Al Davis didn’t just play the game. He owned the game, coached the game, and, when he felt like it, he sued the living daylights out of the people who ran it. If you grew up watching football in the '80s or '90s, you knew the Silver and Black wasn’t just a team. It was a middle finger to the establishment.

The saga of Al Davis vs the NFL isn't some dry legal footnote. It’s a decades-long blood feud between a Brooklyn-born maverick in white jumpsuits and the polished, corporate suits of Park Avenue. Most people think it was just about moving a team from Oakland to LA. Honestly? It was way more personal than that.

The Grudge That Started It All

To understand why Davis spent half his life in a courtroom, you have to go back to 1966. Davis was the Commissioner of the American Football League (AFL). He was a shark. He was actively poaching NFL stars, trying to win an all-out war between the two leagues.

Then, his own owners went behind his back.

Lamar Hunt and the other AFL bigwigs negotiated a merger with the NFL without telling Davis. They chose peace; Al wanted conquest. When the dust settled, Pete Rozelle—the NFL's golden boy—was the one running the show. Davis was relegated back to just being an owner. He never forgot it. He spent the next forty years making sure the NFL knew he was still the smartest guy in the room.

Al Davis vs the NFL: The 1980 Antitrust War

The real fireworks started when Davis decided Oakland wasn't good enough anymore. The Oakland Coliseum was aging, and Davis wanted luxury suites. He wanted a better deal. When Oakland wouldn't budge, he looked south to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

The NFL said no.

The league had a rule—Rule 4.3—that required three-quarters of the owners to approve any team move. In March 1980, the owners voted 22-0 against Davis. They thought they had him trapped. They were wrong.

Davis didn't just pack his bags; he filed a massive antitrust lawsuit. He argued that the NFL was a collection of independent businesses, not a single entity, and therefore they couldn't legally conspire to stop him from moving his business to a new market.

The Courtroom Drama

The first trial in 1981 ended in a hung jury. It was a mess. But the second trial in 1982 changed everything. The jury came back in favor of Davis and the L.A. Coliseum. They found that the NFL’s relocation rules violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.

- The Verdict: The court awarded the Raiders $11.55 million and the L.A. Coliseum $4.86 million.

- The Treble: Because it was an antitrust case, those damages were tripled.

- The Result: Davis moved the Raiders to Los Angeles for the 1982 season.

While this was happening, Davis's team was actually winning on the field. They won Super Bowl XV while the lawsuit was still active. Imagine your boss trying to fire you while you’re winning "Employee of the Year." That was the Raiders.

Why the NFL Hated the Move

Pete Rozelle and the other owners weren't just being petty (though they were definitely being petty). They were terrified of the precedent. If Davis could move whenever he wanted, the whole league structure would collapse. Owners would start bidding wars between cities every five years.

It’s the reason why the NFL eventually fought so hard to prove they were a "single entity." If they were one big company, they couldn't "conspire" with themselves. Davis blew that defense out of the water. He paved the way for the modern era of franchise relocation. Every time you see a team like the Rams or Chargers move today, you're seeing the ghost of Al Davis's legal team at work.

The Los Angeles Fallout and the Return to Oakland

The stay in LA wasn't the permanent paradise Davis imagined. By the early '90s, the L.A. Coliseum was falling apart. It didn't have the luxury boxes that drive modern NFL revenue. Davis tried to get a new stadium in Inglewood—the Hollywood Park site—but the deal went south.

Davis blamed the NFL. Again.

He claimed the league sabotaged his Inglewood stadium plans by making unreasonable demands, like forcing him to share the stadium with a second team. He eventually tucked his tail (slightly) and moved the Raiders back to Oakland in 1995.

But he didn't stop suing.

He filed a $1.2 billion lawsuit claiming the NFL still owed him for the "rights" to the Los Angeles market. He argued that since he won the right to LA in the '80s, the league couldn't let anyone else play there without paying him. This time, the luck ran out. The courts eventually tossed it, but it took years. By the time it was over, Davis had spent more time with lawyers than with his own coaching staff.

The USFL Betrayal

If you want to know how much Davis loathed his fellow owners, look at the USFL. In 1986, the upstart United States Football League sued the NFL for being a monopoly.

Every single NFL owner stood united against the threat. Except one.

✨ Don't miss: Why Pacers OKC Game 2 Flipped the Script of the 2025 NBA Finals

Al Davis showed up as a witness for the USFL. He sat on the stand and basically told the world that the NFL was a big, bad monopoly that crushed competition. He didn't care if it hurt his own bottom line; he just wanted to see the league office bleed. It was the ultimate "burn it all down" move.

Legacy of the Maverick

You’ve got to respect the sheer audacity. Davis was a pioneer in ways that had nothing to do with lawsuits. He hired the first Black head coach of the modern era (Art Shell). He hired the first Latino head coach (Tom Flores). He made Amy Trask the first female CEO of an NFL team.

He was a civil rights leader who refused to let his team play in cities with segregated hotels. He was a brilliant scout who revolutionized the vertical passing game. But the Al Davis vs the NFL narrative is what defines his public image because it represents a specific American archetype: the man who refuses to be told "no."

What We Can Learn from the Davis Wars

- Markets are never settled. Davis proved that no team "belongs" to a city in the eyes of the law; they are businesses looking for the best deal.

- Antitrust is the NFL's Achilles heel. The league still operates in a grey area, constantly lobbying Congress to protect its "single entity" status so they don't face another Al Davis.

- Conflict can be a brand. The Raiders became the "bad boys" of sports specifically because their owner was always in a street fight with the commissioner.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Historians

If you're trying to understand the modern NFL landscape, don't just look at the highlights. Look at the court filings.

- Research the "Single Entity" Defense: Look up American Needle, Inc. v. National Football League. It’s the spiritual successor to the Davis lawsuits and explains why the NFL still worries about antitrust.

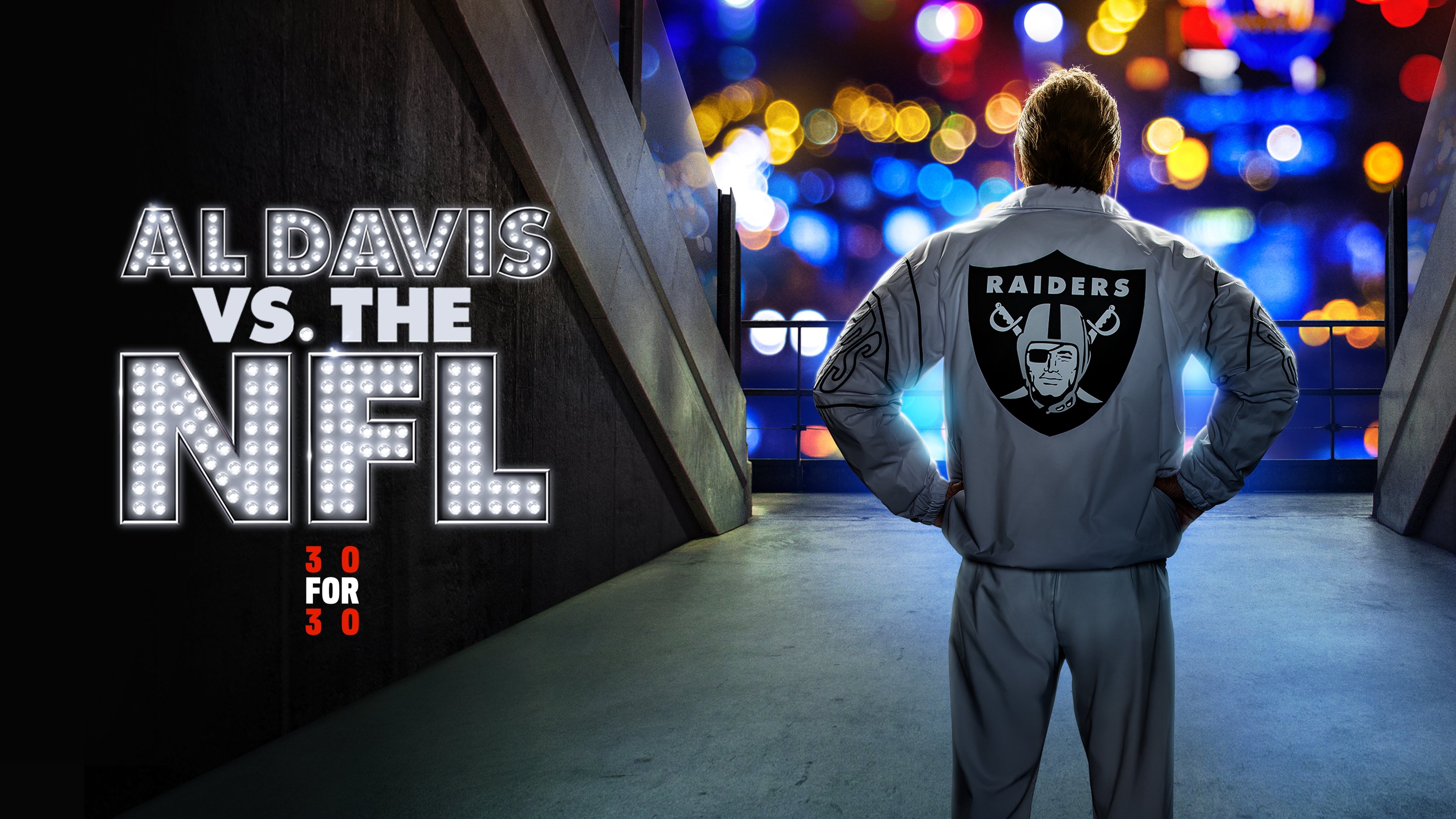

- Watch the 30 for 30: ESPN’s Al Davis vs. The NFL uses "deepfake" technology to have Davis and Rozelle "talk" to each other from beyond the grave. It's weird, but it captures the bitterness perfectly.

- Follow the Money: Understand that stadium subsidies today exist because Al Davis proved owners can leave. If a city won't pay for a stadium, the "Davis Precedent" says the team can find a city that will.

The war ended in 2011 when Al Davis passed away. His son, Mark Davis, eventually got the deal his father always wanted: a state-of-the-art stadium in Las Vegas, mostly paid for by someone else. In a weird way, Al finally won. He just wasn't around to see the kickoff.