He wasn't actually born with the middle name Graham.

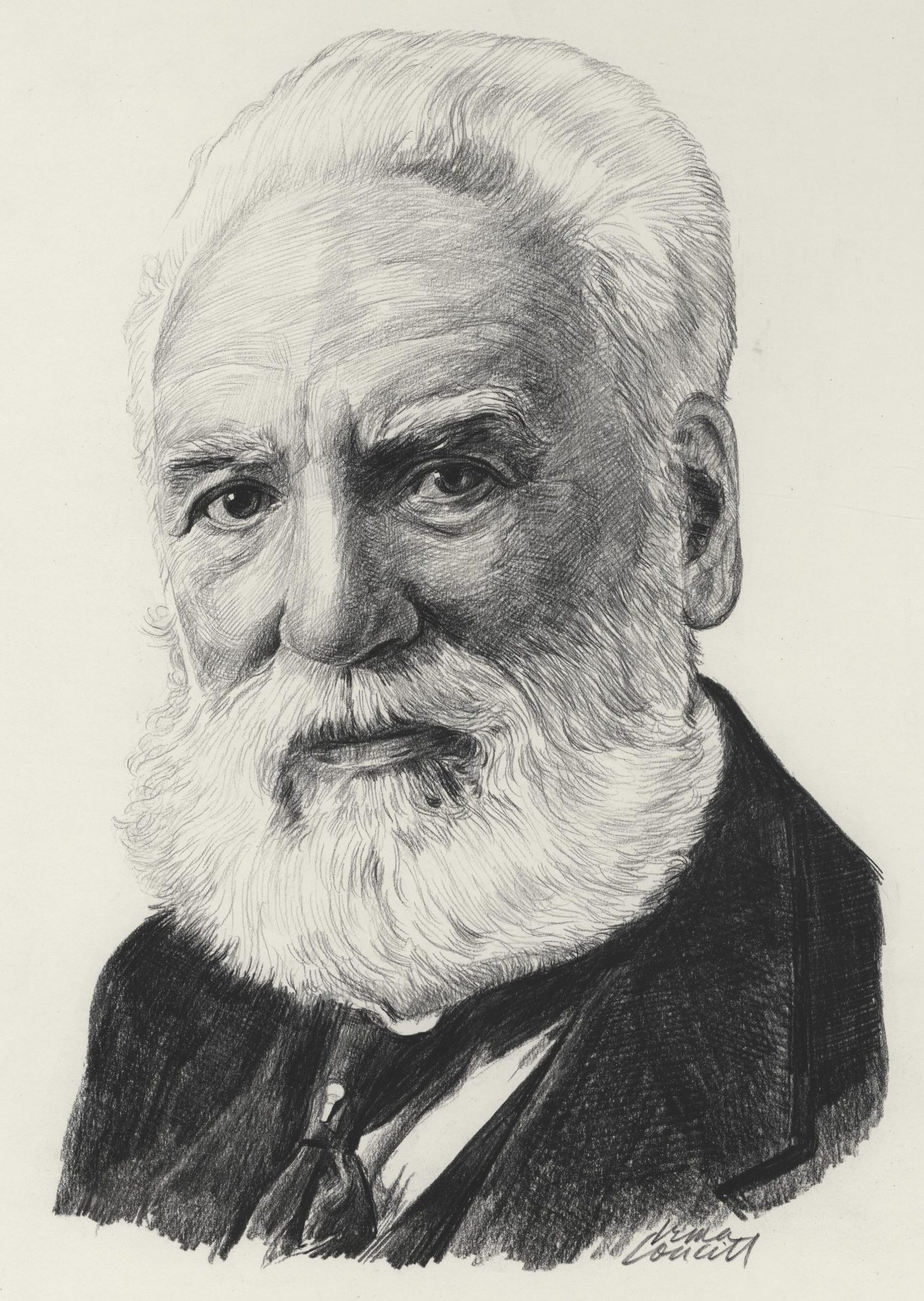

Alexander Bell entered the world on March 3, 1847, in a modest house at 16 South Charlotte Street in Edinburgh, Scotland. If you look at his birth record, it’s just Alexander Bell. Plain. Simple. It wasn't until he turned eleven that he begged his father for a middle name to match his brothers, Melville and Edward. He chose "Graham" out of respect for Alexander Graham, a family friend and former student of his father. It’s a tiny detail, but it says a lot about his personality—even as a kid, he wanted to stand out and define himself.

The story of alexander graham bell by birth isn't just a trivia point for history buffs; it’s the foundation of everything he eventually built. Most people think of him as an American inventor, or maybe Canadian because of his time in Ontario. But his DNA—both biological and intellectual—is purely Scottish. He grew up in the "Athens of the North" during a time when Edinburgh was a powerhouse of scientific thought and rigorous education.

The Sound of the Bell Family

Sound was the family business. Seriously.

His grandfather was a shoemaker who became an actor and then a speech teacher. His father, Alexander Melville Bell, was a world-famous elocutionist who created "Visible Speech," a system of symbols used to help the deaf learn to speak by visualizing how the tongue and throat should move. This wasn't some hobby. It was a mission. Young Aleck, as his family called him, was surrounded by the mechanics of the human voice from his first breath.

Imagine a house where people aren't just talking, but analyzing how they talk. That was the Bell household.

By the time he was a teenager, Aleck was already experimenting. He and his brother once tried to build a "speaking machine"—a mechanical head with a larynx and moving lips. They actually got it to say "mama" well enough that neighbors came over to see what the fuss was about. This obsession with the physical reality of sound is exactly why he later understood how to turn sound waves into electrical impulses. He didn't just "invent" the telephone; he translated his father's work on speech into the language of electricity.

✨ Don't miss: When Can I Pre Order iPhone 16 Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Scotland Matters to the Invention

If Bell hadn't been Scottish by birth, the telephone might not exist. At least, not in the way we know it.

The Scottish Enlightenment had left a deep mark on the education system in Edinburgh. It encouraged a specific kind of "practical tinkering." You weren't just supposed to read books; you were supposed to pull things apart to see how they worked. Bell attended the Royal High School in Edinburgh, and honestly? He hated it. He found the curriculum boring. He was a classic case of a brilliant mind being stifled by rigid, traditional schooling. He preferred wandering through the Scottish hills or playing the piano.

But that frustration drove him toward self-study. He was mostly homeschooled by his mother, Eliza Grace Symonds. Here's a detail people often miss: Eliza was nearly deaf.

Think about that. The man who gave the world the telephone—a device purely for hearing—spent his formative years finding ways to communicate with a mother who lived in silence. He would speak close to her forehead so she could feel the vibrations of his voice. That intimate, physical connection to sound frequency is something you can't learn in a textbook. It was born into him.

The Tragedy that Forced a Move

Everything changed in his early twenties. The Bell family was hit by a brutal streak of tuberculosis. Both of Aleck's brothers died from the disease. Fearing for their only surviving son's life, his parents decided to leave the damp, soot-heavy air of industrial-era Britain.

They moved to Canada in 1870.

🔗 Read more: Why Your 3-in-1 Wireless Charging Station Probably Isn't Reaching Its Full Potential

This is the pivot point. When we talk about alexander graham bell by birth, we have to acknowledge that his departure from his homeland was an act of survival. He brought the Scottish obsession with elocution to the New World, where the wide-open patent markets and the influx of capital allowed his ideas to explode. He settled in Boston eventually, but he never lost that clipped, precise Scottish accent or the specific scientific methodology he learned in Edinburgh.

The Deafness Connection and the Patent Wars

We need to be real about Bell's legacy because it’s complicated.

In the modern world, Bell is sometimes a controversial figure in the Deaf community. While he dedicated his life to helping the deaf, he was a staunch advocate for "oralism"—the idea that deaf people should learn to speak and lip-read rather than use sign language. Because of his background with Visible Speech, he viewed deafness as a problem to be "solved" through technology and training.

Whether you agree with his methods or not, his work at the Boston University School of Oratory is what funded his late-night experiments. He was working on a "harmonic telegraph"—a way to send multiple messages over one wire—when he realized he could transmit the entire human voice.

On March 10, 1876, he finally did it. "Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you."

It’s a famous line, but the technical brilliance behind it was decades in the making. It required an understanding of how membranes (like the human eardrum) vibrate. He knew how eardrums worked because his father had literally written the book on vocal physiology back in Scotland.

💡 You might also like: Frontier Mail Powered by Yahoo: Why Your Login Just Changed

Myths vs. Reality

People love to argue about who actually invented the telephone. Was it Elisha Gray? Antonio Meucci?

Here's the nuance: Bell was the first to get the patent, and he was the one with the most cohesive scientific theory. Gray arrived at the patent office just hours after Bell's lawyer. It was one of the most famous legal battles in American history. Bell eventually won because his notes were meticulously detailed—a habit he picked up from the rigorous scientific community in Edinburgh.

It wasn't just luck. It was the result of a lifelong obsession that started in a small room in Scotland.

Making the Connection Today

If you want to truly understand the impact of Bell's origins, you have to look at the sheer variety of his interests. He didn't stop at the phone. He worked on hydrofoils, aeronautics (the Silver Dart!), and even a primitive version of a metal detector to try and save President James Garfield’s life after he was shot.

His brain was wired for "what if."

That restless, polymath energy is the hallmark of the Scottish intellectual tradition. He was a man of the world, but he was always the boy from South Charlotte Street.

Actionable Takeaways for History and Tech Enthusiasts

To get the most out of studying Bell's life and the evolution of communication, consider these steps:

- Trace the lineage of "Visible Speech": Look up Alexander Melville Bell’s phonetic symbols. Understanding how Bell visualized sound helps you understand how modern digital signal processing (DSP) works. It’s all about breaking waves into data.

- Visit the source: If you’re ever in Edinburgh, visit the memorial at his birthplace. It’s a reminder that global revolutions often start in small, quiet places.

- Explore the Bell-Meucci debate: Read the 2002 U.S. House of Representatives resolution regarding Antonio Meucci. It provides a fascinating look at how patent law and history can sometimes disagree.

- Study the "Harmonic Telegraph": Before the phone, Bell was trying to solve a bandwidth problem. The logic he used to try and send multiple signals over one wire is the direct ancestor of how your fiber-optic internet works today.

- Acknowledge the complexity: Dig into the history of the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf (now the Alexander Graham Bell Association). It helps provide a balanced view of his contributions to education versus his controversial views on sign language.

Bell’s life proves that where you come from dictates how you see the world. By birth, he was a student of sound. By necessity, he became an immigrant. By genius, he became the architect of the connected world.