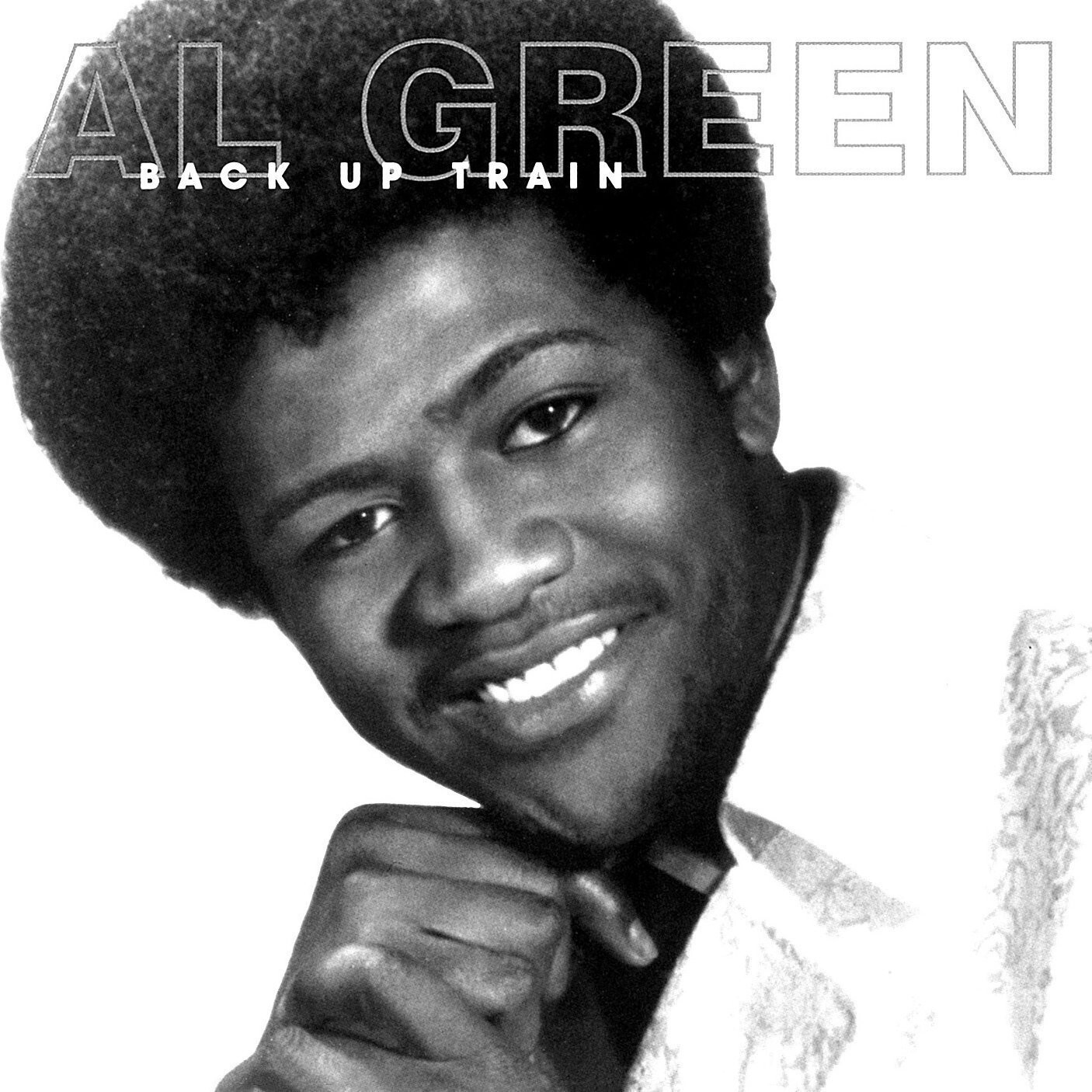

Before the silk sheets, the gold records, and the "Love and Happiness" of it all, there was a skinny kid from Arkansas trying to figure out what a hit sounded like. He hadn't found the Hi Records groove yet. He didn't have Willie Mitchell whispering in his ear to stop screaming and start singing from the back of his throat. In 1967, Al Green was just a guy with a group called the Soul Mates, and Al Green Back Up the Train was the result of a frantic, gritty recording session that sounds absolutely nothing like the Reverend we know today.

It's a weird record. Honestly, if you played it for a casual fan without telling them who it was, they’d probably guess it was a lost James Brown protégé or maybe a very aggressive Jackie Wilson imitator.

The title track actually cracked the R&B charts, peaking at number five. That’s the irony. His first taste of real success came from a sound he would eventually abandon entirely. Most people think Al Green emerged fully formed from the Memphis mist in 1971, but Al Green Back Up the Train is the messy, loud, essential proof that every legend starts out by mimicking someone else.

The Sound of a Man Trying Too Hard

If you listen to Let's Stay Together, Al's voice is like velvet. It's effortless. On this 1967 debut, however, he is working for every single note. You can hear the sweat. He’s shouting. He’s growling. He’s pushing his vocal cords to the absolute limit because, at the time, that’s what soul singers did to get noticed.

The production is handled by Palmer James and Curtis Rogers. They weren't trying to create a masterpiece of subtle nuance; they were trying to get played on AM radio in the mid-60s. The result is a mix of Northern Soul energy and gritty Southern R&B that feels slightly out of time. It’s frantic. It’s heavy on the brass. It’s got these driving, Four Tops-style rhythms that feel like a freight train—pun intended—running down the tracks.

"Back Up the Train" itself is a plea for a lover to return, a classic trope, but the delivery is so jagged. He sounds desperate. It lacks the cool, detached confidence of his later work. But man, the energy is infectious. It’s the sound of a 21-year-old who knows he’s got "it" but hasn't quite learned how to aim it yet.

A Track-by-Track Identity Crisis

The album is a fascinating document of a genre in transition. You have songs like "Hot Wire," which feels like a direct response to the "Shotgun" era of Junior Walker & the All Stars. Then you have "Don't Hurt Me No More," where Al tries on a more refined, orchestral soul coat that doesn't quite fit.

✨ Don't miss: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

It's not a cohesive album in the way I'm Still in Love with You is. It's more like a collection of singles and experiments. One minute he's a blues shouter; the next, he's trying to be a pop crooner. This lack of direction is exactly why the album is so valuable to historians and die-hard fans. It captures the "before" photo.

Why "Back Up the Train" Was the Peak and the Problem

The single "Back Up the Train" was a hit, but the album failed to capitalize on it. Why? Well, the label, Hot Line Music Journal, wasn't exactly a powerhouse. They didn't have the distribution or the marketing muscle of a Motown or a Stax.

More importantly, the industry was changing. By the late 60s, the raw, frantic soul of the early decade was giving way to something more psychedelic, more political, and eventually, more polished. Al was stuck in a 1965 sound in a 1967 world.

- The drumming is stiff compared to the later work of Al Jackson Jr.

- The horn arrangements are bright and brittle.

- The songwriting is standard-issue "love gone wrong" material without the poetic depth Al would later bring to his own lyrics.

When the album flopped commercially, Al was left adrift. He spent a few years playing small clubs, essentially becoming a journeyman singer. It’s a period of his life that gets glossed over in documentaries, but it’s where he learned the stagecraft that would make him a superstar. He had to learn how to command a room that didn't necessarily want to hear him.

The Memphis Meeting That Changed Everything

You can't talk about Al Green Back Up the Train without talking about what happened next. In 1969, Al was performing in a club in Midland, Texas. He was broke. He needed a ride. Enter Willie Mitchell, the bandleader and producer for Hi Records.

Legend has it Mitchell heard Al sing and told him, "You could be a star, but you gotta stop screaming."

🔗 Read more: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Al didn't believe him at first. He thought the screaming was the whole point. But he was hungry enough to follow Mitchell back to Memphis. That transition—from the gritty, straining vocalist of the Back Up the Train era to the silky-smooth icon of the 70s—is one of the most successful rebrandings in music history. Mitchell stripped away the artifice. He told Al to sing softly, almost in a whisper, and let the microphone do the work.

If you compare the title track of his debut to "Tired of Being Alone," the difference is staggering. It’s the difference between a hurricane and a summer breeze.

Is the Album Actually Good?

Let's be real. If this wasn't Al Green, would we still listen to it? Probably not. It would be a footnote in a "100 Forgotten Soul Gems" listicle. But because it is Al Green, every flaw becomes a fascinating insight.

There are moments of genuine brilliance. "A Lover's Hideaway" shows flashes of the melodic sensibility that would define his career. His phrasing, even when he’s shouting, has a rhythmic complexity that most of his contemporaries couldn't touch. He was already playing with the beat, sliding behind it and jumping ahead of it in a way that felt jazz-influenced.

The album is also remarkably "clean" for the era. The recordings are sharp, even if the arrangements are dated. It's a high-quality production for a small label, which suggests that everyone involved knew Al was something special, even if they weren't sure what to do with him.

The Misconception of the "Lost" Album

Some collectors treat Al Green Back Up the Train like a lost holy grail. In reality, it was re-released many times under different titles after Al became famous. You’ll see it as The Soul of Al Green or The Early Years. Don't be fooled; it's almost always the same set of recordings from that 1967 period.

💡 You might also like: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

The original pressing on Hot Line is the one that fetches the big bucks. It’s a piece of history. It represents the last gasp of a specific type of soul music before the world turned toward funk and disco.

How to Listen to It Today

If you’re a fan of the "Green is Blues" era, you’ll find a lot to love here. It’s the bridge between his gospel roots and his R&B future. To get the most out of it, don't look for the "Love and Happiness" vibe. Instead, look for:

- The Gospel Inflections: You can hear the church in his growls. He hadn't quite "secularized" his delivery yet.

- The Straining High Notes: He hits notes on this album that he would eventually reach with a falsetto, but here, he's using his full chest voice. It's physically impressive.

- The Rhythmic Tension: Pay attention to how he interacts with the brass section. He treats his voice like a trumpet.

The Legacy of the Train

Ultimately, Al Green Back Up the Train serves as a reminder that greatness isn't accidental. It’s practiced. Al had to fail—or at least, fail to reach the stratosphere—with this sound before he could find the one that resonated with the world.

It’s a gritty, loud, imperfect record. It’s the sound of a man finding his feet. And while it might not be the music you put on for a romantic dinner, it’s the music you put on when you want to hear the raw power of one of the greatest vocalists to ever walk the earth.

Practical Next Steps for Collectors and Fans

If you want to dive deeper into this specific era of Al Green's career, there are a few things you should do to ensure you're getting the real story and the best audio quality.

- Check the Credits: Ensure any compilation you buy actually features the 1967 Hot Line sessions. Many "Early Years" albums mix these with 1969-1970 Hi Records demos, which are a different vibe entirely.

- Compare the Vocals: Play "Back Up the Train" back-to-back with "I'm a Ram." You’ll hear the exact moment where the "shouting" style started to blend with the "Memphis" groove. It's a masterclass in vocal evolution.

- Hunt for Vinyl: If you're a vinyl enthusiast, look for the Bell Records distribution of the Hot Line material. It tends to have a slightly better master than the later budget-bin reissues from the 80s.

- Study the Lyrics: While mostly standard soul fare, the songwriting by Palmer James is worth a look. He was trying to bridge the gap between Detroit pop-soul and Southern grit, which was a very specific (and short-lived) subgenre.

By understanding where Al Green started, you gain a much deeper appreciation for the restraint he showed later. He didn't sing softly because he couldn't sing loudly; he sang softly because he realized that power is more effective when it's held back. That's the lesson of the train. It had to run its course so the man could eventually learn how to fly.