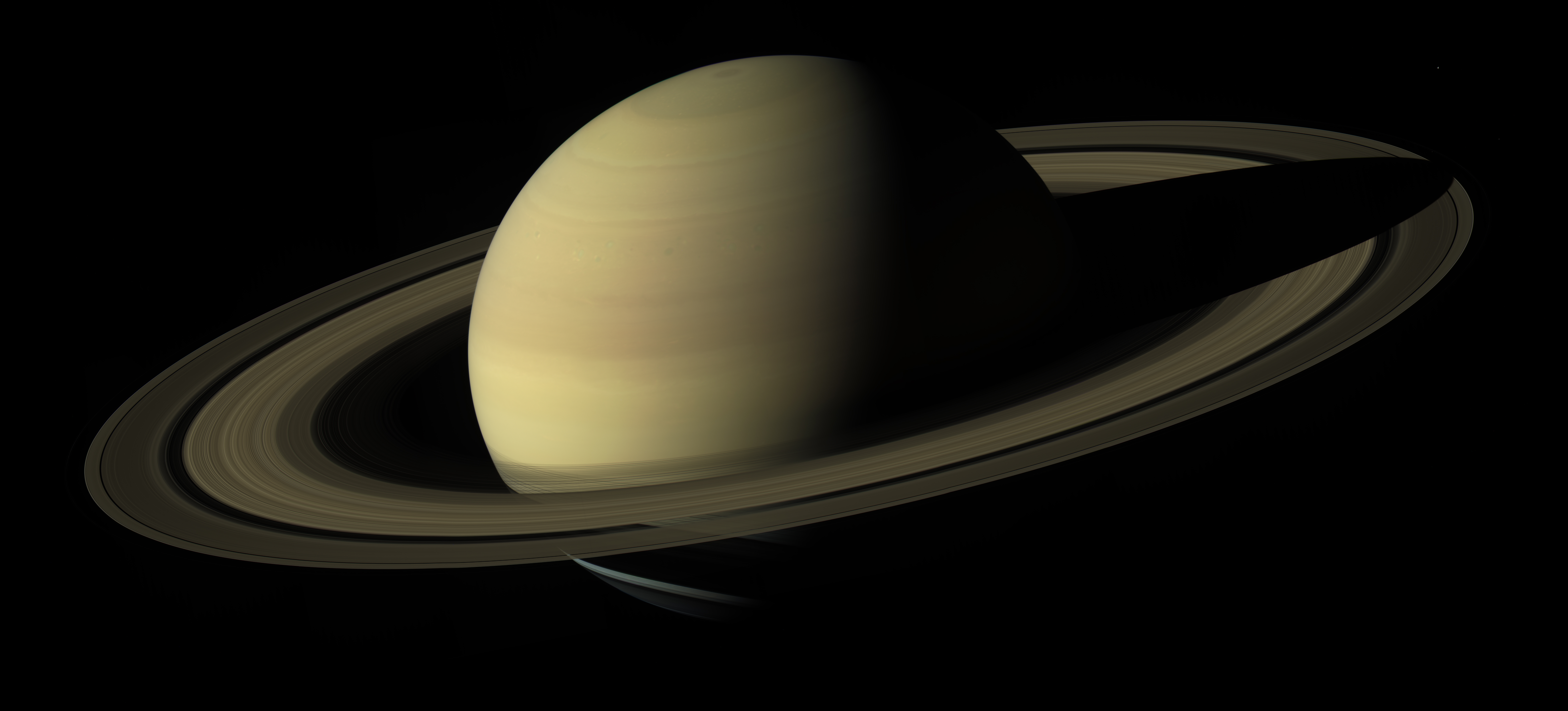

You’ve seen the posters. Those glowing, neon-purple rings and hyper-saturated gas clouds that look like something out of a 1970s synth-wave album cover. They're gorgeous. But honestly? Most of them aren't "real." When people go looking for actual pictures of Saturn, they usually end up staring at artist's impressions or "false-color" composites that make the planet look a lot more dramatic than it would if you were hanging out the window of a spacecraft.

Saturn is actually quite beige. It’s a muted, butterscotch-colored world.

If you were to fly a ship to the sixth planet, your eyes wouldn't see the electric blues and deep magentas popularized by Instagram infographics. You'd see a giant, hazy ball of hydrogen and helium with subtle, tan-colored bands. This isn't to say the planet is boring. Far from it. The reality of what we’ve captured with cameras like those on Cassini and Voyager is arguably more mind-bending because those pixels represent physical objects—trillions of ice chunks—floating in a perfect disk around a world 700 times larger than Earth.

The Cassini Legacy and Raw Data

Between 2004 and 2017, the Cassini-Huygens mission changed everything. Before Cassini, our actual pictures of Saturn were mostly grainy shots from the Voyager flybys or distant, blurry captures from the Hubble Space Telescope. Cassini spent over a decade orbiting the gas giant, and it sent back over 450,000 images.

Here is where it gets technical. Most of the cameras we send into space don't take "color photos" the way your iPhone does. They use monochrome sensors with a series of filters. To get a "true color" image, scientists have to take three separate exposures—one through a red filter, one through green, and one through blue—and then stack them. If a moon moves during those exposures, you get a weird rainbow "ghost" effect on the edges.

Cassini's Wide Angle Camera (WAC) and Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) weren't just taking snaps for postcards. They were measuring light intensity at specific wavelengths. When NASA releases a photo, they often use "natural color" to show what a human would see, but they also release "false color" versions. Why? Because those neon greens and reds help researchers distinguish between different altitudes of clouds or chemical compositions in the atmosphere. Methane looks different than ammonia in infrared, but to your eye, it’s all just... tan.

✨ Don't miss: Gmail Users Warned of Highly Sophisticated AI-Powered Phishing Attacks: What’s Actually Happening

What Actual Pictures of Saturn Reveal About the Rings

The rings aren't solid. You probably know that, but seeing the high-resolution photos makes it hit differently. They are 99.9% pure water ice.

In the most detailed actual pictures of Saturn taken during Cassini’s "Grand Finale" orbits, we can see "propellers." These are tiny wakes created by small moonlets embedded within the rings. The rings are incredibly thin—sometimes only 30 feet thick—but they span 175,000 miles. Think about that. If you had a piece of paper the size of a football field, it would still be proportionally thicker than Saturn's rings.

One of the most famous photos, titled "The Day the Earth Smiled," shows Saturn eclipsing the sun. In the far distance, there’s a tiny blue speck. That’s us. That’s Earth. Seeing our entire civilization reduced to a single pixel behind the translucent glow of the E-ring is a perspective shift that no CGI render can replicate.

The Hexagon at the North Pole

Perhaps the weirdest thing ever captured in actual pictures of Saturn is the North Pole Hexagon. It sounds fake. It looks like someone photoshopped a geometric shape onto a planet. But it’s a real, persistent cloud pattern.

First spotted by Voyager and later confirmed in high definition by Cassini, this six-sided jet stream is about 20,000 miles wide. You could fit two Earths inside it. It’s not caused by aliens or some secret base; it’s fluid dynamics on a massive scale. Scientists like Dr. Kevin Baines from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory have explained that when you have different wind speeds at different latitudes, the "shear" creates these polygonal shapes. It’s basically a massive, permanent hurricane that refuses to be round.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Apple Store Naples Florida USA: Waterside Shops or Bust

The color of the hexagon actually changed between 2012 and 2016. It went from a bluish hue to a golden yellow. This happened because of the change in Saturn’s seasons (which last about seven Earth years each). As the north pole tilted toward the sun, increased sunlight produced more "photochemical haze," shifting the color. Seeing those chronological actual pictures of Saturn side-by-side is how we actually track the planet’s climate.

Why Hubble Pictures Look Different

We still get "new" photos of Saturn even though Cassini is long gone (it was intentionally crashed into the planet in 2017 to protect the moons from contamination). The Hubble Space Telescope takes an annual "portrait" of the planet as part of the Outer Planets Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) program.

Hubble photos look crisp and vibrant, but they lack the "close-up" grit of Cassini. From Earth's orbit, Hubble sees the whole disk. In these actual pictures of Saturn, you can see the rings "tilting." Because Saturn has an axial tilt similar to Earth, we see the rings from different angles over its 29-year orbit. Right now, the rings are appearing to "close" from our perspective. By 2025 and 2026, they will appear as a razor-thin line, making them almost invisible from Earth-based telescopes. It’s a phenomenon called a ring plane crossing.

Spotting the Fakes and Enhancements

If you see a photo where Saturn looks like it’s glowing from inside, or where the rings are neon orange, it’s likely an "artist’s concept" or a heavily processed infrared composite.

- Check the source. NASA’s Photojournal or the ESA (European Space Agency) archives are the only places for raw data.

- Look at the stars. Actual cameras exposed for Saturn’s brightness usually can’t see stars in the background. If the background is full of twinkling constellations, it’s probably a composite or CGI. Saturn is very bright; to get a good exposure of the planet, the faint light of distant stars is usually lost.

- Shadows are key. In actual pictures of Saturn, the planet casts a massive shadow onto its own rings. This shadow is sharp and black. In many fake or low-quality renders, people forget how light works in a vacuum and the shadow looks soft or is missing entirely.

Exploring the Moons Through Saturn's Lens

We can't talk about images of the planet without mentioning its companions. Enceladus and Titan are the stars here.

💡 You might also like: The Truth About Every Casio Piano Keyboard 88 Keys: Why Pros Actually Use Them

Cassini captured actual pictures of Saturn where Enceladus, a tiny ice moon, is silhouetted against the planet. These photos showed plumes of water vapor shooting out of the moon's south pole. This wasn't just a cool photo; it was proof of a subsurface ocean. Then there’s Titan. Most pictures of Titan just show an orange ball of smog. But by using infrared sensors, Cassini peered through the clouds to see liquid methane lakes.

The most "human" photo we have from this region isn't even of Saturn itself, but from the surface of Titan. The Huygens probe landed there in 2005 and sent back a single, grainy photo of rounded "rocks" (which are actually chunks of water ice) on a dark, orange plain. It remains the most distant landing ever achieved by humanity.

How to Find Raw Images Yourself

If you want to see the real deal without any PR polish, you can go to the PDS (Planetary Data System) archives. These are the "raw" files. They are often black and white, full of "noise" or static from cosmic rays hitting the sensor, and sometimes they look totally overexposed.

Amateur image processors take these raw files and turn them into masterpieces. People like Kevin Gill or Jason Major spend hours calibrating these data sets to create the breathtaking actual pictures of Saturn you see on science news sites. They aren't "faking" them; they are translating raw digital numbers into colors that make sense to our brains.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the visual reality of the ringed planet, stop looking at "top 10" listicles and go to the source.

- Visit the NASA Cassini Photojournal: Search for "PIA" numbers (NASA's indexing system). PIA17172, for example, is the famous "Day the Earth Smiled" high-res composite.

- Follow Citizen Scientists: Look up "amateur image processing" on forums like https://www.google.com/search?q=UnmannedSpaceflight.com. These enthusiasts often produce better "true color" renders than the official press releases.

- Check the Planetary Society: They maintain a massive database of raw mission data that is much more user-friendly than the official government archives.

- Use a Backyard Telescope: If you have even a basic 4-inch telescope, you can see the rings yourself. It won't look like a Hubble photo—it will be a tiny, cream-colored marble—but seeing the "actual" photons hitting your eye is a completely different experience than looking at a screen.

Saturn is currently moving toward its equinox. This means the sun will hit the rings edge-on, creating long, dramatic shadows from the "peaks" of the rings (vertical structures caused by moon gravity). These images, captured years ago and still being analyzed, continue to prove that the reality of the solar system is far more interesting than any filter-heavy render could ever be.

Next Steps for Deep Research

To see the planet in its most honest form, head to the NASA Solar System Exploration website and filter by the "Cassini" mission. Look for images labeled "Natural Color." You will notice the subtle gradients of gold and grey that define the atmosphere. If you're interested in the technical side, search for "Cassini ISS (Imaging Science Subsystem) calibration papers" to understand exactly how those photons were converted into the digital images we see today. Keep an eye on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) feeds as well; its infrared views of Saturn are currently revealing atmospheric details that were invisible even to Cassini, specifically regarding the temperature of the ring system and the deep cloud layers.