When people talk about the Brad Pitt space movie, they usually expect Star Wars. Or maybe Interstellar. They want dogfights in a vacuum or high-stakes physics puzzles that save the human race from a dying Earth. But James Gray’s Ad Astra isn't really that. Honestly, it’s more of a moody, psychological therapy session that just happens to take place on the way to Neptune.

It’s polarizing.

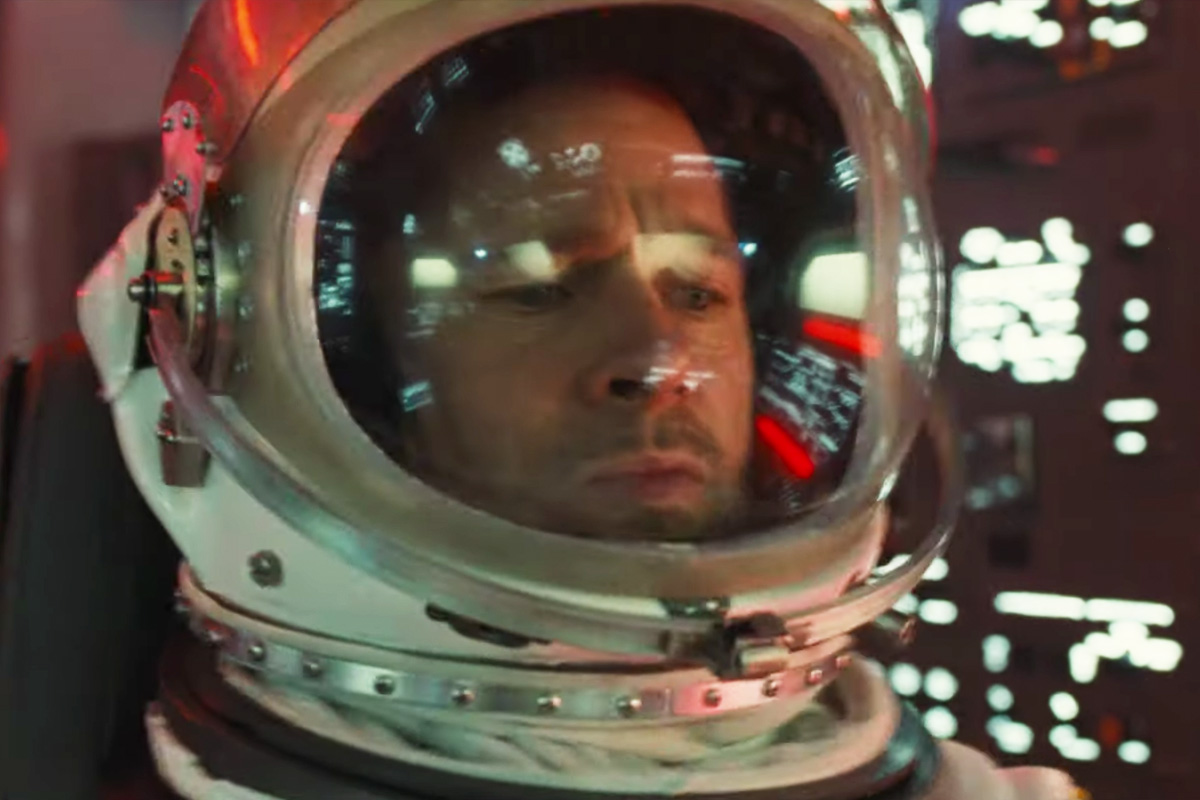

Released in 2019, the film follows Major Roy McBride—played by Pitt with a stillness that is almost unnerving—as he travels across a decaying solar system to find his father. If you went into the theater looking for an adrenaline rush, you probably walked out feeling confused. If you went in looking for a meditation on toxic masculinity and the terrifying silence of God, you found a masterpiece.

Why Ad Astra is the Most Realistic (and Depressing) Vision of the Future

Most sci-fi treats space travel like a glamorous adventure. Ad Astra treats it like a flight through Newark Liberty International Airport.

Everything is beige. Everything is corporate. When Roy lands on the Moon, he doesn't find a shining utopia; he finds a DHL kiosk and an Applebee’s. It is the ultimate critique of human expansion. We didn't go to the stars to be better; we went to the stars to bring our strip malls with us. This groundedness is what makes this Brad Pitt space movie stand out from the pack.

The physics, for the most part, actually try.

While the "Space Antenna" fall in the opening sequence is a bit of a stretch for cinematic tension, the way the film handles silence is incredible. Sound doesn't travel in a vacuum. Most movies cheat this because it's "boring." Gray doubles down on it. When pirates attack the lunar rovers—yes, Moon pirates are a real thing in this movie—the lack of explosive sound makes the scene feel ten times more violent. It’s clinical. It’s cold.

The Problem With Roy McBride

Roy is a man whose pulse never goes above 80. Even when he’s falling from the edge of space, he’s calm.

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

Is he a hero? Or is he just broken?

The movie argues the latter. He’s a victim of his father’s legacy. Tommy Lee Jones plays H. Clifford McBride, a man who became so obsessed with finding alien life that he forgot how to be a human being. He’s the "Great Explorer" who turned out to be a monster. We see this play out in Roy’s internal monologue—a device that many critics hated, comparing it to a diet version of Apocalypse Now. But the voiceover is essential. Without it, Roy is just a blank slate. With it, we realize he’s a man who is terrified that he’s becoming his father.

The Technical Brilliance Nobody Talks About

We need to talk about Hoyte van Hoytema.

He’s the cinematographer who also shot Interstellar and Oppenheimer. The guy knows how to make big things look small and small things look infinite. In this Brad Pitt space movie, he uses a specific color palette to signal Roy’s mental state. Earth is lush. The Moon is a sterile, washed-out grey. Mars is a claustrophobic, pulsating red. By the time Roy reaches Neptune, the film is bathed in an eerie, deep blue.

It feels like drowning.

The production design, led by Kevin Thompson, avoids the "used universe" look of Alien but also rejects the pristine white of 2001: A Space Odyssey. It feels functional. It feels like something a government contractor would build. That realism is why the movie has aged so well despite its lukewarm box office performance. It doesn't feel like a "movie" version of 2050. It feels like 2050.

Breaking Down the "Space Monkey" Scene

Everyone remembers the monkeys.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Halfway to Mars, Roy’s ship responds to a distress call from a biomedical research station. They find baboons. Angry, carnivorous, zero-G baboons. It’s the weirdest scene in the movie. Some people think it ruins the tone. I’d argue it’s the most important metaphor in the script.

The monkeys are us.

They are creatures plucked out of their natural habitat, driven mad by the isolation of space, and turning on each other. It’s a warning. If we go to Neptune without fixing our own heads, we’re just the monkeys in the station. We’re just violent animals in a high-tech cage. Pitt’s reaction to the attack is telling—he kills the threat, cleans himself off, and checks his heart rate. He is more machine than man at that point.

What Ad Astra Says About the Search for Life

The central mystery of this Brad Pitt space movie is the "Lima Project." Roy’s father was sent out to find "The Others." He never found them.

The film's "twist"—if you can call it that—is that there is nothing out there.

That’s the part that hurts.

Usually, in movies like Contact or Arrival, we get a handshake from a grey alien or a tesseract behind a bookshelf. Ad Astra looks into the abyss and tells us that we are completely, utterly alone. For Clifford McBride, that realization was a death sentence. He couldn't handle a universe where he was the only thing looking back. For Roy, it’s a liberation.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

If there is nothing out there, then what we have here matters.

Practical Insights for Your Next Rewatch

If you’re going back to watch Ad Astra after reading this, keep a few things in mind to get the most out of the experience.

- Watch the eyes. Brad Pitt’s performance is almost entirely in his pupils. Watch how he reacts when he has to record the message to his father on Mars. The facade cracks for exactly three seconds.

- Focus on the sound design. Use headphones or a decent soundbar. The subtle hum of the ships and the muffled "thuds" during the rover chase are intentional.

- Forget the science for a second. Yes, jumping through Neptune’s rings with a piece of sheet metal is physically impossible. Don't let that ruin the poetic intent. It’s a movie about a son reaching for a father, not a NASA training video.

- Compare it to The Lost City of Z. James Gray made that movie right before this one. It’s the same story—a man loses himself in the jungle looking for a myth. Ad Astra is just The Lost City of Z in a vacuum.

The legacy of this film isn't going to be its box office numbers. It’s going to be the way it captured a specific kind of 21st-century loneliness. We have all the technology in the world to connect us, yet we've never felt further apart. Roy McBride has to go to the edge of the solar system just to realize he should have stayed home and grabbed coffee with his wife.

It’s a long way to go for a simple lesson, but sometimes the vastness of space is the only mirror big enough to see ourselves clearly.

If you want to dive deeper into the genre, look at how Ad Astra bridges the gap between the hard sci-fi of the 70s and the modern "prestige" sci-fi movement. It rejects the "Hero's Journey" in favor of a "Healer's Journey." Roy doesn't kill the dragon; he realizes the dragon was a sad, lonely old man and decides he doesn't want to be one too.

To truly appreciate the film, research the concept of the "Overview Effect." It’s a real cognitive shift experienced by astronauts when seeing Earth from space—a feeling of intense protection and connection to the planet. Roy experiences the inverse: he sees the void and realizes that the only thing that makes the void bearable is the people we leave behind.

Stop looking for aliens. Start looking at the person sitting next to you. That’s the real takeaway from the Brad Pitt space movie.

Actionable Next Steps

- Screening: Watch the 4K UHD version if possible. The HDR mastering on the Neptune sequences is some of the best in the format's history.

- Reading: Check out Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad. It is the primary literary influence for the film’s structure and Roy's descent into madness.

- Comparison: Watch Solaris (either the Tarkovsky version or the Soderbergh remake). It provides a similar take on how space acts as a catalyst for human grief.

- Soundtrack: Listen to Max Richter’s score on its own. It’s a masterclass in minimalist ambient music that captures the "coldness" of the film's setting.