You’re probably reading this on a device that wouldn’t exist without a man the world tried its hardest to forget. Alan Turing wasn't just a "math guy" or a war hero. He was the literal architect of the digital age, a marathon runner who could’ve been an Olympian, and a victim of a society that didn’t deserve him. Honestly, the more you dig into his life, the more you realize that the movie versions—while great—barely scratch the surface of how weird, brilliant, and tragic his reality actually was.

The 1936 Paper That Changed Everything

Most people think "computer" and picture Silicon Valley in the 70s. Wrong. It started in 1936 with a dense, borderline unreadable paper called On Computable Numbers.

Turing was only 24.

He came up with a "Universal Machine." It wasn't a physical box of gears. It was a thought experiment—a hypothetical device that could read a strip of tape and simulate any other machine. Before this, "computers" were people. Literally. They were rooms full of humans doing long division for hours. Turing said, "What if we make a machine that can do anything a human computer can do?"

That is the birth of software. It’s the idea that a single piece of hardware can become a calculator, then a typewriter, then a game of Solitaire, just by changing the instructions. We take it for granted now, but in 1936, this was basically sorcery.

Cracking the Enigma at Bletchley Park

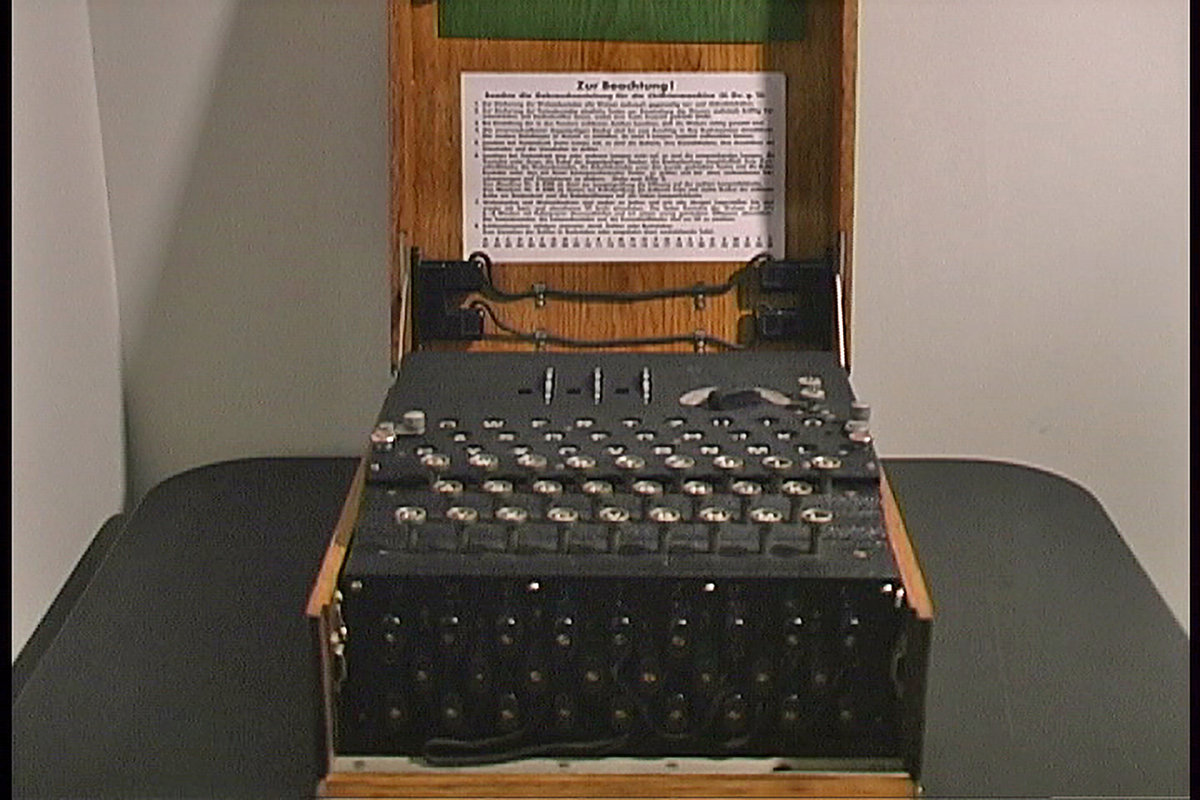

Then came the war. Germany had the Enigma machine, which looked like a typewriter but scrambled messages into 150 quintillion possible combinations. The Nazis changed the settings every single day at midnight.

If you tried to crack it by hand, the sun would burn out before you finished one day's code.

🔗 Read more: Why the Gun to Head Stock Image is Becoming a Digital Relic

Turing didn't just "break a code." He built a beast called the Bombe. This wasn't a computer in the modern sense—it was an electro-mechanical monster of spinning drums and clicking relays. It didn't "think." It searched. It used logic to discard millions of wrong answers in seconds.

By 1943, Bletchley Park was an industrial intelligence factory. They were reading Hitler’s mail before his own generals sometimes. Historians generally agree this shortened the war by at least two years. Think about that. Two years of bombing, starvation, and genocide that didn't happen because of Alan Turing and his team in a drafty hut in the English countryside.

The Myth of the Lone Genius

One thing we get wrong? He wasn't alone. Turing was the "ideas man," but he worked with thousands of people, mostly women from the Women's Royal Naval Service (Wrens), who operated the heavy machinery. It was a massive, collective effort. He was also a bit of a character—he used to chain his coffee mug to the radiator so nobody would "steal" it. He also rode a bicycle with a chain that would fall off every few dozen rotations. Instead of fixing it, he just counted the pedal strokes and hopped off at the exact moment to adjust it.

Classic Turing.

The Turing Test and the "Thinking Machine"

After the war, everyone else wanted to go back to normal. Turing wanted to build a brain. In 1950, he published Computing Machinery and Intelligence. He opened it with a question that still keeps AI researchers up at night: "Can machines think?"

He knew "thinking" was too vague to define. So he made it a game. The Imitation Game.

💡 You might also like: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

If a human is talking to a computer through a screen and can't tell it's a machine, then for all practical purposes, that machine is intelligent. He wasn't interested in the philosophy of "soul" or "consciousness." He was an engineer. If it acts smart, it is smart.

He even predicted that by the year 2000, we’d have machines that could fool a human for five minutes. He wasn't far off. Today, with LLMs and generative AI, we’re living in the world he hallucinated seventy years ago.

A Brutal End to a Brilliant Life

This is where the story gets heavy. In 1952, Turing’s house was burgled. During the police investigation, he was honest about having a relationship with another man, Arnold Murray.

In 1950s Britain, that was a crime.

He was convicted of "gross indecency." He was given a choice: prison or "chemical castration." He chose the latter. They injected him with synthetic estrogen to "cure" his homosexuality. It was barbaric. It ruined his body, his health, and eventually his security clearance. He was banned from doing the very work that had saved the country just a few years earlier.

On June 7, 1954, he was found dead. Cyanide poisoning. There was a half-eaten apple by his bed. The official verdict was suicide, though some of his friends and family argued it was an accident during one of his chemistry experiments.

📖 Related: The Dogger Bank Wind Farm Is Huge—Here Is What You Actually Need To Know

Regardless of the "how," the "why" is obvious. A nation that owed him its survival broke him.

Why Alan Turing: The Enigma Matters Now

It took way too long for the world to say sorry.

- 2009: Gordon Brown issued an official apology.

- 2013: Queen Elizabeth II granted a posthumous Royal Pardon.

- 2017: "Turing’s Law" was passed, pardoning thousands of other gay men convicted under those same archaic rules.

But Turing’s legacy isn’t just about his tragedy. It’s about the sheer audacity of his imagination. He saw the digital world before it had a name. He saw AI before we had transistors.

Actionable Insights from Turing’s Life

If you want to apply "Turing-style" thinking to your own life or work, here is how:

- Reduce to First Principles: When faced with a complex problem (like Enigma), don't look for the "big" answer. Look for the smallest logical rules that govern the system.

- Outcome Over Process: The Turing Test teaches us that it doesn't matter how a machine works internally; what matters is the result it produces for the user.

- Cross-Pollinate: Turing was a mathematician, but he studied biology (morphogenesis) and physics. Innovation usually happens at the intersection of two things that aren't supposed to go together.

- Acknowledge the Human Element: Systems are only as good as the people running them. Turing’s machines needed the Wrens; your tech needs a human touch.

To truly understand our modern world, you have to understand the man who drew the blueprints in a world of paper and pencil. He was the ultimate outlier.

Next Steps:

If you want to dive deeper into the technical side of his work, you should look up the Church-Turing Thesis. It explains why your laptop and your smartphone are essentially the same machine in different clothes. You can also visit Bletchley Park in the UK; it’s a museum now, and seeing the reconstructed Bombe machines in person gives you a visceral sense of the scale of what they achieved.