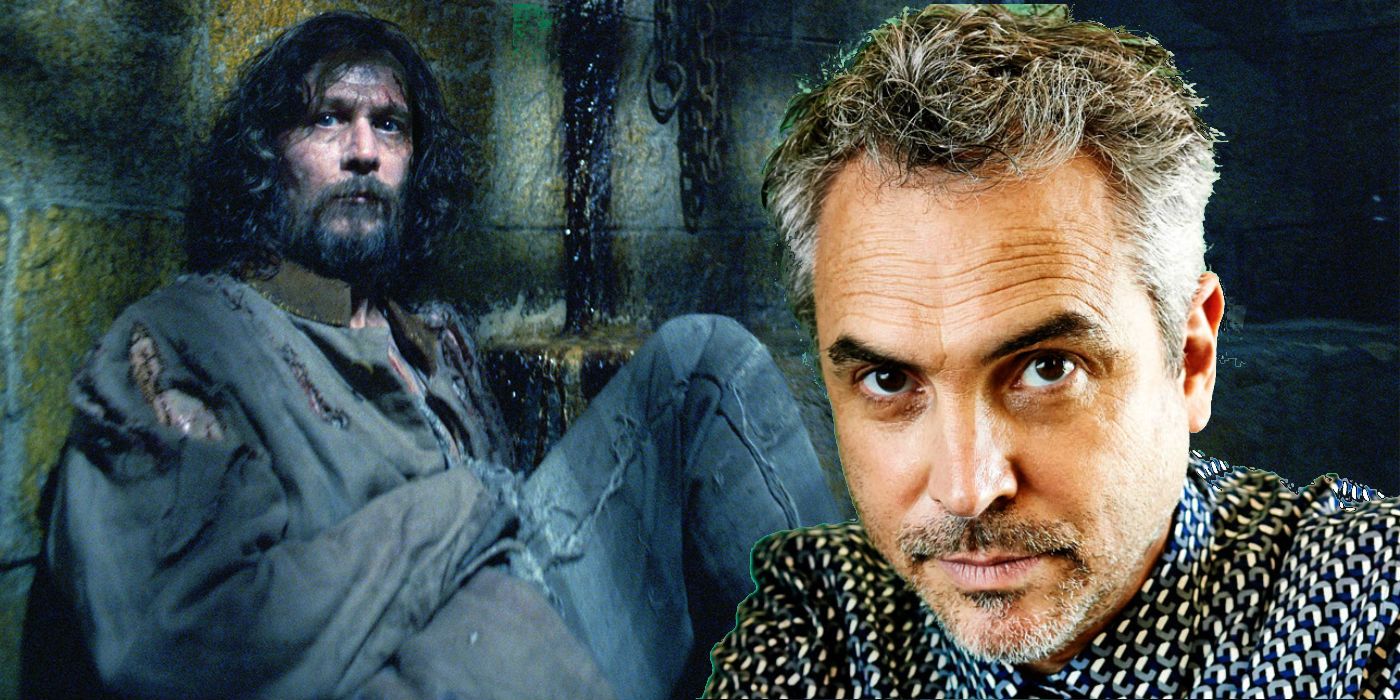

When Chris Columbus walked away from the director's chair after Chamber of Secrets, the Harry Potter franchise was at a crossroads. It was successful, sure. But it was also kinda stiff. The first two films were literal, bright, and—honestly—a bit like watching a filmed version of a theme park ride. Then came the Prisoner of Azkaban director, Alfonso Cuarón. He didn't just change the color palette; he blew up the entire visual language of the Wizarding World.

He almost didn't take the job.

Cuarón hadn't even read the books when he was approached. He famously told his friend Guillermo del Toro about the offer, and del Toro—in his typical blunt fashion—called him an "arrogant bastard" for not jumping at the chance to direct such a massive cultural phenomenon. So, Cuarón read them. He got it. He saw the darkness, the puberty, and the genuine fear that J.K. Rowling had baked into the third installment.

What we got in 2004 wasn't just another sequel. It was a tonal shift that probably saved the franchise from becoming a repetitive relic of the early 2000s.

The Homework Assignment That Changed Everything

One of the most famous stories about the Prisoner of Azkaban director involves a simple writing prompt. Cuarón wanted to know who his lead actors were as people, not just as child stars. He asked Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint to write an essay about their characters.

Their responses were perfectly in character.

Emma Watson turned in a sixteen-page novella about Hermione. Daniel Radcliffe wrote a solid, thoughtful one-page summary of Harry's internal struggle. Rupert Grint? He didn't turn one in at all. When Cuarón asked why, Rupert basically said, "Ron wouldn't do it, so I didn't either." Cuarón loved it. He didn't get mad; he realized he was working with actors who finally understood the skin they were in.

📖 Related: Colin Macrae Below Deck: Why the Fan-Favorite Engineer Finally Walked Away

This level of character depth is why Azkaban feels different. The kids aren't wearing those pristine, stiff Hogwarts robes anymore. They’re wearing hoodies. They have messy hair. Their ties are undone. They look like actual teenagers, not polished dolls in a shop window. Cuarón insisted on this "lived-in" feel because he knew that if the audience didn't believe the kids were real, they wouldn't believe the Dementors were real either.

Shaking the Camera and the Status Quo

Visually, the Prisoner of Azkaban director brought a cinematographer’s eye that the series desperately lacked. He brought in Emmanuel Lubezki’s influence (though Michael Seresin was the DP on record) and utilized long, sweeping tracking shots.

Think about the scene in the Leaky Cauldron.

The camera doesn't just sit there. It weaves through the room, follows characters, and makes the world feel like it exists beyond the edges of the screen. It’s claustrophobic and kinetic. Compare that to the static, wide-angle shots of the first two movies. It’s night and day. Cuarón used wide lenses to keep the background in focus, reminding us constantly that the Wizarding World is a dangerous, bustling place.

He also moved the location of Hagrid’s hut.

In the first two films, it was on flat ground near the castle. Cuarón moved it down a steep, rocky hill. Why? Because it looked cooler. It added scale. It made the journey to see Hagrid feel like an actual trek through the Scottish Highlands. He wasn't afraid to break the internal logic of the previous films to make a better movie.

👉 See also: Cómo salvar a tu favorito: La verdad sobre la votación de La Casa de los Famosos Colombia

Dealing with the Dementors and True Fear

The Dementors were a massive technical hurdle. Originally, Cuarón experimented with puppets underwater to get that slow, ethereal floating movement. It looked incredible, but it was practically impossible to film at scale. Eventually, they moved to CGI, but they kept that "underwater" physics.

The result was terrifying.

These weren't just guys in capes. They were literal voids of soul-sucking depression. The Prisoner of Azkaban director understood that the third book is really about trauma. Harry isn't just fighting a monster; he's fighting his own memories of his mother’s death. Cuarón leaned into the shadows. He used a muted, silvery-blue color grade that made the world feel cold—literally. When the Dementors appear on the Hogwarts Express and the water freezes on the window, you feel that drop in temperature in your living room.

The Michael Gambon Transition

We have to talk about Dumbledore.

After the passing of Richard Harris, the production had to find a new headmaster. Cuarón helped usher in Michael Gambon’s version of the character. This wasn't the "twinkling eye" Dumbledore of the first two films. Gambon’s Dumbledore was a bit eccentric, slightly disheveled, and far more mysterious.

Some fans hated it. They thought he was too intense. But for the story Cuarón was telling—a story about the world getting darker and the adults being unable to protect the children—Gambon was the right fit. He felt like a wizard who had seen some things. He felt like a man who knew a war was coming.

✨ Don't miss: Cliff Richard and The Young Ones: The Weirdest Bromance in TV History Explained

Why Azkaban Is Still the Critics' Favorite

If you poll film nerds, Prisoner of Azkaban usually sits at the top of the list. It’s the "prestige" Harry Potter movie. This is largely because the Prisoner of Azkaban director didn't treat it like a children's movie. He treated it like a piece of European cinema that happened to have magic in it.

He used the Whomping Willow as a seasonal marker. It wasn't just a prop; it was a character that showed the passage of time, shedding leaves and shivering in the snow. It’s these small, artistic flourishes that gave the film a soul.

The clock tower sequence is another masterclass. The use of gears and ticking throughout the film foreshadows the Time-Turner finale perfectly. It’s a rhythmic, visual motif that ties the whole narrative together. Most directors would just show a clock. Cuarón made the entire movie feel like it was ticking toward a deadline.

The Legacy of a One-Off

Cuarón didn't stay for Goblet of Fire. He came, he revolutionized the aesthetic, and he left. Mike Newell and later David Yates inherited the world he built. You can see his fingerprints on every movie that followed. The darker tone, the casual clothing, the focus on the emotional interiority of the trio—all of that started with the Prisoner of Azkaban director.

He proved that you could make a "blockbuster" that was also "art."

He didn't pander to the audience. He assumed kids could handle a bit of sophisticated filmmaking. He was right. Azkaban might not be the highest-grossing film in the series, but it is undeniably the most influential. It turned a franchise into a saga.

How to Appreciate the Director's Cut (In Your Own Mind)

To truly see what Alfonso Cuarón did for the series, try these steps next time you watch:

- Watch the background. In almost every scene at Hogwarts, there is something weird happening in the distance—students playing, ghosts drifting, or magical artifacts moving. This "deep staging" was a Cuarón staple.

- Focus on the transitions. Look at how he uses the bird flying into the Whomping Willow or the reflection in a glass to move from one scene to the next. It's seamless.

- Listen to the score. John Williams stayed on for this film, but Cuarón pushed him toward a more medieval, percussive sound. It’s less "John Williams" and more "Hogwarts."

- Compare the robes. Look at the difference between the ending of Chamber of Secrets and the beginning of Azkaban. The transition from childhood to adolescence is literally woven into the costumes.

If you're looking to dive deeper into film theory, studying Cuarón's use of long takes in this film is a great entry point before moving on to his more complex work like Children of Men or Gravity. You'll see the exact same DNA—a director obsessed with space, time, and how characters move through their environment.