Frankly, most people who look into military history end up finding Adrian Carton de Wiart and thinking he's a fictional character. He isn't. But his life reads like a rejected Hollywood script because it’s just too "on the nose." He was a one-eyed, one-handed Belgian-born British officer who fought in the Boer War, World War I, and World War II. He was shot in the face, head, stomach, ankle, leg, hip, and ear. He survived two plane crashes. He tunneled out of a POW camp.

And he wrote in his memoirs: "Frankly, I had enjoyed the war."

That’s not a typo. He enjoyed it. While most soldiers were understandably traumatized by the industrial-scale slaughter of the 20th century, Carton de Wiart seemed to find his zen in the middle of a barrage. He didn't care about politics much. He didn't care for the "brass" or the paperwork. He just wanted to be where the action was. This isn't just a story about a "tough guy"—it’s a weird, deep look into a specific type of human psyche that barely exists anymore.

The Boer War: Where the Madness Started

He started his career by lying. In 1899, he dropped out of Oxford, ditched his real name, and pretended to be 25 so he could enlist and fight in South Africa. He was actually 20. His father was furious, obviously. But by the time the old man found out, Adrian had already been shot in the stomach and the groin and sent back to England.

Most people would take that as a sign to maybe try law or accounting. Not this guy.

He went back as soon as he could. He eventually joined the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards. It’s worth noting that he was basically a nomad of war. He didn't really have a "home" in the traditional sense; his home was the front line. He spent the years between the big wars hunting and socialising, but you can tell from his letters and the way he carried himself that he was just waiting for the next big blow-up.

World War I and the Somme

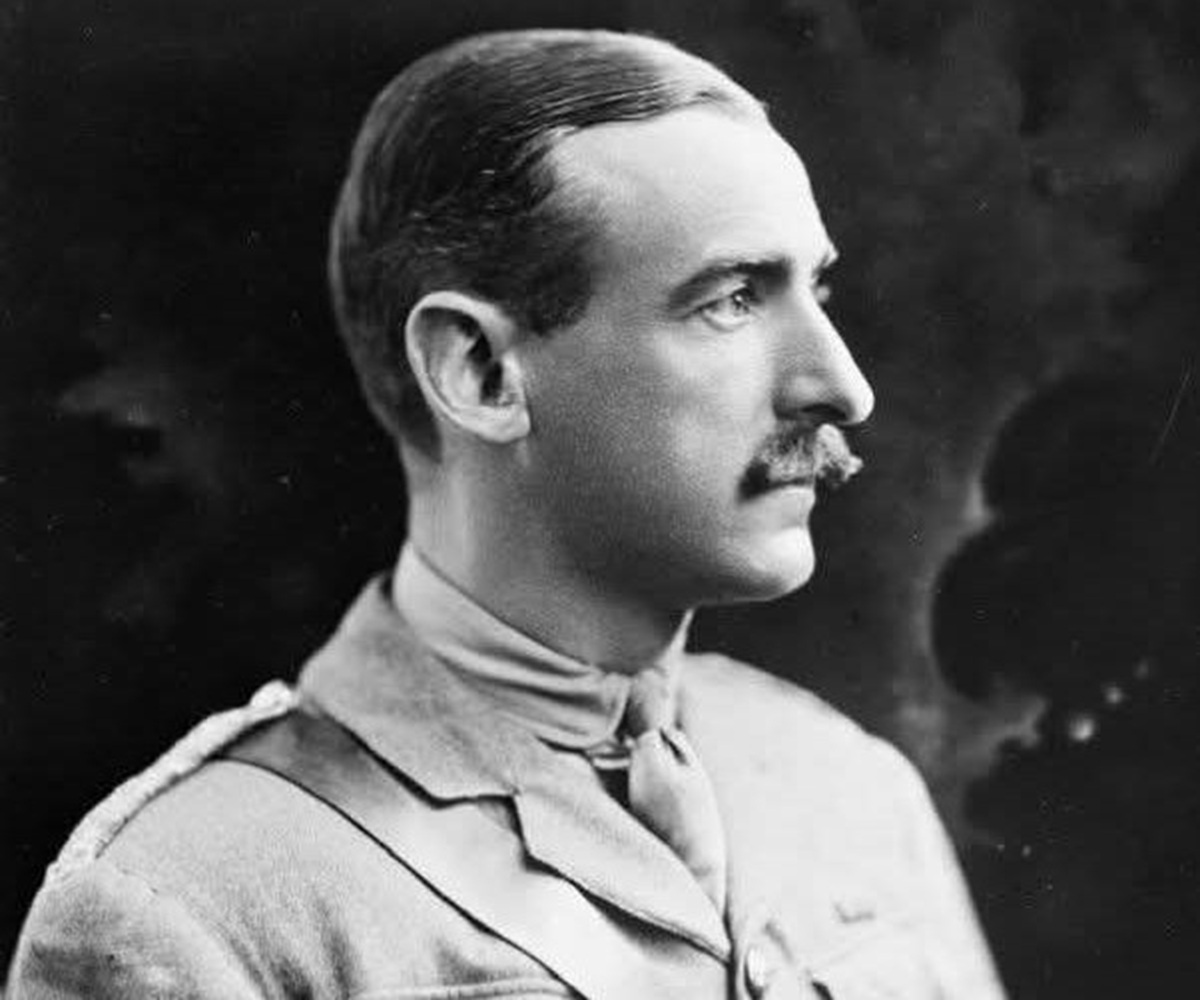

When 1914 rolled around, Adrian Carton de Wiart was in Somaliland. He was fighting the "Mad Mullah’s" forces. During an attack on a fort, he was shot in the face twice. He lost his left eye. He also lost a portion of his ear. This is where the famous black eyepatch comes from—it wasn't a fashion statement; it was a necessity. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for this, but he was mostly just annoyed that he had to go back to England to heal.

💡 You might also like: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

He actually hated the doctors.

When he finally got to the Western Front in 1915, things got even weirder. During the Second Battle of Ypres, his left hand was shattered by a shell. The story goes—and this is verified by multiple sources including his own autobiography, Happy Odyssey—that the doctor refused to amputate his fingers. So, Carton de Wiart bit them off himself. Later that year, the whole hand had to be removed anyway.

Leading from the Front at La Boisselle

Think about this for a second. He was a commander of the 8th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment. He had one eye and one hand. He was at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. During the fighting at La Boisselle, three other battalion commanders were killed. Carton de Wiart took over all of them. He was seen pulling the pins of grenades with his teeth and flinging them with his one good arm.

He won the Victoria Cross (VC) for that.

The VC is the highest military decoration in the British system. He didn't even mention it in the original draft of his memoirs. He was almost embarrassed by it, or maybe he just didn't think it was that big of a deal compared to the thrill of the fight itself. He was shot through the skull at the Somme. Then shot through the hip at Passchendaele. Then the leg at Cambrai. Then the ear at Arras. He just kept coming back.

The Interwar Years: Poland and the "Peace" Problem

Between 1919 and 1939, things got a bit more political, which he hated. He was sent to Poland as part of the British Military Mission. He survived a plane crash in the middle of it. He ended up living on a massive estate in the Pripet Marshes, which is basically a giant swamp. He spent fifteen years there, hunting and being a bit of a hermit.

📖 Related: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

He loved the Polish people because they were always fighting someone. It suited his temperament. He saw the Soviet invasion coming long before the politicians in London did. When the Nazis invaded in 1939, he had to make a run for it. He basically escaped through Romania on a fake passport, with the Gestapo trying to track him down.

World War II: The Old Man and the Sea (and the Prison)

He was in his 60s when World War II broke out. Most 60-year-olds are thinking about retirement. Adrian Carton de Wiart was thinking about how to get back into the thick of it. He was sent to Norway in 1940 to lead a force against the Germans. It was a disaster, but not because of him—the logistics were a mess. He managed to evacuate his troops while under constant air attack.

Then came the Mediterranean. In 1941, his plane crashed into the sea off the coast of Libya. He and the crew had to swim a mile to shore. He was captured by the Italians.

Escaping from Vincigliata

Being a high-ranking officer, he was sent to Castello di Vincigliata near Florence. He was sixty-one. He refused to sit still. He made five escape attempts. One of them involved him and several other officers digging a tunnel through solid rock for seven months.

He actually made it out.

He managed to evade capture for eight days, disguised as an Italian peasant. Keep in mind: he had one eye, one hand, couldn't speak Italian, and was covered in scars. It’s a miracle he lasted eight hours, let alone eight days. Eventually, he was recaptured, but the Italians were so impressed they eventually used him as a diplomat to help negotiate their surrender to the Allies.

👉 See also: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

Why We Still Talk About Him

There is a lot of "Alpha Male" nonsense on the internet today, but Adrian Carton de Wiart was the real deal without ever trying to sell a course on it. He was a complex man. He wasn't some bloodthirsty psychopath; he was just a man who found his absolute purpose in the chaos of combat.

- Physical Resilience: Medical science still looks at his records and wonders how he didn't die of infection in 1915.

- Mental Fortitude: He dealt with chronic pain his entire life without complaining.

- Leadership: His men followed him because he was always in the front trench, not five miles back in a chateau.

Critics sometimes argue that men like him glorified war. Maybe. But if you read his actual writing, he doesn't glorify the death; he glorifies the life he felt while he was in it. It’s a nuance that is often lost in modern history books. He was a relic of a different era, a Victorian soul trapped in the horrors of the 20th century, and he handled it by simply refusing to break.

Actionable Takeaways from a Remarkable Life

You don't have to go get shot in the face to learn something from Carton de Wiart. His life offers some pretty intense lessons on human capability.

- Adaptability is everything. When he lost his hand, he didn't retire. He learned to shoot, hunt, and fight with one hand. Don't let a change in circumstances end your "mission."

- Ignore the "Impossible" label. Most people told him he was too old for WWII. He went anyway. Most people told him he couldn't escape a mountain fortress. He dug a hole through it.

- Focus on the task, not the reward. He didn't brag about his Victoria Cross. He focused on the next battle. The accolades are a byproduct of the work, not the goal.

- Read the primary sources. If you want to understand him, find a copy of Happy Odyssey. It’s a masterclass in understated British stoicism.

Next time you think you’re having a rough day because the Wi-Fi is down or you have a headache, remember the guy who bit his own fingers off so he could get back to the front. It puts things in perspective. He died peacefully in his sleep at the age of 83 in County Cork, Ireland. After everything that tried to kill him—bullets, shells, planes, swamps—he went out on his own terms.

To really dig deeper into the military strategy of the era, you should look into the development of trench warfare during the 1916 campaigns. It explains why a single officer's bravery, like de Wiart's at the Somme, could actually change the outcome of a local engagement. You might also find it useful to research the British Military Mission to Poland in 1919, which is a frequently overlooked part of the post-WWI power struggle that de Wiart was right in the middle of.