Imagine being born the most powerful baby on the planet. Your father has just conquered the known world, from the rugged mountains of Greece to the humid edges of the Indus River. But there's a catch. Your father is already dead.

That was the reality for Alexander IV of Macedon.

Born in late 323 or early 322 BC, this kid didn't just inherit a kingdom; he inherited a target on his back the size of a phalanx. For thirteen years, he was the center of a bloody, global game of chess played by men who had grown old and hardened under his father, Alexander the Great.

They called these men the Diadochi—the Successors. Honestly, "vultures" might be a more accurate term.

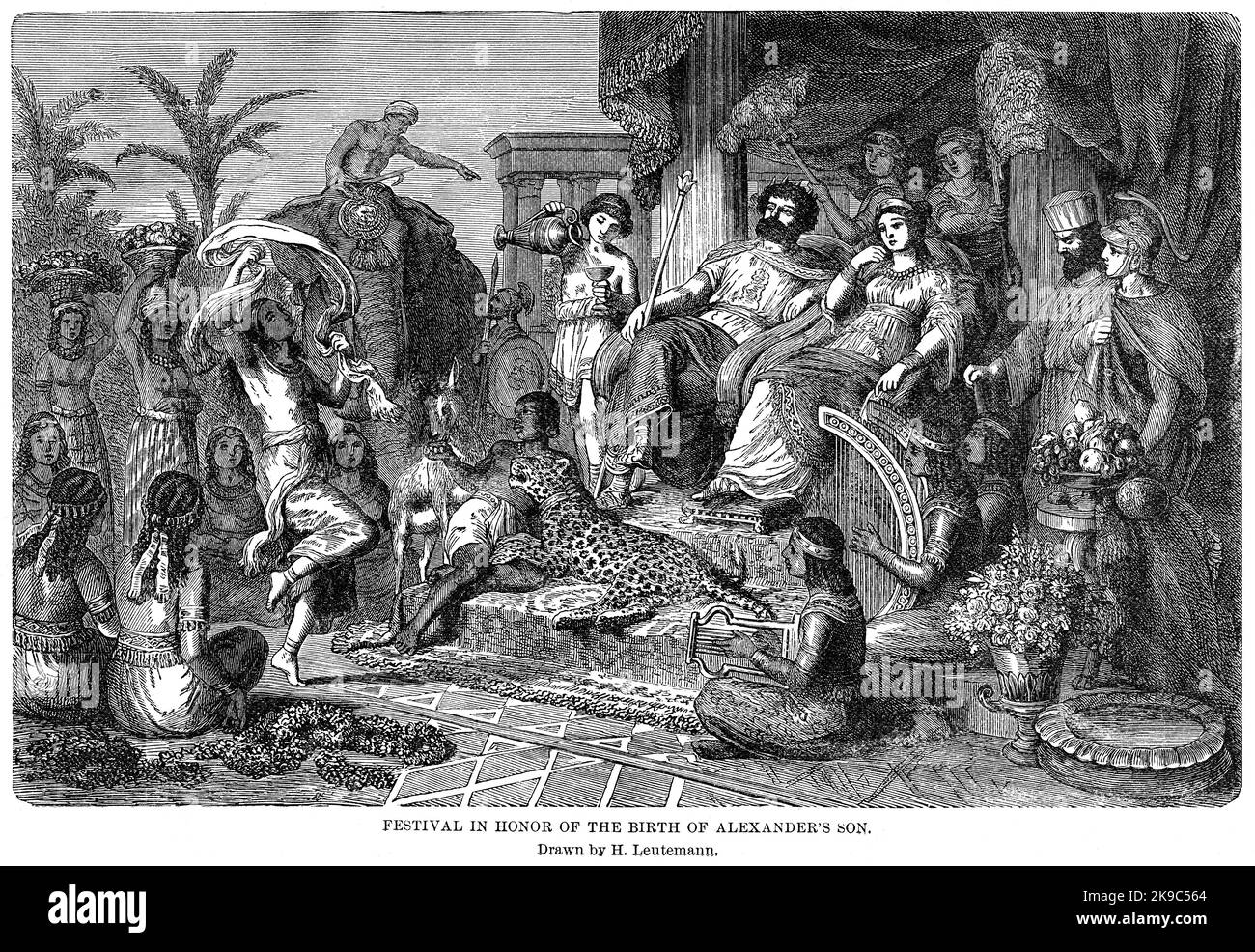

The Birth of a Pawn

When Alexander the Great died in Babylon in June 323 BC, he left a mess. His wife, the Bactrian princess Roxana, was roughly six or eight months pregnant. The Macedonian army was instantly divided. You had the infantry, who wanted Alexander's half-brother, Philip III Arrhidaeus, to take the throne. The problem? Arrhidaeus was mentally incapacitated.

On the other side, the elite cavalry—the Companions—wanted to wait for Roxana’s baby. They struck a deal: if the baby was a boy, he and his uncle Arrhidaeus would rule together.

Basically, the empire was being run by a committee of generals who hated each other, using a disabled man and a newborn infant as legal shields.

🔗 Read more: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

Alexander IV never had a childhood. He was a symbol. A political chip. A reason for generals like Perdiccas or Antipater to claim they were "protecting the royal line" while they actually carved up the map for themselves.

Living in the Shadow of the Lion

By the time Alexander IV was a toddler, the empire was already fracturing. His first "protector," Perdiccas, was murdered by his own officers in Egypt. Then came Antipater, an old-school Macedonian who dragged the boy and his mother back to Europe.

Things got weirdly personal after Antipater died in 319 BC. Instead of leaving the regency to his son, Cassander, he gave it to a general named Polyperchon.

Cassander was furious. He felt cheated.

This sparked a civil war that saw the young King Alexander IV moved around like a piece of luggage. At one point, his grandmother—the terrifying and brilliant Olympias—got involved. She allied with Polyperchon, took the field with an army, and managed to capture the co-king, Philip III Arrhidaeus.

She didn't hesitate. She had Arrhidaeus and his wife executed in 317 BC.

💡 You might also like: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

For a brief moment, five-year-old Alexander IV was the sole King of Macedon. But his grandmother's victory was short-lived. Cassander returned, besieged them at Pydna, and executed Olympias.

The Fortress of Amphipolis

This is where the story gets dark. Cassander didn't kill the boy immediately. That would have caused a riot. Instead, he took Alexander IV and Roxana to the citadel of Amphipolis.

He stripped them of their royal status.

He gave orders that the boy should be treated as a commoner.

No more royal tutors. No more silk. No more "Your Majesty."

For years, the rightful ruler of the world lived in a glorified prison. Meanwhile, the generals were getting tired of pretending. In 311 BC, they signed a peace treaty. It explicitly stated that Cassander would rule Macedonia until Alexander IV came of age.

That was the kid's death warrant.

In Macedonian culture, 14 was the magic number. That was the age a noble boy became a court page and began his transition to adulthood. As the year 309 BC approached, the people of Macedon started whispering. They wanted their king. They wanted the son of the Great Alexander to finally take his seat.

📖 Related: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

The Secret Murder in 309 BC

Cassander knew his time was up unless he acted. He sent a man named Glaucias to the citadel with a simple, horrific order.

Most historians, including N.G.L. Hammond and F.W. Walbank, agree that late in the summer of 309 BC, Alexander IV and his mother Roxana were poisoned.

It was a quiet exit for the last of the Argead dynasty. No battle. No glory. Just a cup of tainted wine or a bowl of seasoned food in a cold stone room. Their bodies were buried secretly to avoid a public outcry, though many believe the "Prince's Tomb" discovered at Vergina in the 1970s actually belongs to him.

The silver urn found there contained the remains of a boy about 13 or 14 years old. The bones showed he hadn't reached full physical maturity. It's a haunting site—lavish decorations for a boy who never got to wear the crown he was born for.

Why Alexander IV Still Matters

We focus so much on the father that we forget the tragedy of the son. Alexander IV represents the "what if" of history. If he had lived, would the empire have stayed together? Probably not. The generals were too far gone.

But his death changed everything. Once the direct line of Alexander the Great was extinct, the generals stopped pretending. Within a few years, they all declared themselves "Kings." The Hellenistic age truly began not with Alexander’s death, but with the murder of his son.

If you're looking for the real "end" of the Golden Age of Macedon, it isn't 323 BC in Babylon. It's 309 BC in Amphipolis.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

- Visit Vergina: If you're ever in Greece, go to the Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai. Seeing the "Prince's Tomb" (Tomb III) gives you a visceral sense of the scale of this tragedy.

- Read the Diadochi Sources: To understand the chaos the boy lived through, look into Diodorus Siculus (Library of History, Books 18-20). He’s the main source for this messy period.

- Question the "Legitimacy" Narrative: Think about how the generals used Alexander IV’s "mixed" heritage (half-Bactrian) to undermine him. It's a classic example of using ethnicity as a political weapon.

- Look at the Coins: Check out the coinage from 323–310 BC. You’ll see "Alexander" written on them, but it’s often unclear which Alexander the mint was honoring—the dead father or the captive son.

The story of Alexander IV is a reminder that in the ancient world, being a "chosen one" was usually a death sentence. He was the king of everything and the master of nothing.