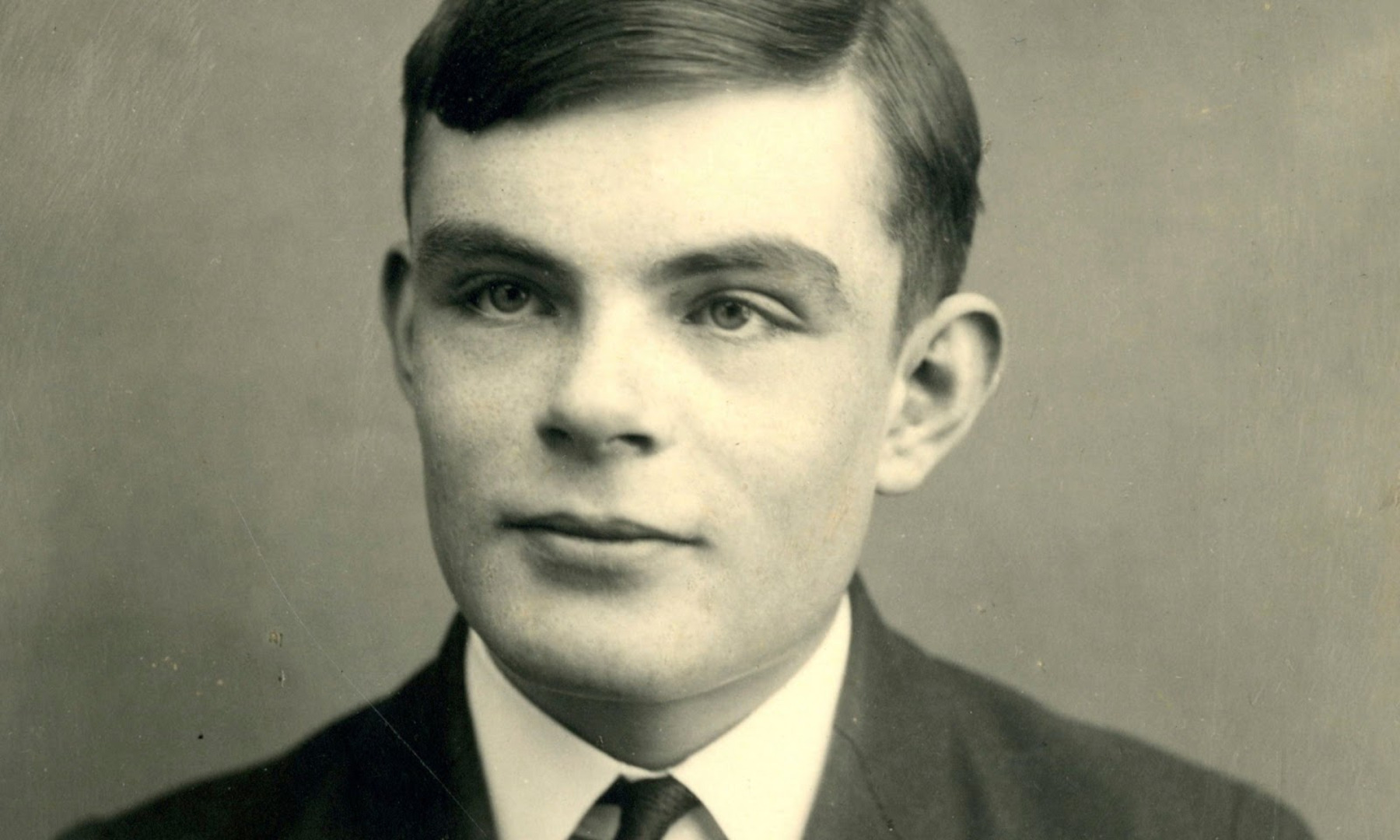

You’ve probably seen the movie. The one where Benedict Cumberbatch frantically scribbles on a chalkboard while a giant mechanical beast clicks in the background. It’s a great story. But honestly? If you think Alan Turing was just "the guy who broke the Enigma code," you're missing the most mind-bending parts of his brain.

His wartime heroics at Bletchley Park saved millions of lives—that is a cold, hard fact. However, in the world of pure mathematics, Turing’s greatest achievement happened years before he ever stepped foot in a secret government bunker. He didn't just build a machine; he defined what it means to "compute" something in the first place.

The Paper That Changed Everything (Before the War)

In 1936, Turing was just 24. He published a paper with a title that sounds like a total snooze-fest: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem.

Don't let the German word scare you. The "Decision Problem" was basically a challenge issued by David Hilbert. Hilbert wanted to know if there was a mechanical process—a "recipe"—that could determine if any mathematical statement was true or false.

Turing said no.

To prove it, he didn't use gears or wires. He used a thought experiment. He imagined an infinite strip of paper tape divided into squares and a "head" that could read, write, or erase symbols.

Why the "Turing Machine" is a Big Deal

- It’s universal. Most machines do one thing (like a toaster). A Turing Machine can be any machine if you give it the right instructions.

- The Halting Problem. Turing proved you can’t write a program that can look at any other program and tell if it will eventually stop or run forever. This is the bedrock of computer science.

- Hardware vs. Software. He was the first to realize that the machine itself doesn't matter as much as the logic you feed it.

Basically, every smartphone, laptop, and AI model in 2026 is just a very fast, very fancy version of that 1936 thought experiment.

📖 Related: Larry Ellison AI Surveillance: Why Your Best Behavior is Now a Business Strategy

The "Other" Alan Turing Mathematical Contributions

Most people stop at the computers. That's a mistake. Late in his life, Turing got obsessed with something totally different: why do leopards have spots?

He called it Morphogenesis.

In 1952, he published The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis. At the time, biologists were looking at DNA (which hadn't even been fully modeled yet). Turing, being a math guy, looked at it through the lens of reaction-diffusion equations.

He proposed that two chemicals—an "activator" and an "inhibitor"—spreading through an embryo could create patterns. One chemical tells the skin to turn dark, the other tells it to stay light. If they move at different speeds, you get stripes, spots, or spirals.

🔗 Read more: Why Every List of Mathematical Symbols Feels Like a Secret Language You Almost Know

It was a radical idea.

Biologists mostly ignored him for decades. But guess what? Modern imaging and genetic sequencing have shown he was right. From the ridges on the roof of your mouth to the scales on a fish, "Turing Patterns" are everywhere in nature. It's biomathematics at its finest.

The Myth of the Lone Genius

We love the "isolated hero" trope. Turing was definitely a unique character—he reportedly chained his coffee mug to the radiator to stop people from stealing it—but he wasn't a hermit.

He worked closely with Alonzo Church at Princeton. In fact, they both arrived at similar conclusions about the Decision Problem at the same time. This is why experts call it the Church-Turing Thesis.

Turing was also a collaborator. At Bletchley, he wasn't just a math monk; he was a leader. He worked with Gordon Welchman to improve the "Bombe" (the Enigma-cracking machine) and mentored younger mathematicians. He knew that the search for new techniques was a "human community" effort.

👉 See also: When Was the Vacuum Invented: What Most People Get Wrong About Suction

A Quick Reality Check on the Math

It’s easy to get lost in the hype, but we should be clear about what Turing didn't do. He didn't invent the "first" computer in a vacuum. People like Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace had the spark a century earlier.

What Turing did was provide the mathematical proof that these machines were possible and limited. He gave us the "physics" of the digital world.

Why This Still Matters in 2026

If you're working in tech, or even just using it, Turing’s fingerprints are on everything.

- AI and the Turing Test. He asked, "Can machines think?" but he didn't care about "consciousness." He cared about behavior. If a machine acts intelligent, does the "internal" stuff even matter?

- Cryptography. Modern encryption (the stuff keeping your bank account safe) is the direct descendant of the statistical work he did to crack Naval Enigma. He pioneered Bayesian inference—a way of using probability to update your "guess" as you get more data.

- Generative Design. Those cool, organic-looking 3D-printed chairs? They often use Turing’s morphogenesis math to grow their shapes.

Actionable Next Steps

To really get a feel for how Turing changed the world, you don't need a PhD. You just need a bit of curiosity.

- Try a Simulator. Search for a "Universal Turing Machine simulator" online. You can actually "code" on a virtual strip of tape. It's frustratingly simple, which is exactly the point.

- Look for Patterns. Next time you see a seashell or a leaf, look at the symmetry. Read up on "Reaction-Diffusion" systems to see how math literally grows into life.

- Read the Source. If you're feeling brave, find a PDF of On Computable Numbers. Most of it is dense logic, but the introduction is surprisingly readable and shows exactly how his mind worked.

Turing wasn't just a war hero. He was the architect of the reality we live in now. Every time you open an app, you're interacting with a 90-year-old math problem that he was the first to solve.