You've heard the words everywhere. They’re on TikTok. They’re in your favorite Netflix show. They’re even popping up in corporate Slack channels where a manager is trying a little too hard to be "relatable." But here is the thing about African American slang—most of the time, the people using it have no idea where it actually comes from or what it really signifies.

It isn't just a collection of "cool" words. It's a linguistic system.

Honestly, calling it "slang" is a bit of a misnomer to begin with. Linguists like John Rickford or Geneva Smitherman usually refer to it as African American Vernacular English (AAVE). It has its own grammatical rules, its own tense structures, and a history that stretches back through the Great Migration all the way to the West African coast. When you hear someone say "I been knew," they aren't making a mistake. They are using a specific tense called the "remote past" that indicates something has been true for a very long time. It’s precise.

The Cultural Weight of African American Slang

Language is a survival tool. For Black Americans, it always has been. During the era of chattel slavery, coded language was a way to communicate without being understood by overseers. This tradition of "signifying" or "double-voicedness" stayed in the DNA of the dialect. It’s about more than just sounding hip; it’s about community identity.

One of the biggest misconceptions is that this way of speaking is just "internet slang" or "Gen Z lingo." You see this all the time on Twitter. Someone uses the word "cap" or "bet," and suddenly a million people think it was invented by a teenager in a bedroom in 2021. In reality, a lot of these terms have been circulating in Black neighborhoods in Atlanta, Chicago, and Detroit for decades.

It’s about ownership.

When a word moves from a specific subculture into the mainstream, it often loses its original nuance. Take the word "woke," for instance. Before it became a political lightning rod used by pundits, it was a phrase used in the Black community (think Lead Belly in the 1930s) to literally mean staying aware of social and racial injustice. Now? The original meaning has been almost entirely swallowed by its use as a pejorative.

Why We Struggle to Define AAVE

The rules of African American slang are incredibly complex, even if they feel intuitive to native speakers.

Consider the "habitual be." If I say, "He be working," I’m not saying he is working right now. I’m saying he has a job and he goes to it regularly. If I say, "He working," that means he is currently at his desk. It’s a distinction that standard English doesn't make as efficiently.

This isn't "broken English." It’s a dialect with a consistent logic.

However, the mainstream often views it through a lens of "correctness" versus "incorrectness." This creates a dynamic called code-switching. Many Black professionals spend their entire day toggling between two different versions of themselves—one that adheres to the rigid structures of Corporate English and another that feels like home. It’s exhausting. It’s a mental tax that people who only speak the dominant dialect never have to pay.

The Influence of Music and Social Media

We can't talk about the spread of these terms without mentioning Hip-Hop. It’s the primary engine of global culture right now. When a rapper in Atlanta drops a new track, the vocabulary in that song can be in London or Tokyo within 48 hours.

But there’s a flip side.

🔗 Read more: That Annoying Rattle: Dealing With a Loose Heat Shield Car Problem Without Getting Ripped Off

The "digital blackface" phenomenon is real. It happens when non-Black creators adopt the cadence, vocabulary, and mannerisms of AAVE to appear edgy or funny, often while profiting from it. They get to put the "costume" on and take it off whenever they want. They don't have to deal with the systemic biases that actual speakers face in job interviews or classrooms.

Basically, the culture is loved, but the people often aren't.

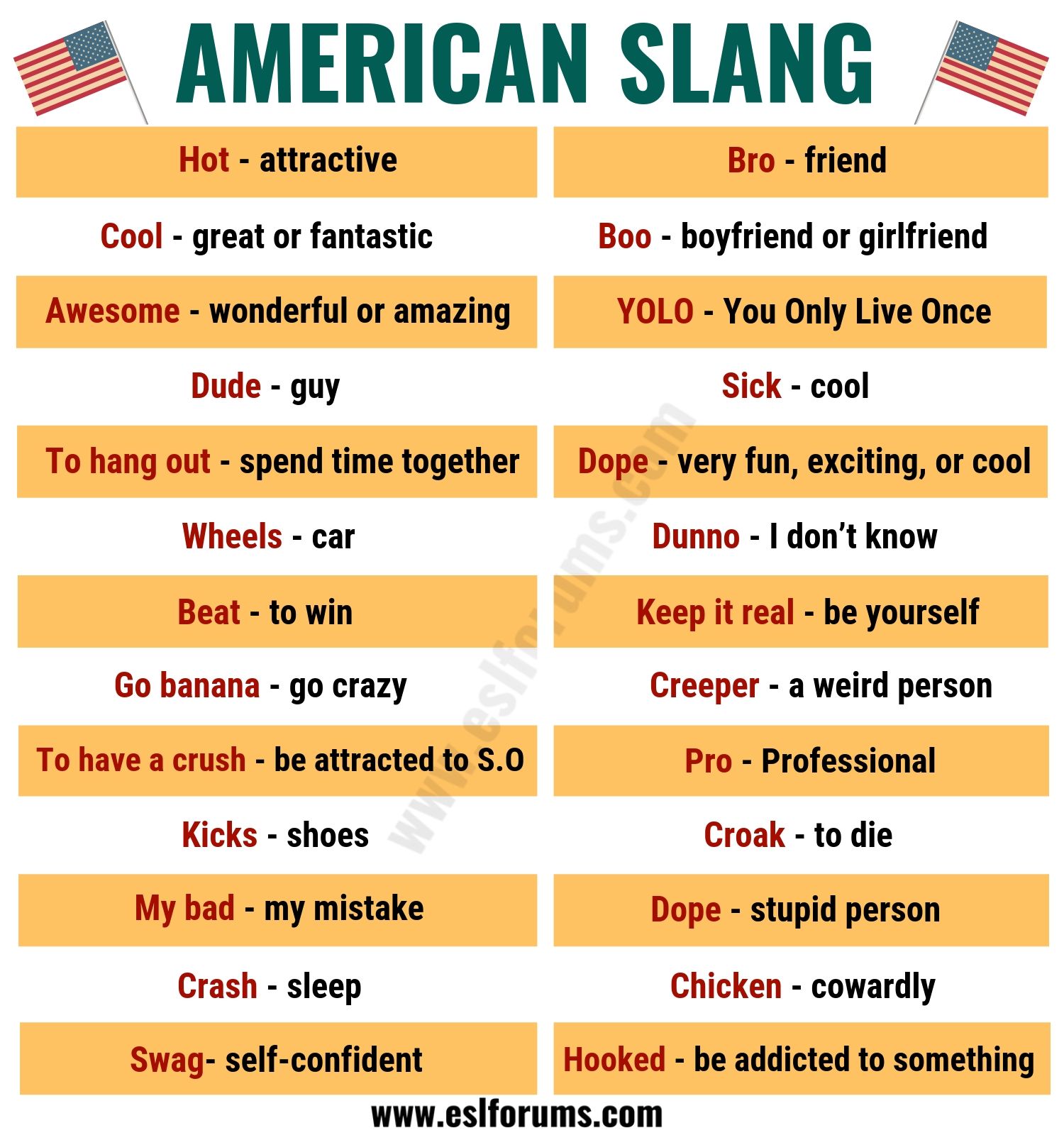

Common Words Everyone Misuses

Let's look at a few examples of African American slang that have been distorted in the public consciousness:

- Chile: People write this on the internet and think it’s just a cute way of saying "child." But in the Black community, the intonation matters. It’s often used to express exhaustion, disbelief, or to punctuate a piece of gossip.

- Periodt: Adding the 't' at the end isn't just for flair. It’s a definitive stop. It’s the vocal equivalent of a gavel slamming down.

- Tea: While "spilling the tea" is now a staple of drag culture and Gen Z, its roots are deep in Black queer circles. It refers to "T" for "Truth."

The speed at which these terms are harvested by brand marketing teams is dizzying. One day a term is a niche community identifier, and the next day it's being used by a brand of laundry detergent on Instagram. This leads to what some call "semantic bleaching"—the process where a word is used so much by people who don't understand it that it loses all its original flavor and impact.

The Academic Battle Over Language

For a long time, educators treated AAVE as a deficit. They thought kids who spoke it were simply "bad at English."

In 1996, the Oakland Ebonics controversy exploded. The school board wanted to recognize Ebonics (another term for AAVE) as a primary language for African American students so they could use specialized teaching methods to help them learn Standard English. The backlash was massive. People were outraged. They thought the school was "teaching slang."

They weren't. They were trying to bridge a linguistic gap.

Renowned linguist William Labov has spent decades proving that AAVE is a "rule-governed" system. It isn't random. It isn't lazy. It’s a legitimate linguistic structure that carries the history of a people. When we dismiss it as "slang," we’re dismissing the history and intelligence of the people who speak it.

Regional Variations You Might Not Know

Not all African American slang is the same. It changes depending on where you are.

If you're in Philly, you’re going to hear "jawn" used for literally anything—a person, a place, a sandwich, a situation. If you're in the DMV (DC, Maryland, Virginia), "moe" is the go-to. Down in New Orleans, the slang is heavily influenced by French Creole roots and a specific Southern bounce.

It’s a living, breathing thing. It evolves.

A word that was "lit" in 2016 might be "cringe" by 2026. That’s just the nature of language. But the underlying structure—the grammar and the soul of it—remains remarkably consistent across geographic lines because it’s tied to a shared cultural experience.

Navigating the Ethics of Using Slang

So, can you use it if you aren't Black?

It’s a gray area, but generally, if you have to ask, you should probably be careful. Context is everything. Using a term naturally because you grew up in a multi-ethnic environment is one thing. Forcing it because you want to sound "current" or "urban" usually ends up sounding like a caricature.

It’s about respect.

If you’re going to use the language, you should at least understand the weight it carries. You should know that for many people, speaking this way has historically been used as a reason to deny them housing, jobs, or a fair trial. Language doesn't exist in a vacuum. It’s tethered to power.

Practical Steps for Understanding and Respect

If you want to be a better communicator and a more informed observer of culture, here is how you can actually engage with African American slang without being a "colonizer" of the language:

Listen more than you speak. Don't rush to adopt the newest word you saw on a TikTok trend. Observe how it's used in its original context. Notice the tone, the timing, and the relationship between the speakers.

Educate yourself on AAVE grammar. Read books like Talkin and Testifyin by Geneva Smitherman. Understanding the "why" behind the "what" will give you a much deeper appreciation for the complexity of the dialect. It transforms it from "slang" into "heritage" in your mind.

Avoid the "Blaccent." There is nothing more uncomfortable than someone switching their vocal pitch and rhythm to mimic a Black person when they start using certain words. It’s performative. Just be yourself. If a word like "dope" is part of your natural vocabulary, cool. If you're putting on a character to say it, stop.

Acknowledge the source. When you see a new term blowing up, do a quick search. Who started it? Usually, it's a Black creator who isn't getting the credit. Giving credit where it's due is the easiest way to combat the erasure that often happens in digital spaces.

Stop calling it "Gen Z language." Correct people when they do this. It’s a small thing, but it helps preserve the history of the dialect. Most "Gen Z" slang is just Black English that finally reached the suburbs.

Language is the most human thing we have. It’s how we tell our stories. African American slang isn't just a trend; it's a testament to resilience and creativity. Treat it with the respect a centuries-old culture deserves.