Alexander Graham Bell didn’t just wake up one day and build a phone. Honestly, the story we’re told in elementary school—the one where he spills acid, yells for Mr. Watson, and suddenly the world is connected—is a massive oversimplification of a very messy, very litigious, and very loud history.

It was 1876.

The air in Boston was thick with the smell of industrial coal and the frantic energy of the Second Industrial Revolution. Bell was a teacher of the deaf, a man obsessed with the mechanics of sound because his mother was nearly deaf and his father had literally invented a universal alphabet called "Visible Speech." He wasn't some tech bro looking for a payday. He was trying to solve a human problem. But the inventor of the telephone found himself in a cutthroat race against Elisha Gray and Antonio Meucci that would eventually lead to the most famous patent battle in American history.

The race to the patent office

People think patents are boring. In this case, they were a blood sport. On February 14, 1876, Bell’s lawyer filed a patent application for the telephone. Just a few hours later, a guy named Elisha Gray filed a "caveat"—basically a placeholder for an invention—for a strikingly similar device.

Think about that timing.

A few hours determined who would become a billionaire and who would become a footnote. There is still a lot of drama among historians about whether Bell’s lawyers got a "sneak peek" at Gray’s filing. Some researchers, like Seth Shulman in his book The Telephone Gambit, argue that Bell actually lifted the idea for a liquid transmitter from Gray’s sketches.

It’s complicated.

Bell’s successful demonstration used a different method than his final production models, but the patent office moved fast. By March, Bell had his patent. By June, he was showing it off at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, where the Emperor of Brazil reportedly dropped the receiver and shouted, "My God, it talks!"

It wasn't just about the wires

Most people assume the inventor of the telephone was just a gearhead. He wasn't. Bell was deeply rooted in the science of "harmonic telegraphy." At the time, the big money was in the telegraph. Companies like Western Union were the Googles of the 19th century. The problem was that telegraph wires could only send one message at a time.

Bell thought he could send multiple messages at different pitches.

While trying to figure out how to send multiple "notes" down a wire, he realized he could send the human voice itself. It’s a classic case of looking for one thing and finding something infinitely better. You’ve probably heard the phrase "Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you." That was the first successful transmission. But what's rarely mentioned is that the device they used was incredibly fickle. If the weather was too humid or the acid in the battery was too weak, it was just expensive junk.

The Antonio Meucci controversy

If you go to Staten Island, you’ll hear a different story. Long before Bell, an Italian immigrant named Antonio Meucci was working on a "teletrofono."

Meucci was a genius, but he was broke.

👉 See also: TV Wall Mounts 75 Inch: What Most People Get Wrong Before Drilling

He had a working prototype in his home to talk to his wife, who was paralyzed by arthritis. He filed a caveat in 1871—five years before Bell—but he couldn't afford the $10 fee to renew it in 1874. In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives actually passed a resolution acknowledging Meucci’s contributions, which caused a bit of a stir in the scientific community. Does that make Bell a fraud? Not necessarily. Bell had the vision to scale it, the funding to back it, and the legal team to defend it.

Innovation is rarely a solo act. It’s usually a relay race where the person who crosses the finish line gets all the medals.

Why the technology actually worked

The technical leap Bell made was moving from "make-and-break" currents to "undulating" currents. Early inventors tried to turn the electricity on and off rapidly to mimic sound waves. It sounded like static.

Bell realized you needed a continuous current that varied in intensity.

Imagine a wave in the ocean. Instead of just splashing water (on/off), he was changing the height of the wave smoothly. This allowed the diaphragm in the receiver to vibrate in a way that mimicked the human ear. It was elegant. It was also incredibly difficult to manufacture at scale. The first phones didn’t have a ringer. You just had to hope someone was listening on the other end, or you had to shout until they heard you.

The business of being the inventor of the telephone

Western Union had a chance to buy Bell’s patent for $100,000. They said no.

✨ Don't miss: Why It’s So Hard to Ban Female Hate Subs Once and for All

The president of Western Union, William Orton, famously called the telephone a "toy." That is arguably the worst business decision in the history of the United States. Within a few years, Bell’s company (which became AT&T) was dismantling Western Union's monopoly.

Bell himself actually grew to hate the phone. He refused to have one in his study because it was too distracting. He wanted to focus on his work with the deaf and his experiments with flight. By the time he died in 1922, the telephone had changed the world, but Bell had moved on to hydrofoils and giant tetrahedral kites.

When he was buried, every phone in North America was silenced for one minute.

What you can learn from Bell’s process

Looking back at the inventor of the telephone, there are some pretty practical takeaways for anyone trying to build something new today.

- Solve for an edge case: Bell wasn't trying to build a mass-market communication tool for businessmen; he was trying to help people with hearing loss. Often, solving a specific, difficult problem leads to a universal solution.

- Documentation is everything: Bell won over 600 lawsuits because his lab notebooks were meticulous. If you’re creating something, write it down. Date it. Witness it.

- Persistence over perfection: The first phone calls were barely audible. If Bell had waited until the audio was "HD quality," someone else would have grabbed the patent.

- Understand the legal landscape: You can be the smartest person in the room, but if you don't understand patent law (or have someone who does), you'll lose your shirt.

The history of the telephone is a reminder that being "first" is often a matter of debate, but being "the one who makes it work for the world" is what sticks in the history books.

Practical next steps for history and tech enthusiasts

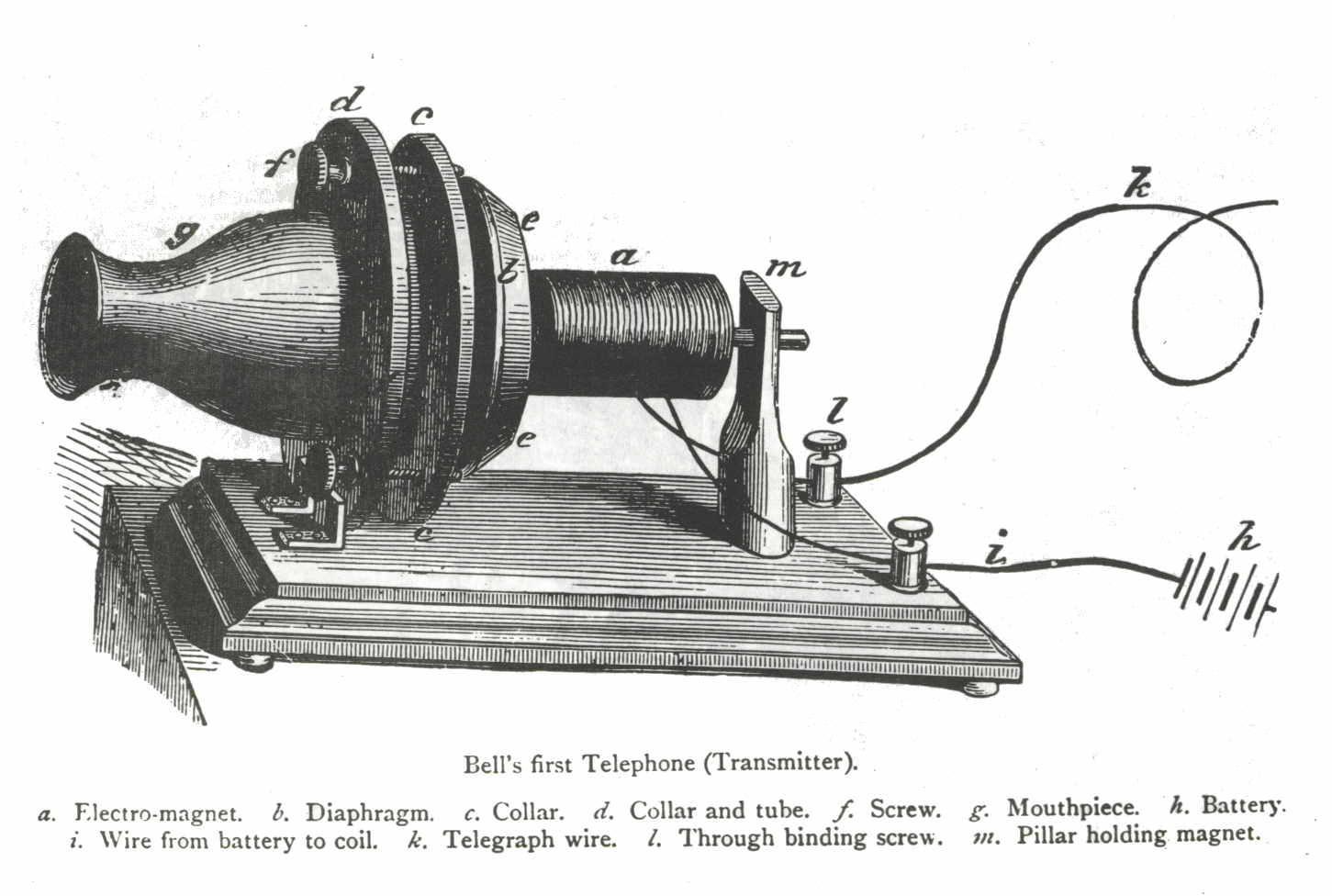

If you want to dive deeper into how this actually happened, start by looking at the original patent diagrams (U.S. Patent 174,465). They are surprisingly simple. You can also visit the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, where many of his original models are kept. For a more critical view of the "great man" theory of invention, read The Telephone Cases (1888), which details the Supreme Court battle that nearly stripped Bell of his title. This research highlights that technology is never just about wires—it's about law, timing, and sheer luck.