History books usually treat the arrival of Europeans in Africa as a single, sudden wave of conquest. It wasn't. Long before the "Scramble for Africa" in the 1800s, there was a man named Mvemba a Nzinga, better known as Afonso I of Kongo, who sat on a throne in Mbanza Kongo and tried to manage a relationship with a superpower. He wasn't some naive bystander. He was a brilliant, frustrated, and ultimately tragic figure who saw the future coming and tried to write his way out of a nightmare.

Most people think of the transatlantic slave trade as something that just happened to passive populations. Afonso I of Kongo proves that's wrong. He was a King who converted to Christianity—not just for show, but because he genuinely believed it was the path to modernizing his empire. He learned to read and write Portuguese fluently. He built schools. He imported European masonry techniques. But his biggest legacy? A series of increasingly desperate letters to the King of Portugal, Joao III, pleading with him to stop the illegal kidnapping of his people.

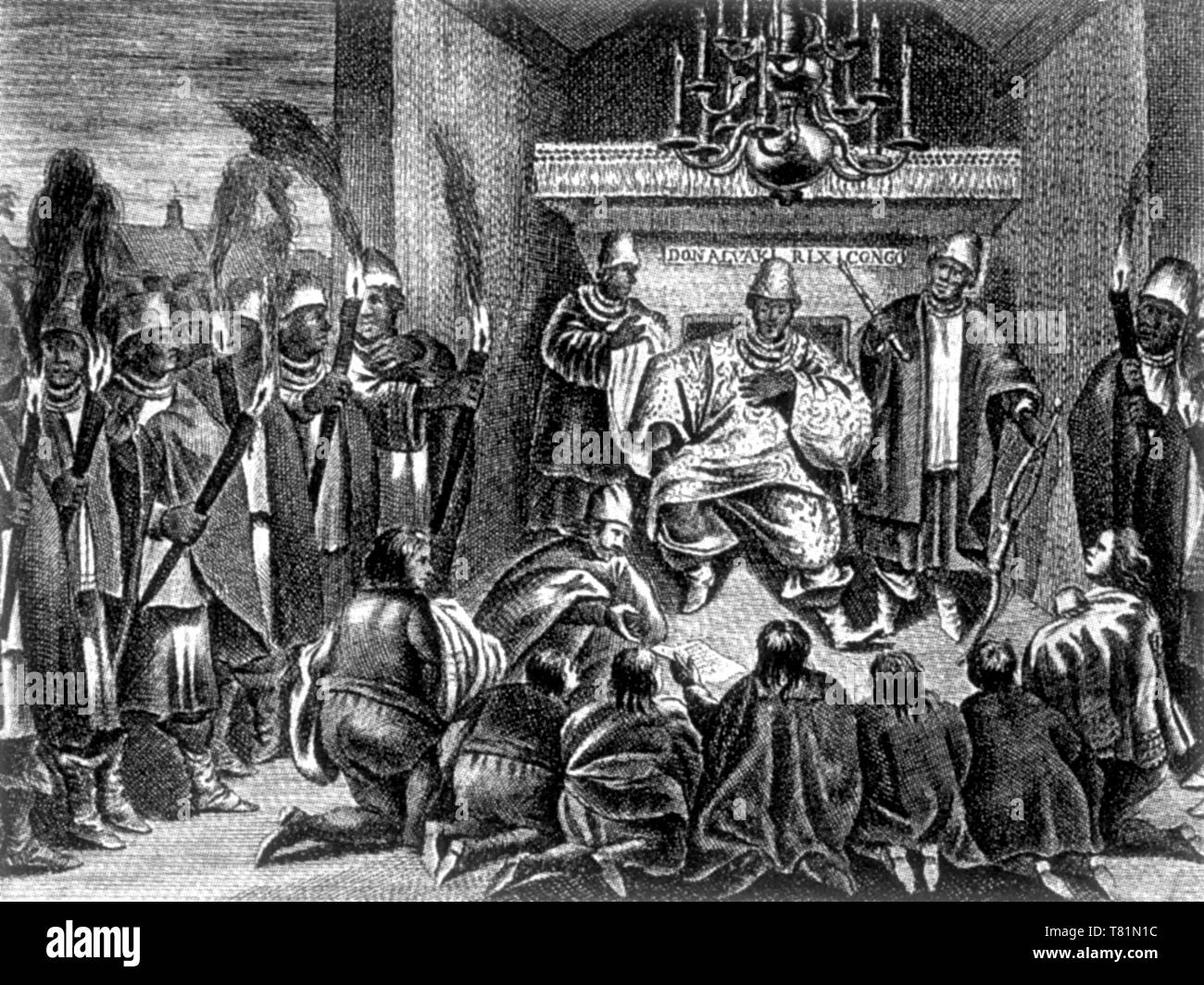

The Man Who Became Afonso I of Kongo

Before he was a Christian King, he was a prince of the Manikongo. When his father, Nzinga a Nkuwu, first met Portuguese explorers in the late 1400s, the vibe was actually... optimistic? Sort of. The Kongo Kingdom was massive, stretching across what is now northern Angola, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It was a sophisticated state with its own currency (cowrie shells), a complex tax system, and a professional army.

Afonso took the throne in 1506 after a nasty succession struggle against his brother, Mpanzu a Kitiri. Tradition says Afonso won because he had a vision of Saint James the Greater, but historians like John Thornton suggest it was more about Afonso’s tactical use of Portuguese firearms and support. He wasn't just a religious zealot; he was a pragmatist. He saw the Portuguese as a source of technology and global legitimacy. He renamed his capital São Salvador. He wanted to turn his kingdom into a "Black Portugal," an equal partner on the world stage.

He was basically trying to do what Japan did during the Meiji Restoration, but 350 years earlier. He wanted the tech without the takeover.

🔗 Read more: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

When the Partnership Turned Poisonous

For a while, it worked. Afonso sent his son, Henrique, to Lisbon to study. Henrique eventually became the first Black African bishop in the Catholic Church. This was a huge deal. It showed that Afonso was playing the long game. He wasn't just trading; he was integrating his elite class into the global intellectual community.

But then came the "merchants."

Portugal didn't want a peer; they wanted a plantation. By the 1520s, the demand for labor in the newly "discovered" Brazil was skyrocketing. The Portuguese traders on the island of São Tomé realized they could make way more money kidnapping people than they could trading for copper or ivory.

This is where Afonso I of Kongo becomes a truly modern figure. He didn't just grab a spear; he grabbed a pen. In 1526, he wrote a letter that still haunts historians today. He told the Portuguese King: "Each day the traders are kidnapping our people—children of this country, sons of our nobles and vassals, even people of our own family."

💡 You might also like: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

He complained that the Portuguese were literally emptying his country. He tried to set up a commission to inspect every person being put on a ship to ensure they weren't being stolen. It didn't work. The Portuguese merchants just bribed his officials or bypassed the capital entirely.

The Myth of the "Puppet King"

Some people look at Afonso and think he was a sell-out. They see the crucifixes and the Portuguese name and assume he was a puppet. Honestly, that's a lazy take. If you read his correspondence, you see a man who was constantly maneuvering. He banned the sale of most Kongo citizens, but he was trapped in a global economic system that he didn't create.

He needed Portuguese goods—cloth, tools, and weapons—to maintain his internal power. The Portuguese only wanted slaves. It was a vicious cycle. If Afonso stopped the trade entirely, his rivals would just trade with the Portuguese secretly, get guns, and overthrow him. He was stuck between a rock and a hard place.

He even survived an assassination attempt in 1539. Portuguese residents literally opened fire on him while he was at Mass. They missed, killing one of his courtiers instead. Imagine that. You've converted to their religion, you're speaking their language, and they try to gun you down in your own church because you're "restricting trade."

📖 Related: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

Why We Still Talk About Him in 2026

Afonso died around 1542 or 1543. After his death, the Kingdom of Kongo started a slow, painful slide into instability. But his reign remains a case study in "what if."

What if Portugal had treated Kongo as a sovereign ally?

What if the "technical assistance" Afonso asked for (physicians, shipbuilders, and teachers) had actually arrived in the quantities he requested?

Afonso I of Kongo wasn't just a king; he was a diplomat who realized, perhaps too late, that the people he invited to dinner were actually planning to steal the house. He represents the first major African resistance to the dehumanization of the slave trade—not through warfare, but through international law and moral appeal.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you want to understand the real Afonso beyond the surface-level Wikipedia summaries, you've got to look at the primary sources. History isn't just dates; it's the paper trail people leave behind.

- Read the "Letters of Afonso I": You can find translated versions of his 1526 letters in collections like The African Past by Basil Davidson. It’s wild to see how "modern" his complaints sound. He talks about corruption and "depopulation" like a 21st-century politician.

- Trace the Geography: Look at a map of the Mbanza Kongo ruins (a UNESCO World Heritage site). Seeing the physical layout of his capital helps you realize this wasn't a "primitive" settlement; it was a metropolitan hub.

- Study the Religious Syncretism: Don't just assume Kongo became "Catholic." Look at how they merged traditional Kimpasi beliefs with Christian icons. Afonso used the cross because it already looked like a Kongo symbol for the cosmos.

- Acknowledge the Complexity: Avoid the "hero or villain" binary. Afonso was an elite ruler who participated in certain forms of domestic slavery common at the time, but he fought against the industrial-scale export of his people. Holding both those truths at once is how you get to the "human" quality of history.

The story of Afonso I of Kongo is a reminder that globalization has always had a dark side, and that the pen isn't always mightier than the sword—but it does leave a much clearer record of what went wrong. For anyone looking to understand the roots of the modern Atlantic world, his letters are required reading.