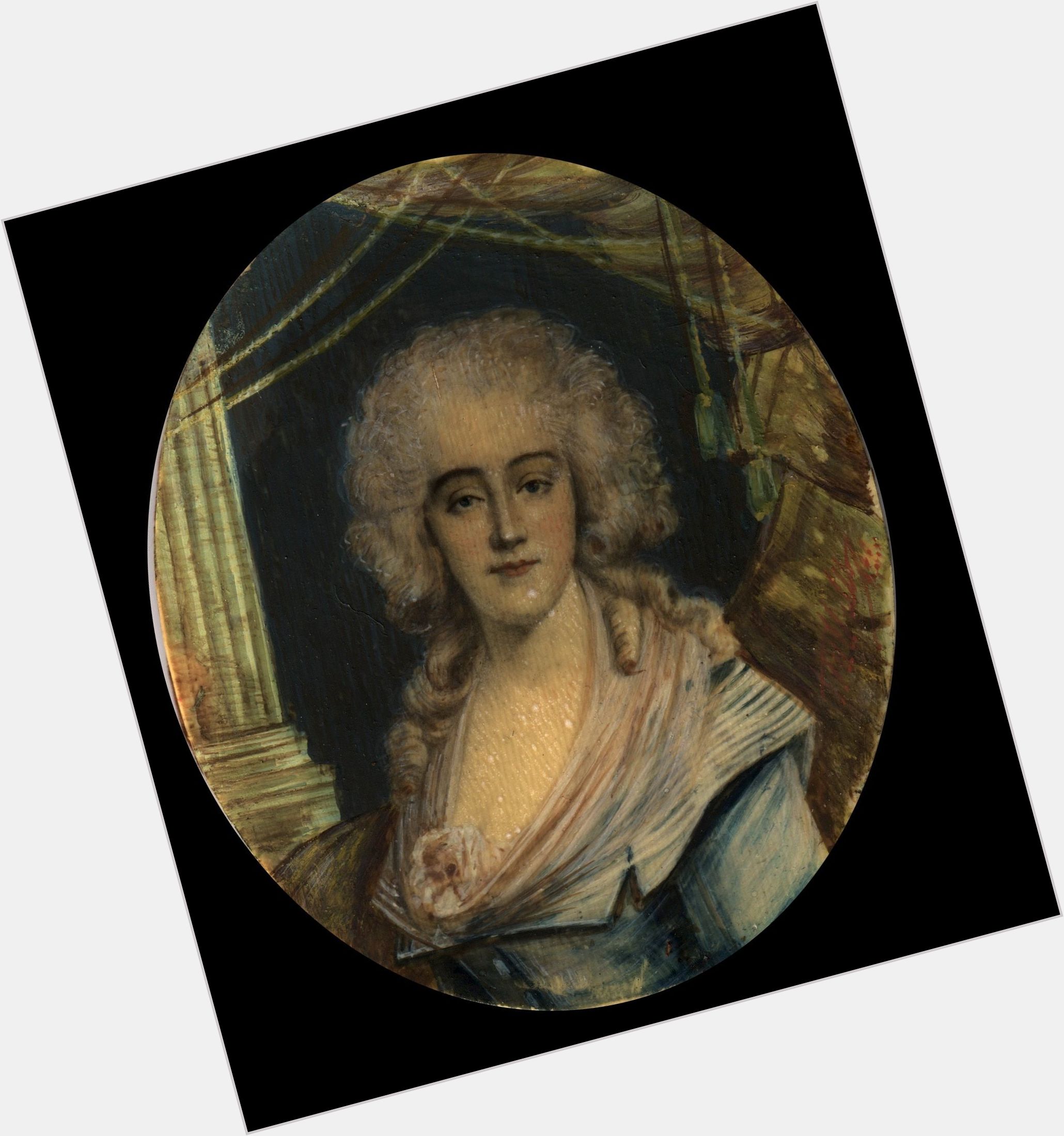

You’ve heard of the Marquis de Lafayette. He’s the "Hero of Two Worlds," the guy who basically funded a chunk of the American Revolution and became George Washington’s favorite adopted son. But history usually treats his wife, Adrienne de La Fayette, like a background character in a period drama. She’s the woman who stayed home, right? The one who waited patiently while her husband chased glory across the Atlantic?

Honestly, that’s just wrong.

Adrienne was more than a supportive spouse. She was a political powerhouse, a survivor of the Reign of Terror, and quite possibly the only reason the Lafayette name didn't end with a guillotine blade in 1794. If you think the Marquis had it rough in an Austrian prison, you haven't seen what Adrienne went through in the streets of Paris.

A Marriage of (In)convenience

It started as a business deal. In 1774, Adrienne de Noailles was only fourteen. Gilbert—that’s the Marquis—was sixteen. They were two of the wealthiest teenagers in France, and their marriage was orchestrated by the powerful Noailles family to consolidate land and influence.

Most people expect this to be a cold, formal arrangement. It wasn't. They actually fell in love. But it wasn't an easy love. Two years into the marriage, Gilbert decided to run off to America without telling her. He didn't just go for a trip; he bought a ship and sailed away to fight a war, leaving a pregnant Adrienne to deal with the fallout from the French King and her incredibly pissed-off father.

She didn't crumble. She defended him. While he was busy at Valley Forge, she was managing their estate and navigating the treacherous waters of the French court.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

The Experiment in Freedom

Here’s something the history books often skip: Adrienne and Gilbert were early, radical abolitionists. They didn't just talk about "liberty" in a vague, philosophical sense. They actually bought two slave plantations in Cayenne (French Guiana) in the 1780s.

The goal?

Basically, it was a pilot program for emancipation. They wanted to prove that you could transition enslaved people to freedom through education and fair wages. While Gilbert was back in France playing politics, Adrienne was the one managing the details. She banned flogging. She set up schools on the plantations. She was trying to build a blueprint for a world without slavery, a project that was unfortunately cut short by the chaos of the French Revolution.

Surviving the Terror

When the French Revolution hit, things got dark. Fast. Because Adrienne was a Noailles—one of the top-tier aristocratic families—she was a walking target for the radicals.

By 1792, her husband had fled France and was captured by the Austrians. Adrienne was left alone. In 1794, during the height of the Reign of Terror, she watched as the revolutionary government arrested her grandmother, her mother, and her sister. All three were guillotined on the same day.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Adrienne was next.

She was sitting in a cell, waiting for her name to be called for the "national razor." She was saved by an unlikely duo: James and Elizabeth Monroe. Elizabeth Monroe actually visited Adrienne in prison, a move that signaled to the French government that executing her would destroy their relationship with the United States. It worked. Adrienne was released in 1795, but she didn't head for safety.

The Woman Who Chose Prison

Most people, after escaping execution, would run. Adrienne went to Vienna. She petitioned the Austrian Emperor for a weird request: she wanted to be imprisoned with her husband.

She took her two daughters, Anastasie and Virginie, and moved into a damp, dark cell in the Olmütz fortress. They lived there for nearly two years. The conditions were horrific. No fresh air, terrible food, and constant sickness. Adrienne’s health never truly recovered from those years in the dark.

Why did she do it?

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

It wasn't just "wifely duty." It was a political statement. By being there, she made it impossible for the world to forget about the Marquis. She turned him from a forgotten prisoner into a symbol of suppressed liberty.

The Quiet Power of La Grange

After their release in 1797, Adrienne became the family’s legal and financial fixer. The Revolution had stripped them of almost everything. She spent years fighting in court to reclaim her family’s properties, eventually securing the Chateau de La Grange.

She was the one who kept the lights on. She managed the accounts, handled the creditors, and made sure their children had a future. She did all of this while suffering from a chronic, mysterious illness—likely a result of the lead poisoning or infections she picked up in prison.

She died on Christmas Eve in 1807 at the age of 48. Her last words to her husband were, "Je suis toute à vous" (I am all yours). But looking at her life, it’s clear she belonged to no one but herself.

Actionable Insights from the Life of Adrienne de La Fayette

If you're looking to understand the real history behind the "founding mothers" of the Atlantic world, start here:

- Look Beyond the Correspondence: While the Marquis’s letters are famous, Adrienne’s actions—managing plantations, negotiating with Emperors, and surviving the Terror—show a woman who exercised agency in a world that tried to strip it from her.

- Study the Cayenne Project: Research the "La Belle Gabrielle" plantation. It’s a vital, often overlooked piece of the anti-slavery movement that predates many better-known efforts.

- Visit Picpus Cemetery: If you're ever in Paris, skip the tourist traps and go to the Picpus Cemetery. Adrienne and Gilbert are buried there, near the mass grave of the 1,306 people guillotined during the Terror, including her own mother and sister. It is a sobering reminder of the price she paid for her family's survival.

- Read the Memoirs: Adrienne wrote a biography of her mother while she was struggling with her own health. It provides a rare, first-hand look at the internal life of the French nobility during their collapse.

Adrienne de La Fayette wasn't just a wife. She was the anchor. Without her, the "Hero of Two Worlds" likely would have died as a footnote in an Austrian dungeon.