He lost. Twice. And not just by a little bit, but in massive, electoral landslides that would have tucked most politicians away into a quiet corner of a law firm for the rest of their lives. Yet, somehow, Adlai Stevenson II remains this towering, almost ghostly figure in American liberalism. People still talk about him. They quote him. They wonder if he was "too smart" for the room, or if the room just wasn't ready for a guy who refused to talk down to it.

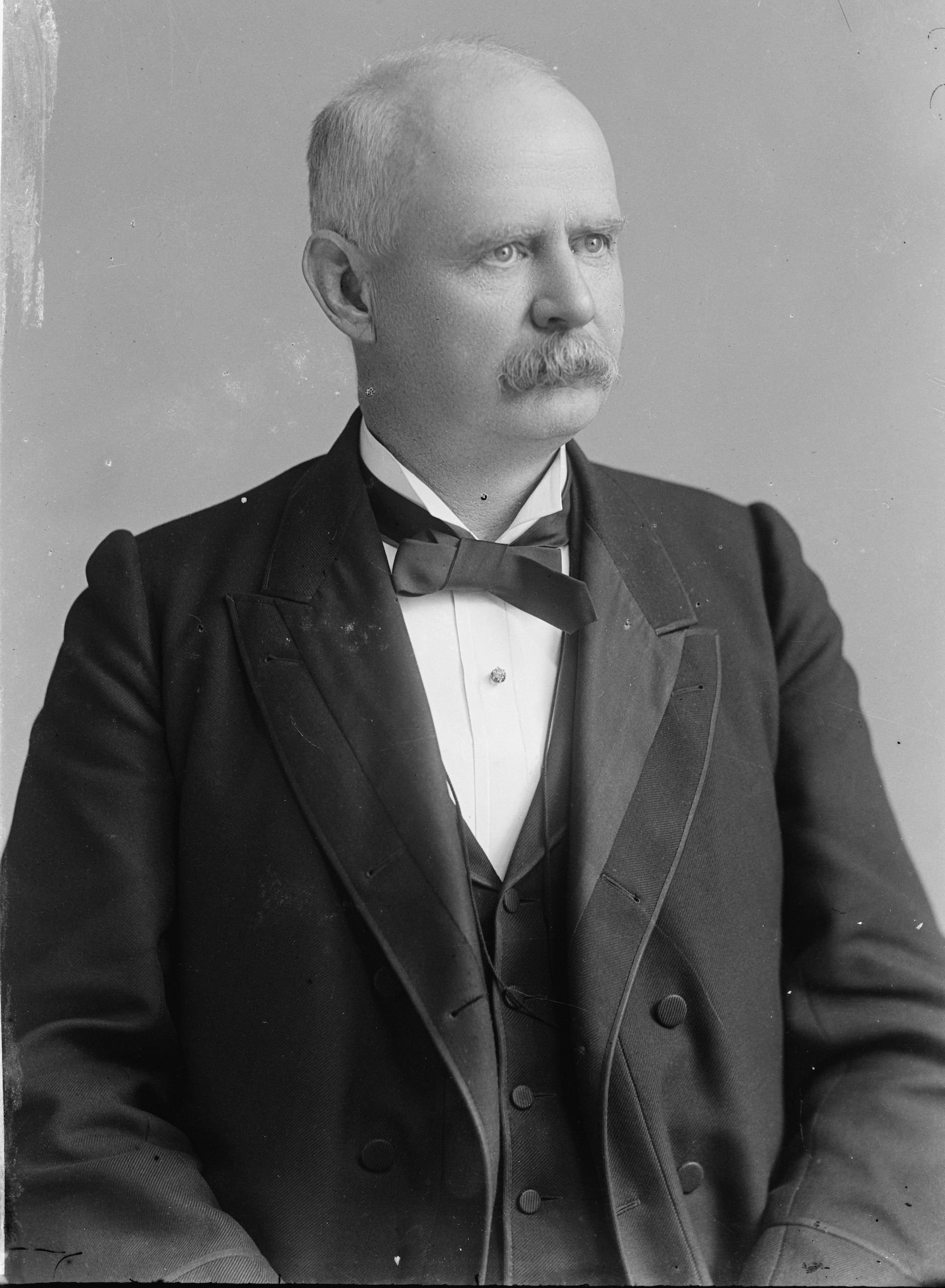

You've probably seen the grainy black-and-white footage. The high forehead, the slightly professorial squint, the elegant hands. He didn't look like a warrior. He looked like your favorite dean. But in 1952 and 1956, he was the only thing standing between the Democratic Party and total irrelevance during the Eisenhower era. He was a man of contradictions—a wealthy aristocrat from Illinois who became the darling of the working-class intellectual, a reluctant candidate who actually loved the spotlight, and a diplomat who could be devastatingly funny while discussing the end of the world.

Honestly, his story isn't just about losing. It's about how he changed the way we think about political language. Before Adlai, "egghead" was a slur. He turned it into a badge of honor. He basically taught a generation of Americans that being thoughtful wasn't a liability in public life.

The Governor Who Didn't Want the Big Job

It started in Illinois. Stevenson was a one-term governor who had actually done some pretty impressive stuff, like cleaning up the state police and fixing the schools. He wasn't looking for the White House. When Harry Truman approached him in early 1952 to run, Stevenson famously hesitated. He said no. Then he said maybe. Then he said no again.

This wasn't some calculated political ploy. He was genuinely worried he wasn't up for it, or maybe he just liked Springfield. But the 1952 Democratic National Convention in Chicago was a madhouse. Truman was out. The party was looking for a savior. Stevenson gave a welcoming speech that was so eloquent, so sharp, and so different from the usual political barking that the delegates basically drafted him on the spot.

"The sacrifice of spirits is better than the sacrifice of bulls," he told them. Who talks like that? Adlai did.

Why He Got Crushed by Ike

Let’s be real: nobody was beating Dwight D. Eisenhower in the fifties. Ike was the guy who won World War II. He was the nation’s grandfather. Stevenson, meanwhile, was the "intellectual."

💡 You might also like: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

The 1952 campaign was a bloodbath. Stevenson tried to talk about complex issues—foreign policy, civil rights, the nuance of the Cold War. Eisenhower’s team ran ads with a catchy jingle: "I Like Ike." It was the beginning of the "soundbite" era, and Stevenson hated it. He thought television was a "gimmick" that degraded the dignity of the office.

- He refused to use a teleprompter for a long time.

- He wrote his own speeches, often working on them until minutes before he went on air.

- He famously had a hole in the sole of his shoe, which became the iconic image of his campaign—the hard-working, "shabby-genteel" statesman.

In 1956, it was even worse. The economy was booming. People were buying suburban houses and station wagons. Why change horses? Stevenson lost 42 states. It was a staggering defeat. But here’s the weird part: his supporters didn't leave him. They became "Stevensonians." They were the precursor to the New Left, the volunteers who would later fuel the campaigns of JFK and Eugene McCarthy. He created a new kind of political activist—the suburban intellectual who cared about "ideas."

The Cuban Missile Crisis and the "Hell Freezes Over" Moment

If Stevenson had just been a two-time loser, we wouldn’t remember him. But then came 1962. John F. Kennedy, who had a complicated, somewhat frosty relationship with Stevenson, appointed him Ambassador to the United Nations.

Kennedy thought Stevenson was a bit soft. He called him "Ad-lay" with a hint of a smirk. But during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Stevenson became the face of American resolve.

On October 25, 1962, Stevenson faced off against Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin. The world was literally on the brink of nuclear war. Stevenson demanded to know if the Soviets had placed missiles in Cuba. Zorin stalled. He tried to act like he didn't hear the question. Stevenson didn't back down. He leaned in, his voice cracking with a mix of anger and authority.

"I am prepared to wait for my answer until hell freezes over!"

📖 Related: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

He then showed the world the U-2 spy plane photos of the missile sites. It was one of the most dramatic moments in the history of the UN. It proved that the "egghead" had teeth. He wasn't just a man of words; he was a man who understood the weight of global survival. It’s one of the few times in history where a UN debate actually felt like the most important thing happening on the planet.

The Misconception of the "Indecisive" Man

History books often paint Stevenson as "Hamlet-like"—incapable of making a decision, forever brooding over the "to be or not to be" of a political run. That’s a bit of a caricature.

While it’s true he agonized over the presidency, he was incredibly decisive on things that mattered. He was an early advocate for a nuclear test ban treaty, something that was considered "radical" or "weak" at the time. He pushed for civil rights long before it was politically safe for a national Democrat to do so with full vigor. He was a globalist who believed that the United Nations was the only thing keeping the human race from self-destruction.

He wasn't indecisive; he was just aware of the consequences. He understood that the world wasn't a comic book. There weren't easy answers. To Stevenson, being a "leader" meant acknowledging the complexity of a problem, not ignoring it for the sake of a campaign slogan.

The Wit of Adlai Stevenson II

We don't get funny politicians anymore. Not really. We get scripted jokes and practiced zingers. Stevenson was actually, genuinely witty in a way that felt spontaneous.

When a woman once shouted at him, "Senator, you have the vote of every thinking person!" he reportedly shouted back, "That’s not enough, madam, we need a majority!"

👉 See also: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

He knew he was out of step with the times. He knew he was a "highbrow" in a "lowbrow" era. But he leaned into it. He once defined an editor as "someone who separates the wheat from the chaff and then prints the chaff." He had this self-deprecating charm that made it impossible to truly hate him, even if you disagreed with his tax policy.

Why His Legacy Still Haunts the Democratic Party

Every time a "smart" candidate runs for president—think Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, or even Pete Buttigieg—the ghost of Adlai Stevenson II is in the room. There is a persistent fear in American politics that being "too articulate" makes you "elitist."

Stevenson was the first victim of the "beer test." Could you see yourself having a beer with him? Probably not. You’d probably see yourself having a glass of dry sherry with him while discussing the Marshall Plan. And for a huge chunk of the American electorate, that was a problem.

But he left a blueprint. He showed that you could lose and still lead. He professionalized the "policy wonk." He made it okay for politicians to be authors and thinkers. Without Stevenson, the intellectual infrastructure of the modern Democratic party wouldn't exist. He brought the academics out of the universities and into the smoke-filled rooms of the 1950s.

How to Apply the Stevenson Legacy Today

If you're looking for lessons from the life of Adlai Stevenson II, it isn't "how to win an election." He was objectively bad at that. The lessons are about how to conduct yourself when the stakes are high and the world is watching.

- Prioritize Substance Over Soundbites. Stevenson believed that the American people were capable of understanding complex truths. While he lost the elections, his ideas on nuclear arms control and international cooperation eventually became the standard. If you're communicating a difficult idea, don't dumb it down. Respect your audience enough to be thorough.

- Accept Grace in Defeat. His concession speeches are masterpieces of American prose. In 1952, he quoted Abraham Lincoln, saying he was "too old to cry, and it hurt too much to laugh." How you lose often defines your character more than how you win.

- The Power of Moral Courage. Standing up to the Soviets at the UN wasn't just about the photos; it was about the refusal to let a lie stand in the way of global safety. In your own professional or personal life, identify the "Zorin moments" where silence is complicity.

- Be the "Egghead." Don't apologize for being informed. In a world of snap judgments and 280-character arguments, there is a massive, underserved market for depth and nuance. Stevenson proved that even if you don't get the "majority," you can still shape the narrative for decades.

Adlai Stevenson II died on a sidewalk in London in 1965, still serving his country at the UN. He never got the big house on Pennsylvania Avenue. But if you look at the way we debate foreign policy or the way we value intellectual rigour in our leaders, his fingerprints are everywhere. He was the most successful "loser" in American history because he refused to win by becoming someone he wasn't.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To truly grasp the Stevenson era, read his 1952 welcoming speech at the DNC; it remains one of the finest examples of political oratory. You should also watch the archival footage of the 1962 UN Security Council meeting on the Cuban Missile Crisis to see the "Hell Freezes Over" moment in its original context. Finally, look into the "Stevensonians"—the grassroots volunteers of 1952—to understand how he fundamentally restructured political campaigning for the modern age.