The sound is unmistakable. It’s a low, guttural wail that cuts through the salt air in coastal towns from Ketchikan to Adak. If you live in Alaska, that sound triggers an immediate, visceral reaction. You don't think; you move. A tsunami warning for Alaska isn't some abstract weather advisory you can ignore while finishing your coffee. It is a high-stakes race against physics.

Living on the Pacific Ring of Fire means we are essentially sitting on a geologic powder keg. About 75% of all U.S. earthquakes with a magnitude greater than 5 occur in Alaska. We have the Aleutian Trench—a 2,500-mile-long underwater canyon where the Pacific Plate is ruthlessly shoving itself under the North American Plate. When that subduction zone snaps, the ocean doesn't just ripple. It displaces.

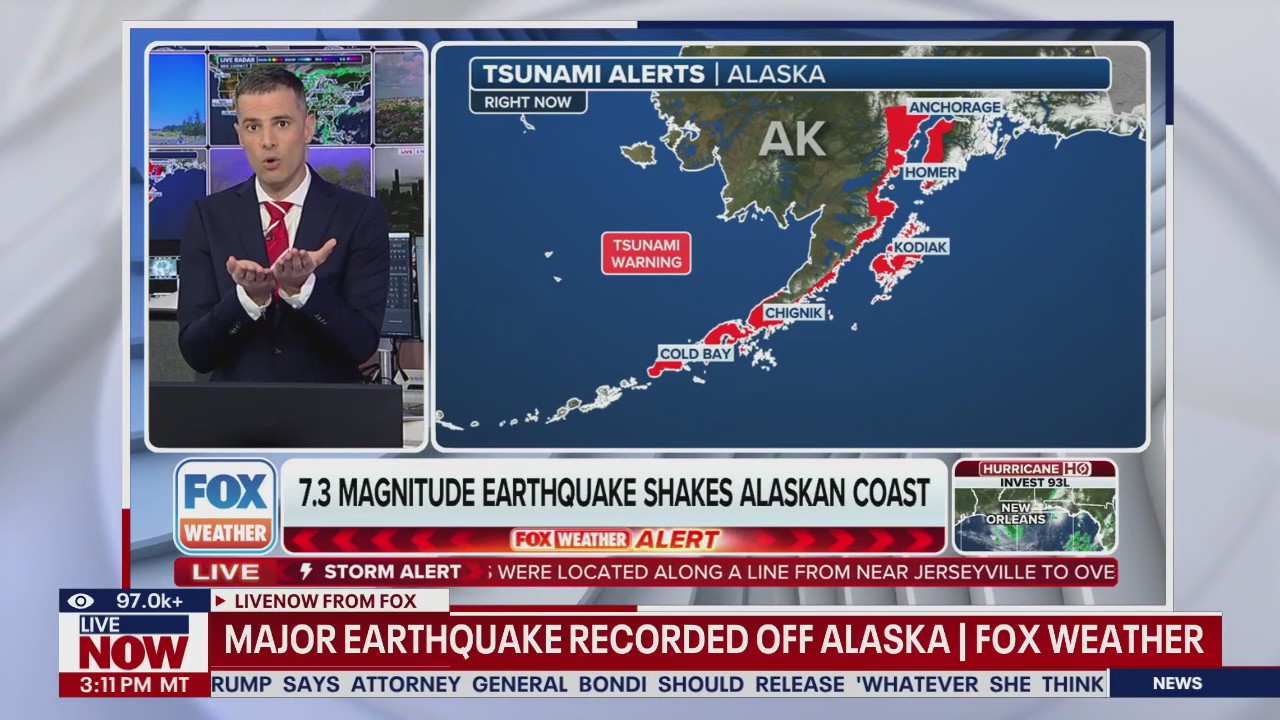

I’ve talked to people who were in Kodiak during the 2018 magnitude 7.9 quake. It happened at 12:31 a.m. People were jolted out of bed, threw kids into trucks, and drove toward Pillar Mountain in the pitch black. There was no "official" confirmation for those first few minutes, just the shaking and the terrifying knowledge of what usually comes next. That’s the reality of life up here. You don’t wait for the text alert. The earthquake is your warning.

How the National Tsunami Warning Center Decides Your Fate

When the ground shakes, a clock starts ticking at the National Tsunami Warning Center (NTWC) in Palmer, Alaska. They are the gatekeepers. Within roughly five minutes of a major quake, the scientists there have to decide if they’re going to trigger a tsunami warning for Alaska or a less severe "advisory."

It’s a massive responsibility. If they call it too early and nothing happens, people get "warning fatigue" and might ignore the next one. If they wait too long to be sure, people die.

They use a network of deep-ocean pressure sensors called DART (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis) buoys. These things are incredible. They sit on the seafloor and can detect a wave height change of less than a millimeter in the open ocean. When a buoy senses that pressure change, it beams the data to a satellite, which kicks it back to Palmer.

But here’s the kicker: near-shore residents don't have time for buoy data. If you are in a place like Seward or Whittier and a massive quake hits nearby, the wave could arrive in ten minutes. The NTWC has to issue that initial warning based almost entirely on seismic data—the location, depth, and magnitude of the quake—before they even see a wave on a sensor.

👉 See also: Trump First Day Orders: What Really Happened on Day One

The Difference Between a Warning, an Advisory, and a Watch

Honestly, the terminology can be confusing when you’re panicking and looking for your car keys. Let’s break it down simply.

A Warning is the big one. It means a dangerous tsunami is "imminent, expected, or occurring." This is when the sirens go off. This is when you get to high ground immediately. We’re talking about widespread flooding and powerful currents that can grind a harbor to splinters.

An Advisory is a bit different. It usually means "stay out of the water." You might see strong currents and some localized flooding on beaches, but they aren't expecting the town to get leveled. You should still get off the docks, but you probably don't need to evacuate to the mountains.

Then there’s a Watch. This is basically the "stand by" phase. An earthquake happened, and the NTWC is checking the buoys to see if a wave was actually generated. It hasn’t been confirmed yet, but you should be ready to move.

Why Some Tsunami Warnings Feel Like False Alarms

You’ve probably seen the headlines. A massive quake hits, the sirens scream, people spend four hours in their cars on a hilltop, and then... nothing. The warning is canceled.

Was it a mistake? Not really.

Tsunami science is getting better, but it’s still not perfect. Sometimes a magnitude 8.0 quake is "strike-slip," meaning the plates slide past each other horizontally. This doesn't move much water, so there’s no big wave. But the NTWC often has to issue the tsunami warning for Alaska based on the magnitude before they know the exact "mechanism" of the quake. They err on the side of saving lives.

Also, local geography changes everything. A wave that is only six inches high in the open ocean can grow to thirty feet when it gets funneled into a narrow bay or inlet. This is called "run-up." Because Alaska’s coastline is a mess of fjords and islands, predicting exactly how a wave will behave in every single cove is nearly impossible.

The Ghost of 1964: Why Alaskans Don't Mess Around

Everything we know about tsunamis in this state is colored by the Great Alaska Earthquake of 1964. It was a 9.2 magnitude beast—the second-largest earthquake ever recorded.

It didn't just cause one tsunami; it caused dozens. The main tectonic tsunami hit the coast, but the shaking also caused "local landslides" that triggered immediate, massive waves. In Chenega, a village in Prince William Sound, a wave wiped out over half the population within minutes.

Valdez was essentially destroyed. The waterfront literally slid into the sea. This is why Alaskans have a collective memory of the water. We know that the ocean can become a wall of debris, houses, and boats in the blink of an eye.

Modern infrastructure is better, sure. Our buildings are bolted down more securely. But the power of moving water is absolute. A cubic yard of water weighs about 1,700 pounds. If a tsunami is moving at thirty miles per hour and it's full of logs and cars, no building is a safe harbor. High ground is the only harbor.

What You Actually Need in Your Go-Bag

Forget the generic survival lists you see on Pinterest. If you’re dealing with a tsunami warning for Alaska, you need items that handle cold and wet.

- Warmth is priority one. It’s probably going to be 2:00 a.m. It might be snowing. If you’re sitting on a ridge for six hours, you need wool blankets, extra socks, and a real jacket. Hypothermia is a bigger threat than the wave for many people.

- A NOAA Weather Radio. Cell towers often jam up or fail during a disaster. A battery-powered or hand-crank radio will give you the "all clear" when it’s actually safe to come down.

- Prescriptions. This is the one people forget. If you’re evacuated for two days, you need your meds.

- Boots. Don't run out of the house in slippers. There will be glass, debris, and mud.

Real-World Steps to Take Right Now

If the sirens go off or the ground shakes so hard you can't stand, here is the expert-level protocol.

First, get off the beach. If you can see the wave, you are already too close. Most people think they can outrun it in a car, but traffic jams are a death trap in places with limited exit roads like Homer or Seward. If traffic is stalled, get out and climb on foot.

Second, aim for at least 100 feet above sea level. If you can’t get that high, go as far inland as possible. Two miles is the general rule of thumb if the terrain is flat, though "flat" isn't exactly Alaska's specialty.

✨ Don't miss: Top 10 Biggest Tornadoes: What Most People Get Wrong About Size

Third, stay there. Tsunamis are a series of waves, not just one. Often, the second or third wave is much larger than the first. The "trough" of the wave can also cause the ocean to recede dramatically, exposing the seafloor. Do not go down to look at the fish. The water will return with a vengeance.

Wait for the official "All Clear." This can take hours. Local authorities like the Alaska State Troopers or your local PD will broadcast when the danger has passed.

Staying Informed Without the Panic

The best way to handle the next tsunami warning for Alaska is to have the information delivered to you automatically.

- Sign up for Nixle alerts for your specific borough or city.

- Enable Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) on your smartphone. This is the loud "AMBER Alert" style sound that bypasses Do Not Disturb settings.

- Map your route. Go for a drive today. Find out exactly where the "Tsunami Evacuation Route" signs lead in your neighborhood.

- Check the NTWC website. Bookmark tsunami.gov. It is the source of truth for the entire Pacific.

Understand that a warning isn't a guarantee of destruction; it's an opportunity to stay alive. The science is fast, the responders are dedicated, but ultimately, your safety depends on your own feet and your own plan. When the earth moves, move with it—upward.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Check your home's elevation using a topographic map or a GPS app; if you are under 100 feet, identify the nearest point of high ground.

- Place a "Go-Bag" near your front door or in your vehicle containing at least 72 hours of essential medications and cold-weather gear.

- Verify that your smartphone's emergency alert settings are turned ON for "Emergency Alerts" and "Public Safety Messages."

- Identify at least two different routes to high ground in case your primary road is blocked by earthquake damage or landslides.

By taking these steps, you move from being a potential victim to a prepared survivor. In Alaska, that’s just part of the job description for living here.