The roar of a thousand Merlins isn't something you just forget. Honestly, when we think about the air war in the 1940s, we usually jump straight to Top Gun style dogfights or those grainy clips of Spitfires chasing Messerschmitts over the white cliffs of Dover. It’s cinematic. It’s visceral. But the reality of air World War 2 was actually a lot more about math, cold weather, and sheer industrial exhaustion than it was about heroic duels in the clouds.

The sky was a meat grinder.

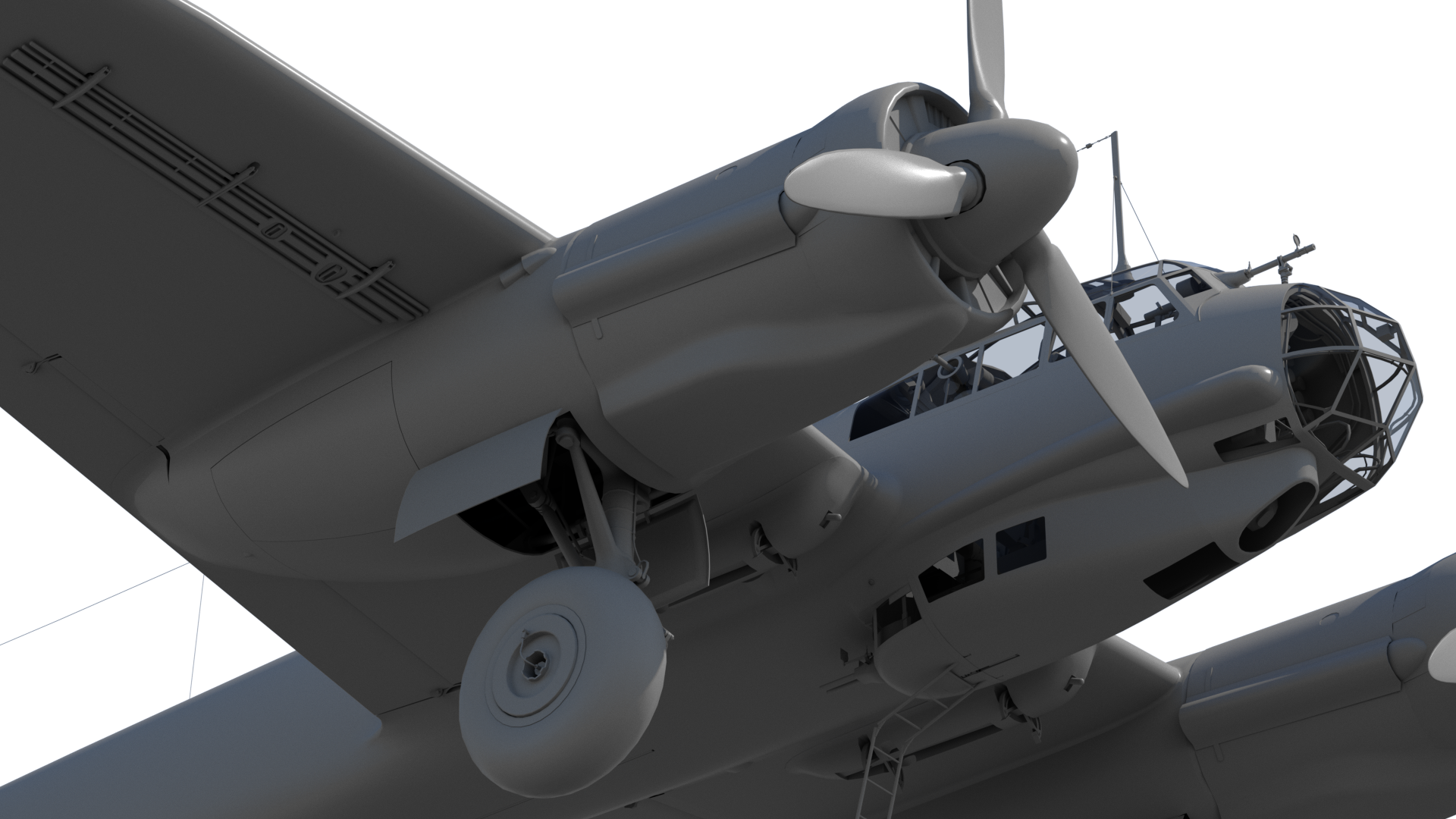

Most people don't realize that being in the Eighth Air Force was statistically more dangerous than being a Marine on Iwo Jima. You had a better chance of surviving a tour of duty in the literal trenches of the Great War than you did finishing twenty-five missions in a B-17 Flying Fortress during the early years. We're talking about teenagers flying unpressurized tin cans at 25,000 feet where the temperature dropped to -50 degrees. If you touched the metal with your bare skin, it would instantly fuse. You’d lose the skin. Maybe the finger.

The Myth of the Precision Strike

We hear a lot about "precision bombing." It's a term that gets thrown around in modern news, but back then? It was basically a polite fiction. The Norden bombsight was supposed to be able to "drop a bomb into a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet," or so the propaganda claimed. In the real world of air World War 2, if a bomb landed within a thousand feet of the target, the crew considered it a direct hit. High-altitude winds, thick European cloud cover, and the sheer terror of flak made "precision" impossible.

Take the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission in 1943. The goal was to wipe out ball-bearing plants. Why ball bearings? Because everything that moves needs them. If you stop the bearings, you stop the Panzers. Simple, right? Except the US Army Air Forces lost 60 bombers in a single day. That’s 600 men gone, captured, or dead. And the Germans? They just bought bearings from Sweden.

This is the nuance people miss. The air war wasn't just about blowing stuff up; it was an economic chess match played with human lives. You weren't just fighting pilots; you were fighting the guy in the factory in Essen and the girl assembling fuses in Birmingham.

📖 Related: Typhoon Tip and the Largest Hurricane on Record: Why Size Actually Matters

Technology that Changed the Game (And Why it Almost Failed)

If you’ve ever looked at a P-51 Mustang, you’re looking at arguably the most important machine of the 20th century. But here’s the kicker: it was a flop at first. When it first flew with an American Allison engine, it was mediocre at high altitudes. It wasn't until someone had the bright idea to shove a British Rolls-Royce Merlin engine into it—the same heart that powered the Spitfire—that it became the "Cadillac of the Skies."

Suddenly, American bombers had "Little Friends" that could fly all the way to Berlin and back. Before the Mustang, the bombers were essentially sitting ducks once their short-range escorts had to turn back for fuel.

Imagine being a B-17 pilot. You see your escort fighters wave goodbye over the German border because their fuel needles are hitting red. You know that for the next three hours, you are completely alone. Then, in 1944, the Mustangs don't turn back. They stay. That shift in technology changed the entire outcome of the war. It allowed the Allies to achieve "Air Supremacy," which is a fancy way of saying the Luftwaffe basically stopped existing as a functional force.

The Logistics of Death

We talk about the "aces"—the guys like Erich Hartmann with 352 kills or Chuck Yeager. But the real story of air World War 2 is found in the logistics. It's about the Liberty Ships hauling millions of gallons of high-octane aviation fuel across an ocean infested with U-boats.

The Soviet Union’s contribution is often sidelined in Western textbooks too. While the US and UK were focused on strategic bombing (hitting factories), the Red Army’s air force, the VVS, was doing "Sturmovik" work. The Il-2 Sturmovik was a flying tank. It flew so low the pilots could see the expressions on the faces of the German soldiers they were strafing. Stalin famously said the Il-2 was as "essential as bread" to the Red Army. They built over 36,000 of them. That’s more than any other combat aircraft in history.

👉 See also: Melissa Calhoun Satellite High Teacher Dismissal: What Really Happened

Think about that number for a second. 36,000.

The Night Terrors: RAF Bomber Command

While the Americans flew by day, the British flew by night. This wasn't because they were "braver" or "stealthier"—it was because their early daylight raids were so disastrous they realized they’d be wiped out if they kept it up.

Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris, the head of Bomber Command, had a very different philosophy than the Americans. He didn't care about "pickle barrels." He practiced "area bombing." The goal was to dehouse the German worker. It sounds clinical. It was actually horrific.

The firestorm in Dresden or the raids on Hamburg turned cities into ovens. The physics are terrifying: the fire gets so hot it sucks all the oxygen out of the air, creating a vacuum that pulls people into the flames. Aircrews flying miles above could smell the burning wood and... other things. Many of these young men, barely twenty years old, struggled with the morality of what they were doing, even as they knew it was necessary to stop the Nazi machine.

What People Get Wrong About the Flak

In movies, flak is just little black puffs of smoke. In reality, flak was 88mm shells screaming into the air and exploding into jagged shards of hot steel. It didn't have to hit the plane. It just had to explode near it.

✨ Don't miss: Wisconsin Judicial Elections 2025: Why This Race Broke Every Record

Airmen wore "flak suits"—heavy, cumbersome vests lined with manganese steel plates. They were hot, they were heavy, and they didn't always work. If a piece of shrapnel hit the Plexiglas nose of a bomber, it didn't just break the window; it turned the glass into secondary shrapnel.

The Psychological Toll

We didn't have a word for PTSD back then. They called it "flak happy" or "operational fatigue." If a pilot decided he couldn't fly anymore, he was often branded with "LMF"—Lack of Moral Fibre. It was a career-ending, soul-crushing designation.

You’ve got to remember the sheer sensory overload. The vibration of four massive radial engines, the chatter of .50 caliber machine guns, the smell of cordite and hydraulic fluid, and the constant, gnawing cold. Then, total silence when the engines cut out over the English Channel. The transition from high-stakes survival to having a pint in a quiet village pub in East Anglia within the span of two hours was enough to break anyone’s mind.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to actually understand the air World War 2 experience beyond the Hollywood tropes, you need to look at specific primary sources and locations that keep this history alive.

- Read "Serenade to the Big Bird" by Bert Stiles. He was a B-17 pilot who wrote the most honest, least "heroic" account of the war before he was killed in action. It's raw and human.

- Visit the Imperial War Museum Duxford. If you're ever in the UK, this is the mecca. Seeing a B-24 or a Lancaster in person makes you realize how flimsy these "heavies" actually were. They feel like giant kites.

- Study the "Oil Campaign." If you want to know how the air war was actually won, research how the Allies targeted Germany's synthetic oil plants in 1944. It grounded the Luftwaffe better than any dogfight ever could.

- Check out the American Air Museum's digital archive. They have thousands of photos and personal stories from the 8th Air Force that haven't been sanitized for TV.

The air war wasn't a game of knights in the sky. It was an industrial process—a brutal, terrifying, and ultimately decisive effort that redefined how we think about distance, power, and the cost of victory. When you look up at a clear blue sky today, it’s hard to imagine it filled with 2,000 bombers and 800 fighters, all trying to kill each other. But for a few years in the 1940s, that was the only world there was.