The "Complete" List (It’s Complicated)

If you're looking for a neat, numbered list, you won't find one here because the art world doesn't work like that. Attributions change. Science gets better.

Basically, there's a "core" group of paintings everyone agrees on, and then there's a "maybe" pile that keeps scholars up at night.

The Early Days in Verrocchio’s Shop

Leonardo didn't just pop out of the womb painting masterpieces. He was an apprentice.

- The Baptism of Christ (c. 1475): This was a team effort. His teacher, Verrocchio, did the heavy lifting, but Leonardo painted the angel on the left. Legend says Verrocchio saw how much better his student was and swore he’d never paint again. Kinda dramatic, but that’s the Renaissance for you.

- The Annunciation (1472–1475): This is one of his first big solo projects. If you look closely at the Virgin Mary’s arm, the perspective is actually a bit wonky. Even geniuses have "Day 1" struggles.

- Ginevra de' Benci (c. 1474–1478): This is the only Leonardo painting you can see in the Americas (it’s in D.C.). It’s a portrait of a teenage girl who looks like she’s already tired of everyone’s nonsense.

The Milan Years and the Big Hits

When Leonardo moved to Milan, he started leaning into his "polymath" energy. He wasn't just a painter; he was a weapons designer, a party planner, and a mapmaker.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

- The Virgin of the Rocks (c. 1483–1486): There are actually two versions of this. One is in Paris, and the other is in London. Why? Because of a legal dispute over money, naturally.

- Lady with an Ermine (c. 1489–1491): This is arguably better than the Mona Lisa. It’s Cecilia Gallerani, the mistress of the Duke of Milan. The way she’s turning her head was revolutionary for the time. It feels like she’s actually reacting to someone walking into the room.

- The Last Supper (1495–1498): This isn't a fresco. Leonardo hated how fast fresco paint dried, so he experimented with a mix of oil and tempera on dry plaster. It was a disaster. The painting started peeling off the wall almost immediately. What you see today in Milan is about 20% Leonardo and 80% restoration work.

What Happened to the Lost Masterpieces?

We talk about all of Leonardo da Vinci paintings like we have the whole set, but we’re missing some of the best ones.

The Battle of Anghiari

This was supposed to be his greatest work. A massive mural in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. Leonardo tried another weird experimental technique involving heat and wax. The wax melted, the paint ran, and he just... walked away.

For centuries, people have thought the original might still be hidden behind a false wall built by Giorgio Vasari. In 2012, researchers even drilled tiny holes and found black pigment similar to the Mona Lisa’s. But then the project got shut down. It's the ultimate art history cliffhanger.

Leda and the Swan

Leonardo definitely painted this. We have his sketches. We have copies made by his students. But the original? Gone. It probably belonged to the French Royal collection before it vanished in the 1600s.

The $450 Million Headache: Salvator Mundi

You can’t talk about his catalog without mentioning the Salvator Mundi. It’s the most expensive painting ever sold, and it might not even be fully by Leonardo.

Some experts, like Matthew Landrus from Oxford, think it’s mostly the work of his assistant, Bernardino Luini. They argue Leonardo maybe did 5% to 20% of it—the "finishing touches." Others, like Martin Kemp, are certain it’s a real Leonardo.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

The painting has "pentimenti"—which is a fancy way of saying the artist changed their mind. You can see two thumbs on Christ’s right hand under the X-ray. Usually, that’s a sign of an original work, not a copy. But after it sold for $450 million in 2017, it disappeared from the public eye. It's reportedly sitting on a yacht or in a high-security vault in Switzerland.

How to Tell a Leonardo from a Fake

Leonardo had a "vibe" that was almost impossible to copy perfectly. He used a technique called sfumato.

Basically, he didn't use lines. If you look at the corner of the Mona Lisa’s mouth, there’s no hard border. It just dissolves into shadow. He realized that in real life, there are no outlines. Everything is just light hitting surfaces.

He also obsessed over optics. In the Virgin of the Rocks, the way light filters through the water and the cave shouldn't have been possible to paint in the 1480s. He was literally studying the way the human eye perceives depth while he was supposed to be finishing commissions.

The Final Works

Toward the end of his life, Leonardo became even more selective.

- The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (c. 1503–1519): He worked on this for nearly 20 years. He never actually finished it.

- Mona Lisa (c. 1503–1519): Contrary to popular belief, he didn't just paint this and hand it over. He carried it with him everywhere, from Italy to France, constantly adding microscopic layers of glaze.

- Saint John the Baptist (c. 1513–1516): His last major painting. It’s dark, weird, and a little bit unsettling. It’s the work of a man who spent his whole life trying to paint the invisible.

Seeing Them for Yourself

If you want to see the "real" Leonardo, don't just look at a poster. You have to go to the source.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

- The Louvre, Paris: Holds the biggest collection, including the Mona Lisa and The Virgin of the Rocks.

- The Uffizi, Florence: Great for his early work like The Annunciation.

- The National Gallery, London: Home to the second Virgin of the Rocks and the breathtaking Burlington House Cartoon.

Next time you’re looking at a list of all of Leonardo da Vinci paintings, remember that the list is always growing or shrinking. New tech might prove a "fake" is real tomorrow. Or it might prove the masterpiece we love was actually painted by a guy named Boltraffio.

That’s the beauty of it. Leonardo left us with a puzzle that we’re still trying to solve 500 years later.

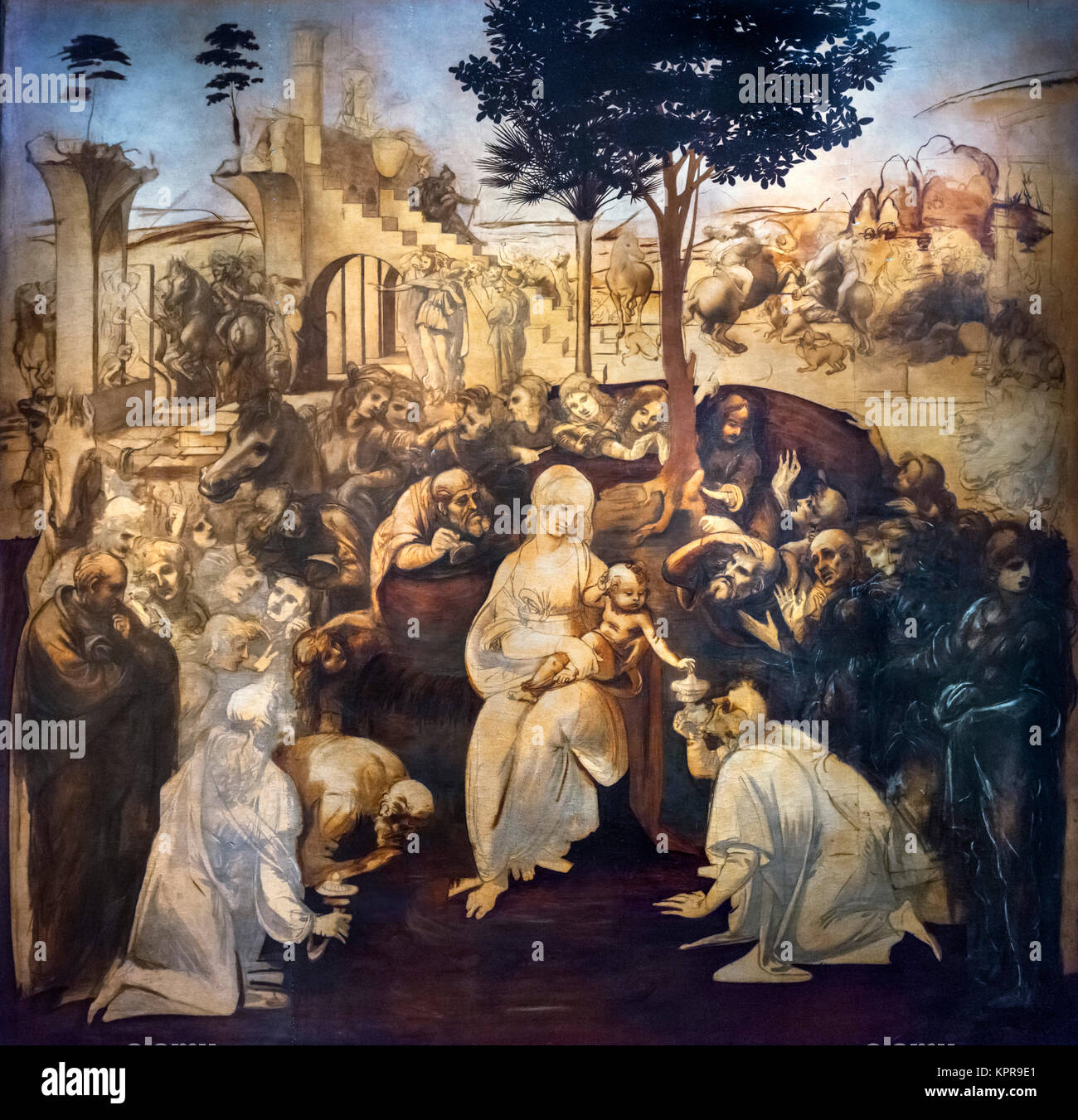

To truly understand his work, start by looking at his drawings and notebooks alongside the paintings. The sketches for the Adoration of the Magi show the chaotic math behind his compositions. Seeing the "skeleton" of his ideas makes the finished (or unfinished) paintings feel much more human.

Check the digital archives of the Codex Arundel or visit a major museum’s "Leonardo" wing to see how he used light to define shape without lines.

[/article]