You probably think you know the Alice in Wonderland book Lewis Carroll wrote because you've seen the Disney movie. Or maybe the Tim Burton one with the heavy CGI. Honestly? Those versions are basically "Alice-lite." They take the trippy visuals but strip out the weird, gritty, math-obsessed logic that actually makes the book a masterpiece.

Carroll wasn't just some guy writing a bedtime story for a kid named Alice Liddell. He was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a high-level mathematician at Oxford who was arguably a bit of a grump about how modern math was changing in the mid-1800s. When you read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, you aren't just reading a fairy tale. You’re reading a massive, satirical middle finger to the Victorian education system and the "new" math of the 19th century.

It's weird. It's jarring. And it's way more intellectual than the cartoons let on.

The Real Story Behind the "Golden Afternoon"

The legend goes that on July 4, 1862, Dodgson and his friend Reverend Robinson Duckworth took the three Liddell sisters—Lorina, Alice, and Edith—on a rowing trip up the River Thames. To keep them from getting bored, he spun this wild yarn about a girl falling down a rabbit hole.

Alice Liddell loved it. She begged him to write it down.

But here’s the thing: historians have looked at the weather reports from that day. It was actually "cool and rather wet." So that "golden afternoon" Carroll described in the book's introductory poem? Likely a bit of a romanticized memory. It took him two years to actually finish the manuscript, which he originally titled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. He even drew the illustrations himself, though they look way creepier than the famous John Tenniel ones we use today.

Why the Alice in Wonderland Book Lewis Carroll Wrote is Actually About Math

If you hated algebra in high school, you might actually relate to Alice more than you think.

Dodgson was a conservative mathematician. He liked Euclid. He liked logic that stayed in its lane. At the time, math was becoming more abstract—people were starting to play with imaginary numbers and non-Euclidean geometry. Dodgson thought this was absolute nonsense.

Take the Mad Hatter’s tea party. It’s not just a bunch of characters being "wacky." Some scholars, like Melanie Bayley from Oxford University, argue the scene is a direct jab at William Rowan Hamilton’s work on quaternions.

🔗 Read more: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Quaternions involve four dimensions.

When the fourth dimension (Time) leaves the party, the characters are stuck rotating around a table in three dimensions forever. "It’s always tea-time," the Hatter says. They’re stuck in a loop because the math doesn't work without the missing variable.

Then there’s the Caterpillar.

He’s sitting there smoking a hookah, telling Alice that changing size is perfectly normal. This reflects the "symbolic algebra" emerging at the time, where the actual value of things didn't matter as much as the internal logic of the equation. Alice is terrified because her "size" (her value) keeps changing, and she feels like she's losing her identity.

- Alice tries to multiply.

- She says, "Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear!"

- People think she’s just being silly.

- Actually, if you use a base-18 number system, 4 x 5 is 12.

- If you use base-21, 4 x 6 is 13.

Carroll was literally hiding base-shifting math problems in a kids' book. It’s brilliant. It’s also slightly unhinged.

The Victorian Satire You Probably Missed

The 1860s were a stiff time. Kids were expected to be seen and not heard, and they had to memorize these incredibly boring, moralistic poems. Carroll hated that.

Throughout the book, Alice tries to recite poems she’s learned in school, like "Against Idleness and Mischief" by Isaac Watts. But in Wonderland, the words come out wrong. Instead of a poem about a busy bee being a good little worker, it becomes a poem about a crocodile eating little fish with "gently smiling jaws."

He was parodying the "correct" way to raise a child. Wonderland is a place where every authority figure—the Duchess, the Queen of Hearts, the Gryphon—is either completely incompetent, violent, or insane. For a Victorian child, reading a book where adults were the ones who didn't make sense was revolutionary. It was punk rock for the 1860s.

💡 You might also like: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

The Controversy: Was Dodgson... Weird?

We have to address the elephant in the room. There’s been a lot of modern speculation about Dodgson’s relationship with Alice Liddell. Some biographers have pointed to his "child-friendships" and his photography as evidence of something untoward.

However, many historians, like Karoline Leach, argue that our modern lens is distorting the reality. In the Victorian era, "child-friendships" were a recognized, albeit slightly sentimental, social thing. Most of his "muses" were actually young women in their late teens or early twenties, but the "Alice" myth has overshadowed that.

The Liddell family did eventually have a "falling out" with Dodgson, and several pages from his diaries were cut out by his descendants after his death. We will never know what those pages said. It could have been a marriage proposal to Alice (who was 11 at the time, which was young even then), or it could have been a dispute with the girls' governess. The mystery is part of the book's dark allure.

It Wasn't an Immediate Smash Hit

We think of it as a timeless classic, but the first print run of the Alice in Wonderland book Lewis Carroll produced was actually a disaster.

Dodgson was a perfectionist. He hated the way the 2,000 copies were printed—he thought the illustrations looked muddy. He recalled the entire batch and forced the publisher to redo them. Those original "1865 Alices" are now some of the most valuable books in the world. Only about 22 are known to exist. If you find one in your attic, you’re looking at a $2 million to $3 million payday.

Once the "perfected" version hit the shelves in late 1865 (dated 1866), it took off. Even Queen Victoria was supposedly a fan. Legend says she asked Dodgson to send her his next book, expecting more talking rabbits, and he sent her An Elementary Treatise on Determinants.

He later denied this happened, but it’s a great story.

The Language and the "Rabbit Hole"

Carroll changed how we speak. He invented words. He popularized "chortle" and "galumph" in the sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, but the first book gave us the concept of the "rabbit hole."

📖 Related: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

Think about that. Every time someone on the internet talks about going down a "rabbit hole" of conspiracy theories or weird Wikipedia pages, they are referencing Charles Dodgson’s math-driven satire.

The Cheshire Cat’s grin, the Mad Hatter, being "off with their heads"—these aren't just tropes. They are symbols of a world where logic is applied so strictly that it becomes absurd. The Queen of Hearts isn't just a villain; she’s the embodiment of "Trial by Decree" rather than "Trial by Jury."

Key Characters and Their Reality

- The White Rabbit: He represents the frantic, time-obsessed nature of adult life. He’s the only character who seems to have a "job," and he’s terrified of being late for it.

- The Cheshire Cat: He’s the only one who realizes everyone is mad. He’s essentially the narrator’s voice inside the story.

- The Duchess: A parody of the Victorian socialite who tries to find a "moral" in everything, even when the moral makes zero sense.

How to Read Alice Today

If you’re going to pick up the Alice in Wonderland book Lewis Carroll wrote, don't read it as a story for five-year-olds. Read it as a surrealist critique of how we think.

- Look for the puns. Most are based on 19th-century British slang that we’ve forgotten.

- Pay attention to the shifts in scale. Alice growing and shrinking isn't just "magic"—it's a metaphor for the awkwardness of puberty and the feeling of not fitting into the adult world.

- Check the footnotes. If you can, get The Annotated Alice by Martin Gardner. It explains all the math and the hidden jokes about Oxford faculty members that would otherwise go right over your head.

The book is short. You can finish it in an afternoon. But you’ll probably spend the next week wondering if your own life makes as little sense as the Mad Hatter’s tea party.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Read

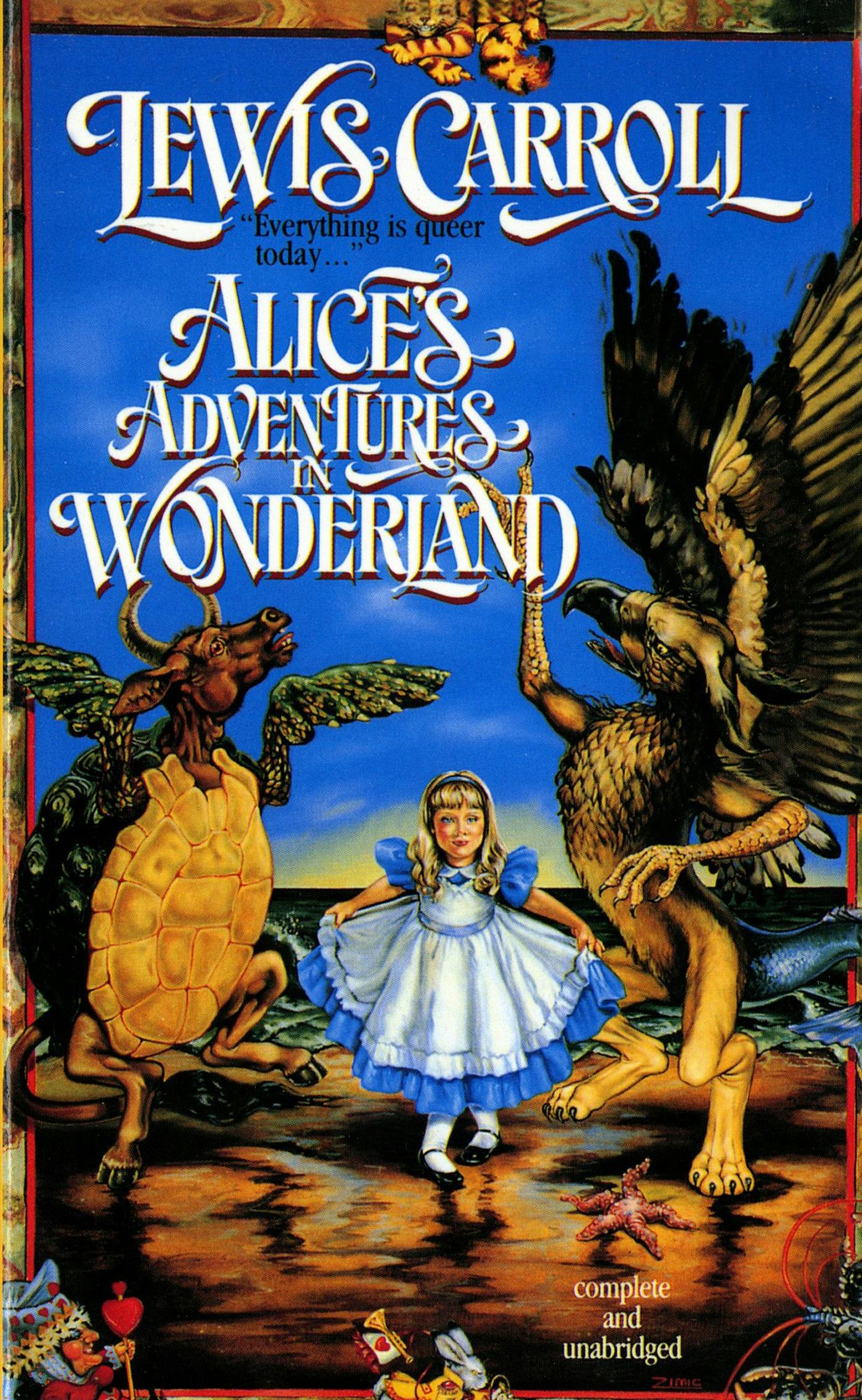

If you want to truly appreciate the work, skip the simplified editions. Find a version that includes the original John Tenniel woodblock engravings; the art is inseparable from the text.

Try reading a chapter out loud. Carroll wrote this to be heard. The rhythm of the nonsense poems—like "The Lobster Quadrille"—only really clicks when you hear the meter.

Finally, compare it to the sequel, Through the Looking-Glass. While the first book is based on the fluid, chaotic logic of a dream (and playing cards), the second is based on the rigid, calculated moves of a chess game. Seeing how Carroll moves from the "randomness" of Wonderland to the "destiny" of the looking-glass world gives you a much better handle on why he remains one of the most complex figures in English literature.

Don't just watch the movies. They miss the point. The book is where the real madness is.

Get a copy of the Annotated Alice to see the math diagrams. Read the "Jabberwocky" poem in the sequel immediately after finishing the first book. Research the "Oxford Movement" to understand the religious tension Carroll was navigating while writing about talking animals.